Saving Mosul's mothers-to-be

- Published

Many of the civilians fleeing their homes in Iraq are women with children (Stock picture)

The US has withdrawn $32.5m (£26m) in funding for the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), an agency that promotes family planning in more than 150 countries.

The state department believes the UNFPA "supports or participates in" coercive abortion programmes.

But the agency says all of its work protects the rights of individuals and couples to make their own decisions, free of discrimination.

Some of their most important projects help women give birth safely in war zones like IS-occupied Mosul, where maternity care has been crippled.

Muna is in her late 20s, with six children aged under 11. On the night she fled IS-held Mosul, she was just three days off giving birth to the latest - a baby boy she named Najm (Star).

Under cover of darkness, her large, frightened family escaped along with their neighbours, who had heard about a safe route out of the city.

They took only basic supplies. Determined that her child would not be born under IS rule, Muna ran from her home, abandoning her possessions and the family livelihood - her husband's shop.

She's far from alone. Iraq has one of the highest fertility rates in the world, with an average of four births for every woman.

Of the roughly 300,000 people displaced in Mosul by April 2017, between 9,000 and 12,000 would have been pregnant.

Without drugs or doctors they risk dying in childbirth along the way, as well as the hazards facing all escapees: Being shot, blown up by landmines, or captured and tortured by IS thugs. Unsurprisingly, miscarriages are common.

Their best hope comes from humanitarian groups in the area - notably the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), which works to help pregnant women caught in emergencies.

Ramanathan Balakrishnan, the UNFPA Representative for Iraq, told the BBC there are four mobile clinics serving Mosul which follow those fleeing the district, bringing qualified medics and a safe environment to those in need.

"Whether women are on the move or not, the need for obstetric care doesn't go away. So wherever women are going, they go."

The UNFPA medical team tend a baby born in their delivery room

Muna's escape route took her to Qayyara, a town 60km (37 miles) from Mosul on the banks of the Tigris River.

Considered a strategic centre, it was reclaimed from IS by Iraqi forces in August 2016 - but its childcare facilities are parlous. As of February 2017, the UNFPA delivery room there had brought 487 babies into the world.

Asked about her tiny son's future, Muna replies: "I hope he will become a doctor to heal people."

Huda, who is in her mid-20s and delivered her baby daughter three weeks after fleeing IS, says the same.

"I have three children - a boy and two girls. I know that they will make me a very proud mother," she smiles.

The young family fled from a village near Qayyara.

"The idea of escaping IS had been discussed several times among us, but we were always too afraid to do it because of the stories we heard about people who got killed or tortured while trying to escape," she says.

Huda says she was famous locally for her delicious fresh bread, which she would sell to her neighbours.

As IS gripped the area and the daily atrocities multiplied, one of those neighbouring families was forced from their home - the building seized for use as "storage".

When they refused to leave, the militants threatened to blow it up.

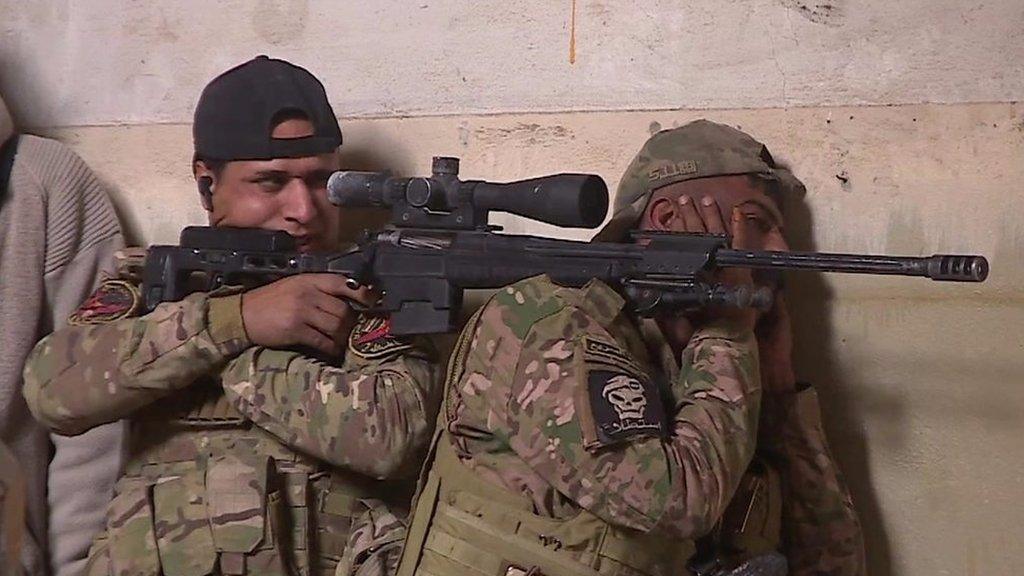

Mosul has been ravaged as Iraqi forces and IS militants battle for control of its streets

