A new US strategy in the fight against so-called Islamic State?

- Published

More US troops are backing up the groups fighting so-called Islamic State

A little under a week ago the new US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson met his counterparts from a variety of countries and organisations which make up the wide-ranging coalition set against so-called Islamic State (IS). He told them that defeating IS remained Washington's "number one goal in the region".

But three months into the Trump administration, and in the wake of a full-scale review of the strategy deployed against IS, it is hard to see a substantial difference between the new president's approach and that of his predecessor, Barack Obama. Rather, the most significant shift may be that Mr Trump is applying the Obama recipe with more punch, more resources and greater flexibility.

'Obama Plus'

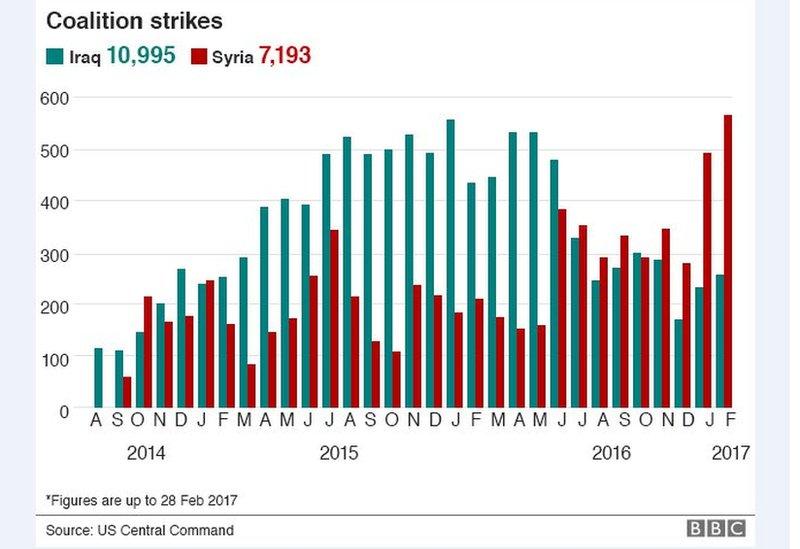

Additional US troops and fire-power have been despatched to Syria, and US forces have taken a much greater part in facilitating the operations of their allies.

A good example of the Trump administration's "Obama Plus" approach was the recent air assault on the Tabqa dam, part of the effort to cut off and isolate Raqqa. Here, the US flew in hundreds of anti-IS fighters and supported the operation with US Army apache helicopter gunships, along with artillery fire from the US Marines, as well as conventional air power.

More generally, US advisers seem to be closer to the front line - drone strikes against militant leaders are more active than ever across the region, and some 2,500 additional troops from the 82nd Airborne Division are being staged to Kuwait to provide, in effect, an operational reserve that could be deployed at short-notice to either Syria or Iraq.

All the signs are that military commanders are being given greater autonomy in pushing forward the operation, whether it be freeing up the Pentagon from the micro-management of the White House and National Security Council, or greater leeway to local US commanders in Iraq to call in air strikes.

Inevitably, this has led to problems.

Reports suggest the civilian death toll is growing markedly, although it is not clear if this is due to strikes hitting the wrong targets - because of the increasing tempo of the operations - or because this final phase of the Mosul battle, in a populated built-up area, was inevitably going to be more brutal.

US spokesmen insist there have been no recent changes in operational procedures for approving airstrikes - although Iraqi officials suggest otherwise.

A US coalition spokesman has acknowledged "delegated approval authority for certain strikes" has been given "to battlefield commanders to provide better responsiveness to the Iraqi Security Forces when and where they needed it on the battlefield".

Read more:

US forces are now much more intimately involved in the fighting in both Iraq and Syria, though there are still the ritual denials that they are actually in the front line.

US forces are heavily engaged in logistical and combat support, as well as in the training effort. So on the military front at least, the Obama Plus approach seems to be paying off. The final battle for Mosul will be unpleasant - so too will that for Raqqa when it is finally joined. But there is little doubt that IS will suffer a grave setback with the eventual loss of both cities and the collapse of its so-called caliphate.

But what of the overall regional strategy guiding the operation? Or more to the point is there one? The Trump administration has so far shown little original thinking. Here too it seems to be broadly following the approach of its predecessor.

Reports suggest civilian deaths have increased in Mosul

One difference is that the Obama administration was dead set against establishing safe zones in Syria. In contrast, Secretary of State Tillerson has spoken in vague terms about "interim zones of stability", perhaps in the border areas near Turkey and Jordan. But since Turkish troops and their Syrian allies already occupy a significant swathe of Syrian territory, this may well be an issue decided more by Ankara than by Washington.

What is lacking, just as it was under Mr Obama, is any clear and comprehensive strategy for the future of Syria and, indeed, Iraq. So many questions remain unanswered:

Who will hold onto the territory liberated from IS in Syria?

How will Washington choose between the competing demands of its Kurdish and Turkish allies?

How can the growing influence of Iran in both Syria and Turkey be contained?

What are the risks of stepping up support for the Saudi-led coalition fighting in Yemen?

How can the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad be made more acceptable to its Sunni citizens?

What regional understanding, if any, can Washington have with Moscow (the much heralded re-set between the two major powers being one of the first casualties of the Trump administration's controversial birth-pangs)?

This struggle, of course, is not just a military and diplomatic one. It also has a crucial ideological dimension - mobilising Muslim hearts and minds against the poisonous ideas of IS. Here too there have been early stumbles by the Trump administration. Its travel bans and security measures directed largely at the Muslim world have been poorly explained, and of questionable legality.

It is early days yet, but global conflict makes no concessions to the steep learning curve required for any new US administration. That is also what makes the Trump team's slowness in making key appointments so worrying. The US seems to be intensifying its military campaign against IS without any real equivalent diplomatic surge.

- Published10 July 2017

- Published22 March 2017

- Published25 March 2017

- Published9 March 2017