The joy and sadness of returning to Mosul

- Published

Basheer and Kareem had not seen each other for 14 years

I've dreamed of going back to Mosul for so long.

The city where I was born and grew up has always occupied a special place in my heart and it's full of happy memories.

My Mosul was a city of green and shady streets, with beautiful, old houses overlooking the River Tigris.

It was a city of books with a famous university where my father taught and I studied.

It was a place where Iraqis came for a break, to breathe its cool, fresh air and visit its world-renowned archaeological sites.

I hadn't been home for more than a decade, and knew that after two brutal years of occupation by so-called Islamic State (IS), Mosul had suffered much damage.

But it was still a shock to see it for real.

Heartbreaking homecoming

As we drove through the streets where I played as a child, I found myself fighting back the tears.

Familiar places had become almost unrecognisable.

Everywhere you looked there were bullet-scarred walls and bombed-out buildings.

The roads were littered with twisted metal and burned out cars.

It was a heartbreaking homecoming.

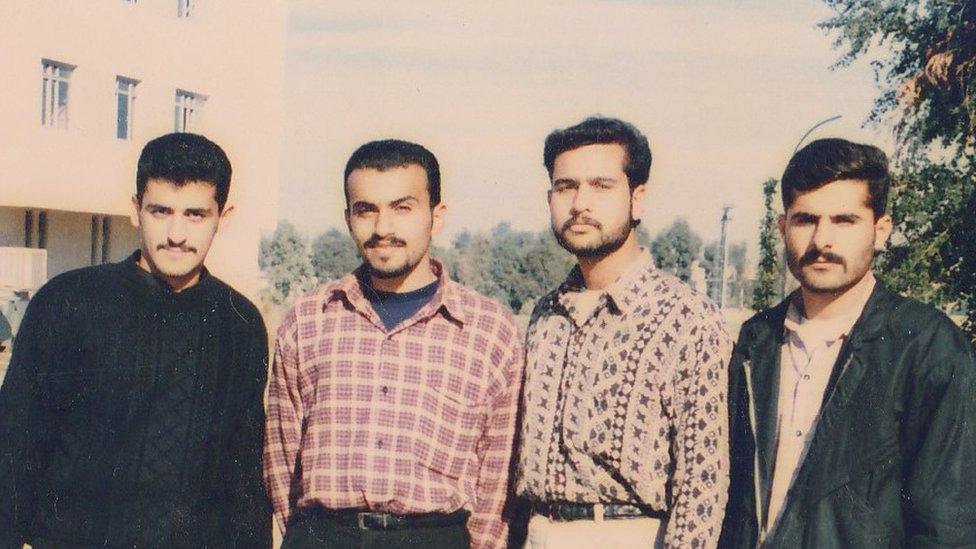

Basheer (centre left) and his best friend Kareem (centre right) studied at Mosul University in the 1990s

The main road into Mosul was full of trucks bringing in supplies, and ambulances, sirens wailing, ferrying out the sick and injured.

Eastern Mosul, where I used to live, was freed from IS control in January but a fierce battle continues over the western side of the city.

IS militants in the west are sending a daily barrage of mortars and armed drones to disrupt life in the east, and there are frequent suicide bombings.

The peace in eastern Mosul is so fragile that we had to travel with an Iraqi army escort.

My first stop was the home of my oldest friend, Kareem.

We grew up together and had always kept in touch until IS occupation made it too dangerous.

We drew up outside Kareem's house and suddenly there he was.

We hugged each other and cried - so happy to see each other, but so sad at everything that had been lost since we last met.