One of her brothers chose the day of their deliverance, arranging for Huda to flee with her mother and husband and promising to follow them later.

"Once we left the door of the house, we started running and didn't look back. I was so scared, but we had to do it.

"We had to run in the dark for very long distances, not knowing exactly where we were going or what was waiting for us next. All I was able to think about then is the moment when this nightmare would be over, and my fear that something could happen to my baby.

"We kept running for more than 10km (six miles) till we found Iraqi forces near a screening centre."

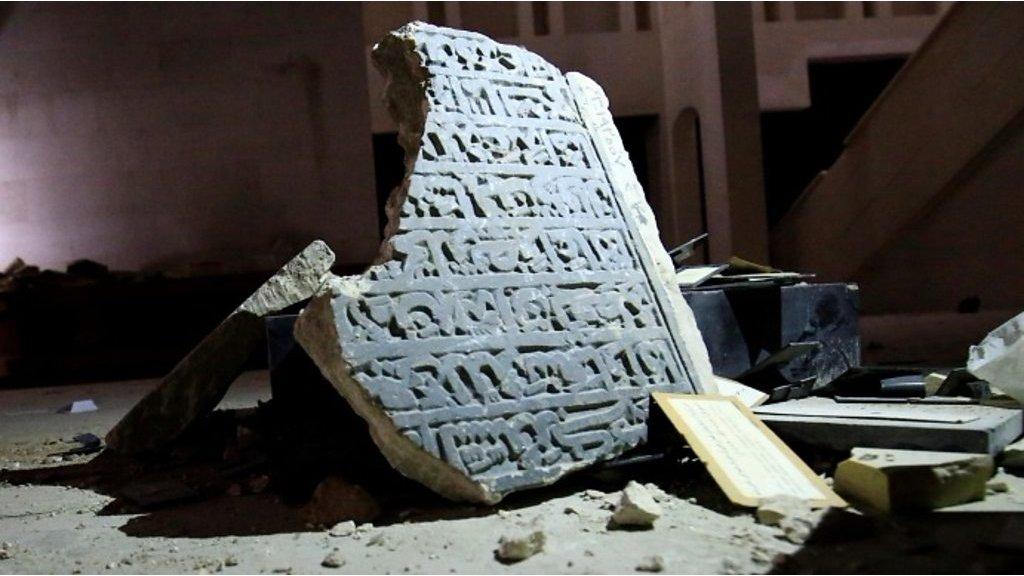

Many of the doctors at the Qayyara clinic are graduates of Mosul University, a once-proud institution that was among the best research centres in the Middle East. Recent pictures of the library reveal a burnt-out shell - another casualty of IS brutality.

Dr Badri, a gynaecologist, left the city with her son. She says being pregnant there is hell, as IS has erased women's rights and confined them to their homes without pre-natal care. Treating pregnancy complications is nigh-on impossible.

"I had no medical equipment and only limited medical supplies in stores," she sighs.

Once she saw medicine simply as work. Now, she feels a joy in using her skills to help women abused and traumatised by IS.

Orla Guerin hears from civilians who escaped IS in Mosul

"I feel so happy to be able to resume my job. It's a great feeling to be able to help in delivering new lives and bringing happiness to families … What I do here in this delivery room means so much to me," she said.

The nursing team at the UNFPA-funded clinic in Qayyara came together only recently, but Dr Badri says they've bonded in adversity.

"We work together. We share our difficult moments and also enjoy a lot of happy moments, especially when a new baby is safely delivered through our help," she says.

"Delivering happiness is our job!"

*The BBC has changed all interviewees' names to protect their anonymity.

- Published4 April 2017

- Published3 April 2017

- Published3 April 2017

- Published2 April 2017

- Published31 March 2017

- Published25 March 2017

- Published10 March 2017