Is so-called Islamic State finished?

- Published

Under fire from Russian, Turkish, Iraqi, Syrian and Kurdish forces, as well as US air power, so-called Islamic State has lost large swathes of land, as well as fighters and money. What does this mean for the Islamist militant group? Is it finished?

On 13 August this year, the town of Manbij in northern Syria was liberated from IS. After the last fighter left, the town erupted: men sat on street corners, cutting off each other's beards; women tore off their face veils and set fire to them; an old woman lit a cigarette and laughed through the smoke.

Previously, all of this was banned by IS.

IS has lost other towns too, such as Kobane, al-Qaryatain, Tikrit and Fallujah.

A woman smoking in Manbij after it was liberated from IS control

But how much land has it lost in total? The risk consultancy group IHS produces maps to show which areas IS currently controls. It says that the amount of territory that IS has lost depends on how you are measuring.

"If you include the desert," says senior principal analyst Firas Abi Ali, "then it's lost around half of what it controlled a few years ago."

But it is perhaps more instructive to look at which cities it has lost. In losing towns such as Manbij, it has lost access to the Turkish border, which means the supply of foreign fighters, weapons and ammunition is drying up.

Losing cities means losing money too.

"When you control land and people, you gain access to revenue," says Firas Abi Ali. "You can extort the population. As it loses territory, it loses access to that pile of cash and it has less money available."

Firas Abi Ali estimates IS has lost about one-third of its capability to make money and predicts that the group will be defeated militarily by late 2017.

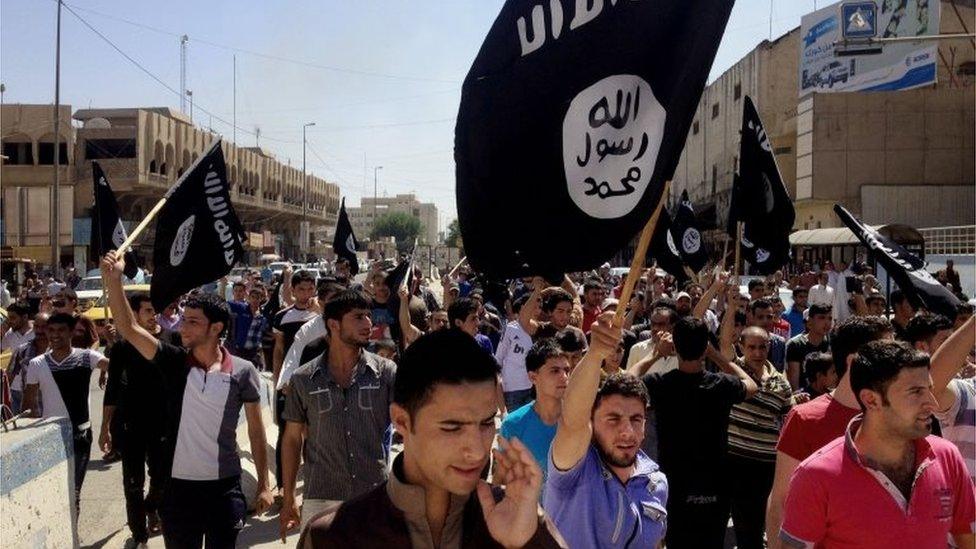

The big question now is whether IS can win back some of these cities, and the answer to that is partly about support.

Hassan Hassan's hometown in Syria was taken over by IS a few years ago, and he is now an analyst at the Tahrir Institute in Washington DC.

Over the past few years, he has been talking regularly to IS fighters online, and he says he has noticed something new.

"They're certainly worried," he says. "You get a sense that many people have lost the morale and the zeal that they had in 2014 when they joined because it was a 'caliphate' and it was expanding."

Now that the "caliphate" is shrinking, thousands of fighters are leaving. Along with those killed in battle, Hassan Hassan thinks IS has lost about half those who once fought for it.

Then there are those who did not fight for IS but supported or at least tolerated the group - not many, but enough to make it easier for IS to conquer so many towns. That is now changing too.

"People inside Syria and Iraq, they didn't understand [IS] in the beginning," he says. "They understand it today. People no longer talk about [IS] in the same way they talked about it in 2014."

IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi emerged from the shadows, appearing in Mosul in June 2014

IS itself seems to be accepting its new, weaker position. In its Arabic newsletter, the Dabiq, it is now talking about retreat. "They've started preparing their fighters psychologically for the retreat into the desert," says Hassan Hassan. "They're showing videos of IS members fighting in the desert, and these videos are new."

There are questions too about what this loss of land, fighters and money means for IS's ability to launch attacks.

Seth Jones, director of the International Security and Defense Policy Center at Rand Corporation think tank, has been studying IS documents found by Iraqi and US forces in Syria and Iraq.

"Islamic State is moving from an organisation that controls large amounts of territory into a terrorist group that is striking targets," he says.

In 2014, he says, every month there were about 150 to 200 attacks. In some months of 2016, there have been almost 400 attacks.

"They're trying to encourage people who believe the organisation is declining to continue to fight," he says. "To show that they still exist and they're still targeting 'the infidel'."

Other IS documents make it clear, he says, that the group wants to attack those countries involved in operations against it; such as the US, the UK and Australia. But with reduced finances, it will struggle to do so.

So-called Islamic State was formed in defiance of the al-Qaeda leadership

Increasingly, then, IS is relying on inspiring people to carry out attacks in its name, which means its leaders do not have to mastermind complex plots. IS is branching out too: into Nigeria, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Algeria and Egypt, as well as parts of Europe. But there, too, it is under threat.

This raises a question: how long can IS keep inspiring attacks and spreading its ideology? Will there come a time when it runs out of steam?

"At some point those attacks will likely come down as the group begins to lose more broadly," says Seth Jones. "It's unclear when that will be for IS. I don't think it's there yet, but it's certainly possible in the near- to mid-term."

Many experts think it is now just a matter of time before IS loses its most important cities: Mosul in Iraq and Raqqa in Syria. If that happens, what then?

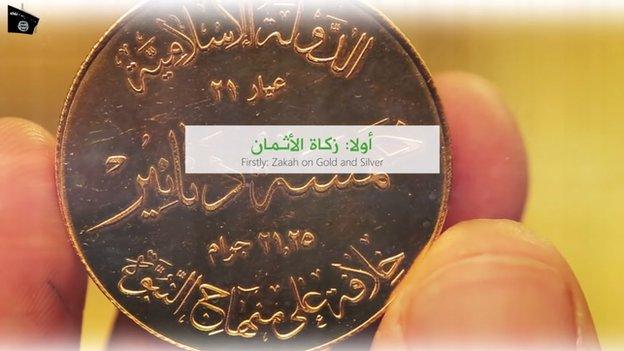

IS previously showcased coins it had minted for its "caliphate"

"Even if the territorial caliphate in Iraq and Syria is dismantled, this doesn't mean the end of the movement," says Fawaz Gerges, author of ISIS: A history.

Although IS shares some of its ideology with other militant groups, such as al-Qaeda, it differs in one key respect: it did not just talk about a caliphate; it conquered cities, erased borders and declared one. And in doing so, says Fawaz Gerges, it has energised global jihadism.

"The caliphate model will likely haunt the imagination of jihadists for many years to come," he says.

So where does all of this leave IS?

A year ago, no-one predicted IS would lose so much so quickly. And as it loses more land in the coming months, it is likely to lose more fighters. After all, what is Islamic State without a state?

So is Islamic State finished? Yes, it will lose its caliphate. But then the insurgency will begin.

The Inquiry: Is Islamic State finished? is broadcast on the BBC World Service. Listen online or download the programme podcast.