How the Six Day War brought elation and despair

- Published

Rival claims to East Jerusalem remains one of the most burning issues

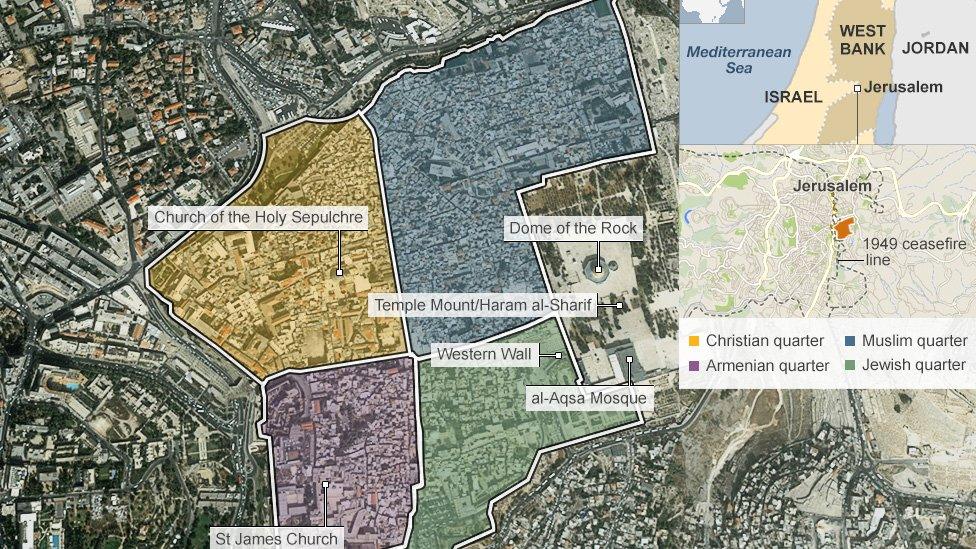

From a monastery rooftop just outside Jerusalem's ancient walls there is a spectacular view of the Dome of the Rock, rising in gold above the Old City.

The author Meir Shalev was brought to this spot as a boy to look across at the Western Wall - which at the time could not be accessed by Israelis.

He would gaze at the top few bricks of this holy Jewish site while his father told him: "You will grow up, you will become a soldier and you will fight over this city."

At the time Jerusalem was divided between Israeli and Jordanian control.

It followed the 1949 armistice that divided the new Jewish state of Israel from other parts of what had been British Mandate Palestine.

For Meir Shalev's father, a well-known Israeli poet, the exclusion of Jews from their holiest sites represented a tragedy for his people.

