Will Syria's war criminals be let off the hook?

- Published

For six years, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Syria, external has been painstakingly gathering information about possible war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the conflict.

The investigators have produced 13 reports, the evidence in each is harrowing. Villages destroyed, crops burnt, wells poisoned, torture, rape, starvation sieges, mass bombing of civilians, and what only a decade ago might have been unthinkable - chemical weapons.

There is no doubt that war crimes have been committed by all sides, the commission says. In each report there is a demand for "accountability" - that no-one should be allowed to commit such horrific acts and get away with it.

"This would be incredible, a scandal," says commission member Carla Del Ponte, who describes the violations in Syria as by far the worst she has ever come across. "But nothing happens, only words, words, and more words."

Ms Del Ponte, as a former prosecutor at the tribunal for Yugoslavia, and the woman who put Slobodan Milosevic in the dock, knows how to bring war criminals to book.

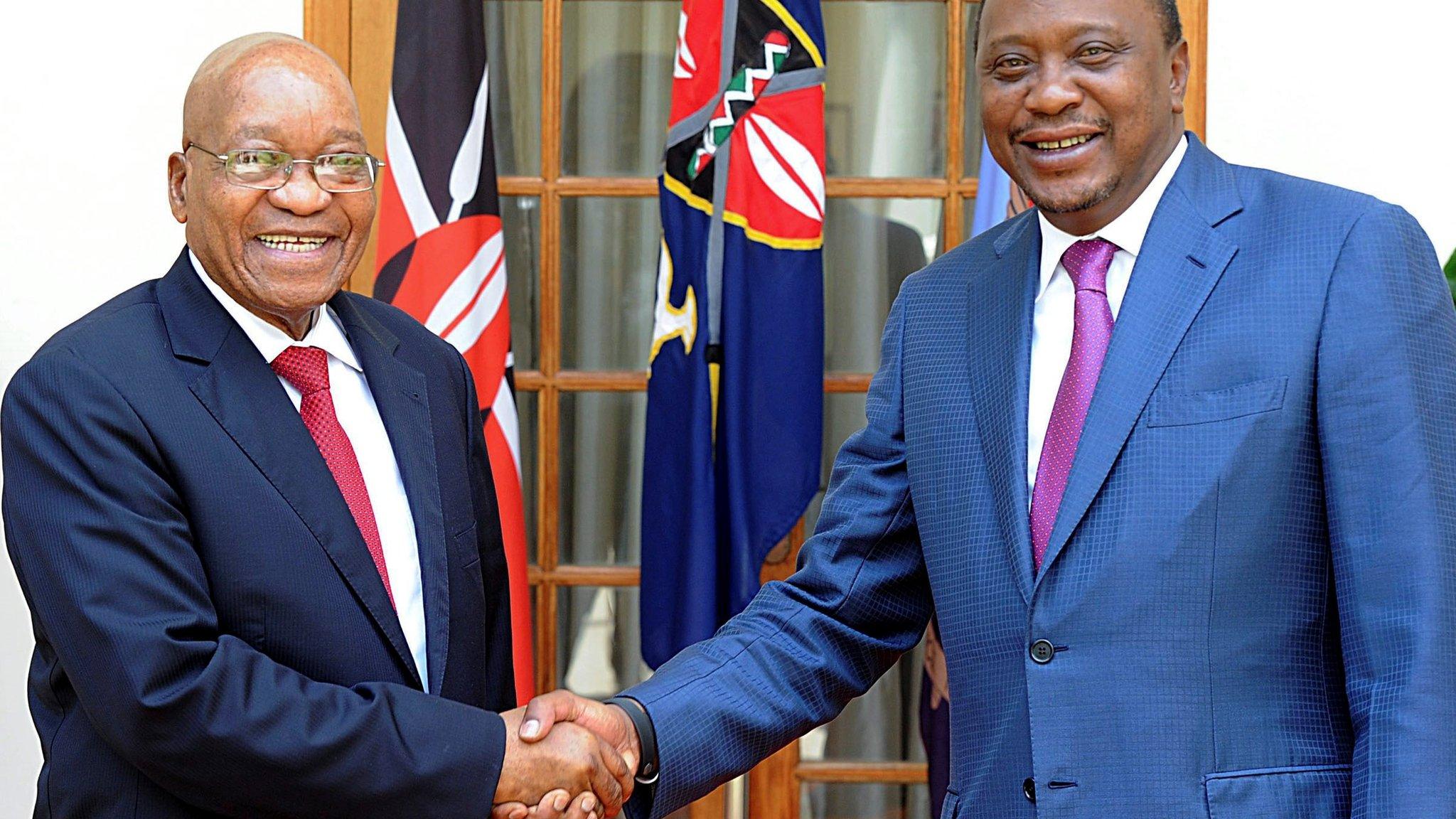

Carla Del Ponte says the violations of international law in the Syrian conflict are the worst she has encountered

While the Syria commission has no power to prosecute, what it does have is a vast amount of evidence, and a confidential list of names, thought to include figures at the very top of the Syrian government and military.

To bring those individuals (including, Ms Del Ponte thinks, President Assad) to court, the UN Security Council would have to refer Syria to the International Criminal Court. And throughout the Syria conflict, the Security Council has been divided, with Russia and China in particular resisting what they regard as unnecessary interference in Syria's problems.

Now, though, the United Nations, under new Secretary General Antonio Guterres, appears to be flexing its muscles.

A new body has been set up, called, rather dryly, the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism or IIIM, to sift the evidence, build cases, and pass them to any court that could have jurisdiction. Some European countries are already opening cases.