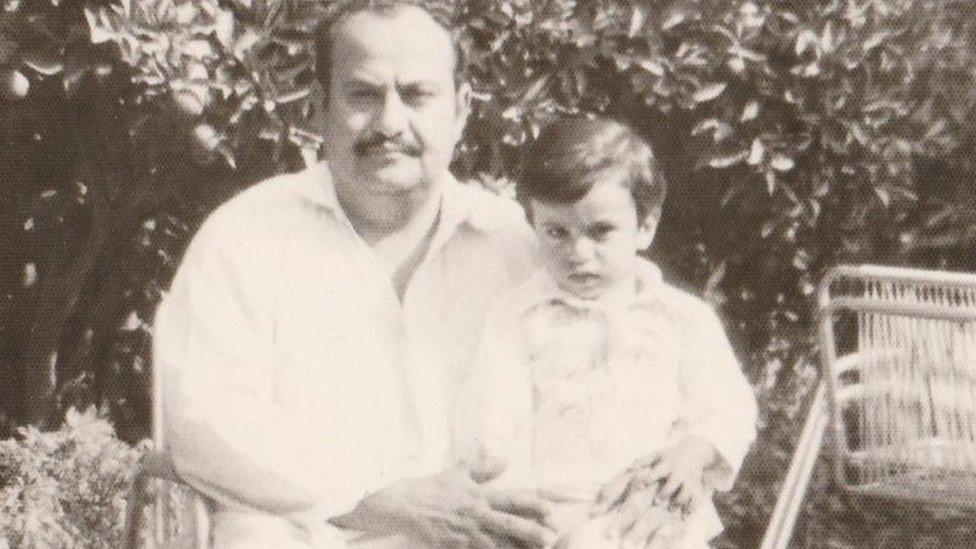

Basheer as a child with his father, Kasid, who taught Arabic Linguistics at Mosul university

Over glasses of tea, Kareem told me what it had been like to live under IS.

Like many in the city, he had at first welcomed the militants. It was shocking, but unsurprising to hear.

In the chaos and violence of the post-Saddam era, Mosul was rife with corruption and sectarian tension.

The largely Sunni local population hated the Shia-dominated central government and army who they blamed for their troubles.

"We thought IS were revolutionaries here to help people and restore social justice and fairness," Kareem said.

But his support was short-lived as the realities of everyday life in the "caliphate" became clear.

Hope was soon replaced by fear as arrests, public executions and floggings became a daily occurrence.

Eastern Mosul, where Basheer grew up, suffered heavy damage during weeks of fighting

The militants took over houses in my and Kareem's old neighbourhood. It was such an eerie feeling for me to know that.

Kareem's beloved elder brother, who worked for the Iraqi electoral commission, was detained and executed.

"His last wish was to hug and kiss his five children before he died," said Kareem. "But they didn't let him."

As a journalist, Kareem also feared arrest and he moved many times to keep out of sight.

But there were also occasional moments of humour.

We remembered another friend of ours, who kept pigeons - a popular pastime in Mosul until it was banned by IS.

The friend had apparently used the birds to fly illicit supplies of cigarettes - also banned - to another friend in a different part of the city.

We both laughed at the story, but I could see that Kareem was not the same person I used to know.

He looked shaky and I could see fear and uncertainty in his eyes.

Although he's back in his own home now, like most people he has no electricity, no water and relies on gas canisters to cook and heat water.

Many people in Mosul say they won't really feel at ease until the whole city is free.

"Imagine Mosul as a pair of lungs," one old man told me. "It's made up of two parts. You can't be healthy with only one."

Hunting IS

Everyone is afraid the militants will come back, and the security forces are on constant look out for sleeper cells.

One morning we joined the National Security Service on a raid to arrest suspected IS collaborators.

It was a surreal experience.

Basheer bumped into an old neighbour while on a police raid

The suspects' house turned out to be on the very same street where I lived when I was at school.

As we climbed out of the police vehicle, in helmets and body armour, surrounded by heavily-armed police, an old neighbour recognised me and cheerfully waved.

It was a reminder of the way violence and ordinary life co-exist in Mosul.

We watched the police storm the house, grabbing the suspects in full view of terrified wives and children.

They said they'd spent weeks building a case against the men.

I hoped they'd got the right people.

Restoring security in Mosul is a delicate business and the way the security forces behave now will determine whether they keep or lose the trust of people here.

Glimmer of hope

On my last day in Mosul we drove around the city and it was good to see life slowly returning.

Women's dress shops and beauty salons are re-opening. Men have started wearing jeans and t-shirts again.

But best of all were the schools.

Many children are going back to school for the first time since 2014

My visit coincided with the week when hundreds of Mosul children finally went back to school.

Many had been kept at home to avoid an IS education.

It was uplifting to see crowds of happy, young faces at the school gates. Excited boys and girls, with school books in backpacks, crowded around our camera.

Their laughter filled the air, and for a moment, despite all the uncertainty and chaos of life in Mosul, I saw a glimpse of hope for the future.

Return to Mosul is on the BBC News Channel on Saturday 1 April and Sunday 2 April at 2030 GMT, and on BBC World News on Saturday 1 April at 0030 GMT and 1730, and Sunday 2 April at 0530 GMT

- Published29 March 2017

- Published10 July 2017

- Published5 October 2016