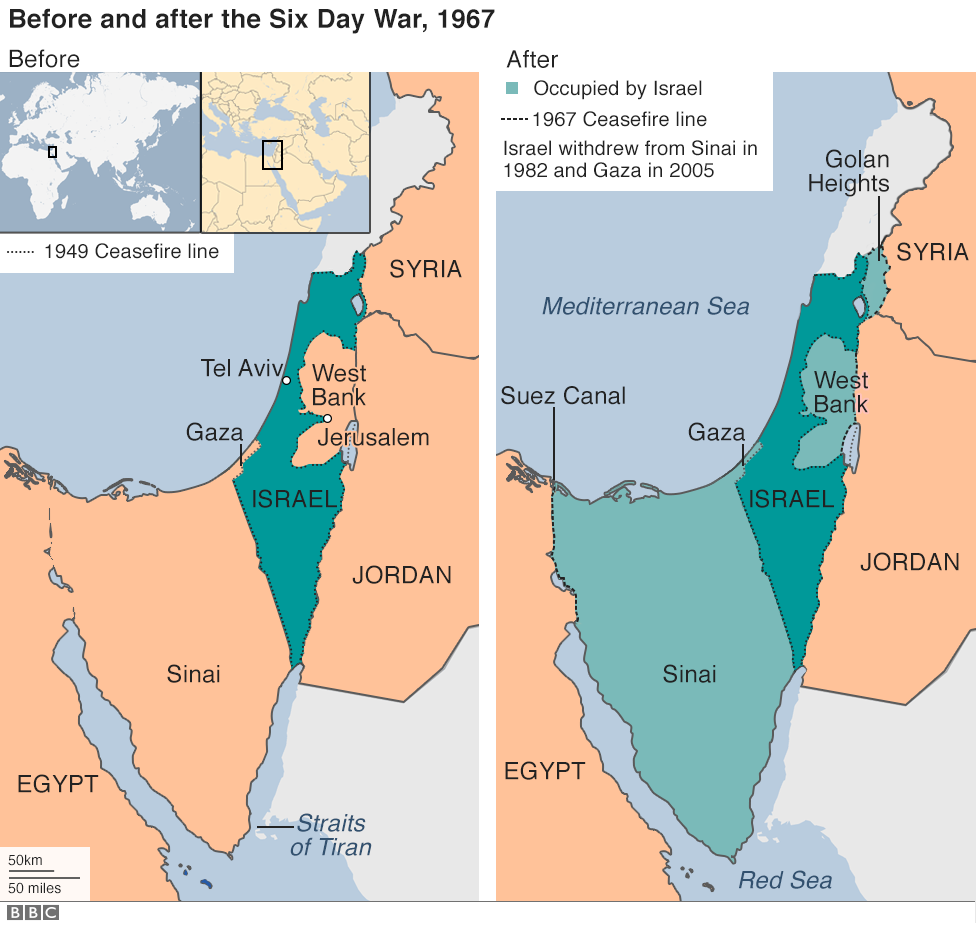

The outbreak of war on 5 June 1967 would change many lives - and reshape that part of the Middle East.

Occupation legacy

Israel launched a pre-emptive attack on Egypt and battled Jordanian and Syrian forces the same day.

Mr Shalev was about to turn 19 - the age of his country at the time - and remembers a national mood of panic before the conflict.

"People were talking about the possibility of Israel being destroyed and us being exiled or killed," he says.

"We were very eager to fight," he remembers. "We thought: 'This is our chance'."

Meir Shalev: We cannot hold on to the West Bank

Mr Shalev found himself in action against Syrian troops on the Golan heights during a series of battles that would lead to Israel's capture of that territory.

But it was the occupation of the West Bank that he believes consumed Israel's energy - something he says it has had to "deal with" ever since its victory in 1967.

He recalls how after the war he told his father in a heated confrontation: "We took a bite we will suffocate on."

Other Israelis saw a divine purpose in the fighting to bring a return to their biblical Jewish lands.

'A miracle'

In Jerusalem, the conflict saw Israeli troops involved in close quarters fighting with Jordanians.

Another young soldier, Yoel Ben Nun, was being transported to a checkpoint that separated control of the city.

Yoel Ben Nun: 'I saw a miracle'

He speaks of surrounding the Old City at night, facing a battalion of the Jordanian Legion which rapidly retreated.

"That was a miracle," he says, recalling Israel's victory in six days.

Yoel Ben Nun told his commander at the time that he felt like two millennia of history had passed.

"The meaning was that for 2,000 years the people of Israel were in exile - persecuted, tortured, subjected to anti-Semitism. Those 2,000 years were over," he says.

"This is what I felt on the Temple Mount at the time," referring to the revered hilltop also known to Muslims as Haram al-Sharif.

Yoel Ben Nun later became a rabbi and joined the movement building Jewish settlements in the West Bank - the territory that Palestinians want for a future state.

The settlements are considered illegal under international law, though Israel disputes this.

'Still suffering'

For Palestinians, the war represented the loss of land following what they saw as the catastrophe of the first Israeli-Arab conflict two decades earlier.

Fatima Khadir was eight years old in 1967 when her family - whom she says were already displaced from their village in the previous war - fled Jerusalem's Old City.

She points to the side of her left eye, explaining she was injured by shrapnel from the debris of Israeli bombing.

Fatima Khadir: 'We are still suffering'

"I was looking around me, everyone was grabbing whatever they could - mothers and fathers carrying their babies and children".

She ended up with her parents in a refugee camp in the desert border area of Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

Fifty years on, from her home in East Jerusalem, she speaks of her desire to return to her family's village of the 1940s.

"I still feel the hurt, pain and intolerable struggle," she says.

"We were never able to go back. I'm still hurting. We are still suffering."

Shock defeat

The outbreak of war had been accompanied by enthusiastic, but false, radio reports of Arab success in the fighting.

Azzam Abu Saud: 'We were completely defeated'

Mahmoud Erdisat was training to be a fighter pilot - and would later become a major general in the Jordanian air force.

"We were very excited that finally we would get the chance to fight the Israelis and get Palestine back," he recalls.

But he says it soon became apparent that Israel was overwhelming its opponents.

The Israeli territorial increase, claims Mr Erdisat, made it harder to negotiate a "just solution" on the issue of Palestinian statehood.

He believes the Arab defeat also had a profound impact on the way Israel's neighbours came to view themselves.

"It was a blow to Arab nationalism," he says.

But its legacy further fuelled Palestinian national aspirations.

Occupation became central to their calls to activism and militancy, placing it firmly on the international agenda for years to come.

- Published30 October 2014

- Published14 January 2017