At its head is an experienced French judge, Catherine Marchi-Uhel, who has worked on the tribunal for former Yugoslavia, and the Extraordinary Courts of Cambodia, which prosecuted the Khmer Rouge.

"This gives me hope that something is moving," says Alain Werner, director of Civitas Maxima, external, a Swiss organisation that works to ensure justice for victims of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

"I didn't even think this body would be set up… this is proof [the UN] is serious."

Mr Werner's own organisation has already built cases against suspected war criminals from Sierra Leone and Liberia, and his work with victims has shown him, he says, that "the eagerness for justice is immense".

One of his colleagues, Antonya Tioulong, knows personally just how important this can be. Her sister and brother-in-law were tortured and murdered in Phnom Penh's notorious S-21 detention centre during the reign of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

In 1995, Srebrenica was the scene of the worst massacre of the Bosnian war

In the 1990s, almost two decades after her sister's death, Antonya was able to learn what had happened to her, and she tried to bring a case in the French courts against the Khmer Rouge officers who had run S-21. It was rejected.

"I felt powerless. There was no sign, either, of an international tribunal. I wondered, 'Were the two million victims of the Khmer Rouge genocide so unimportant in the eyes of the world that the criminals did not need to be judged?'"

Antonya had to wait until 2008, when an international tribunal was finally set up. The men who murdered her sister were at last convicted.

She was comforted not just by the verdict, but by the fact that the tribunal was public.

"Thousands of people came from all over the world to attend the hearings in person, showing their desire to understand what happened."

But many thousands of victims still wait. In the Swiss capital, Berne, the Red Cross Centre for Victims of Torture and War, external had more than 4,000 consultations in 2016 alone.

"Almost the most important thing is that they have the space and time to talk," says psychologist Carola Smolenski. "We have patients from former Yugoslavia who still suffer chronically from their experiences."

For many of these patients, however, there may never be a public tribunal where perpetrators are convicted, and the suffering of their victims formally recognised in a court of law.

Instead, the Red Cross Centre has included a form of "validation" process as part of the therapy.

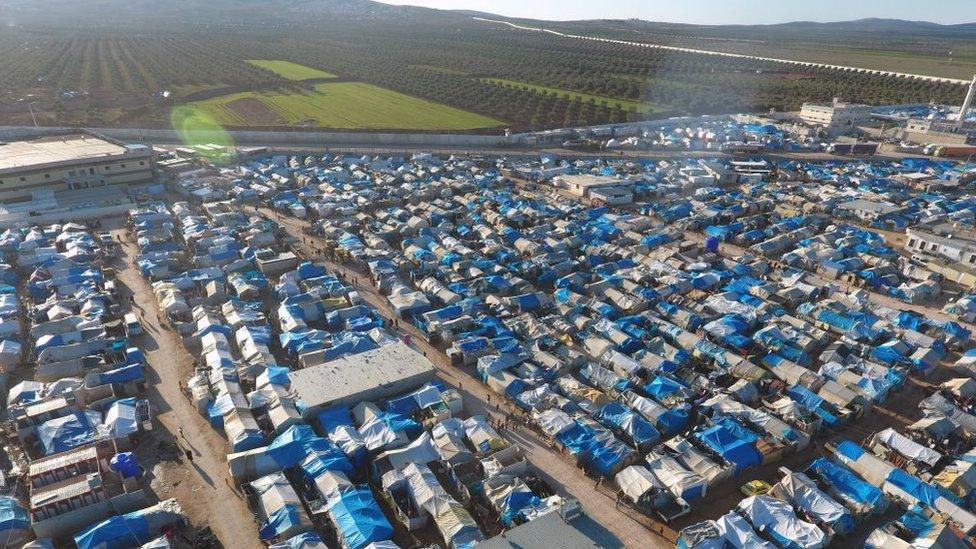

Many Syrians, millions of whom are in refugee camps, still await news of loved ones

"We will prepare [together with the patient] a detailed chronological report," says Carola Smolenski. "We recognise the experience together, and we sign it as witnesses."

"It is important that they can say, 'That is my story, and it is being taken seriously.'"

For the millions of Syrians waiting in refugee camps, or trapped in besieged cities, peace cannot come soon enough. But millions of Syrians, too, are waiting to know the fate of loved ones who disappeared into Syria's prisons, or vanished in the heat of battle.

In Geneva, the UN peace process is inching along. In the talks about Syria in the Kazakh capital, Astana, the Russians, Turks, and Iranians are working to negotiate "de-escalation zones" to reduce the violence.

But in neither the Geneva process nor Astana is there much talk of accountability for the undoubtedly massive number of war crimes and crimes against humanity. It is unclear whether the newly formed IIIM has a role in the peace process at all.

Could this be because leaders, on all sides of Syria's conflict, might not be motivated to reach a peace deal if they thought a war crimes trial would be their reward?

"You might have put your finger on it," says one Western diplomat, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The idea that achieving peace, or at least an absence of war, should take priority over justice is often advanced during tricky diplomatic negotiations.

Some also suggest that war crimes tribunals can sow the seeds of future discord, particularly if victims are from one ethnic group and perpetrators from another.

The Nuremburg war trials resulted in many convictions but little remorse, says UN human rights commissioner Zeid Ra'ad al Hussein

Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town the Most Reverend Desmond Tutu famously did not want a tribunal for South Africa, pushing instead for a truth and reconciliation process, in which the accused would acknowledge their crimes but also be forgiven by their victims.

The UN's human rights commissioner, Zeid Ra'ad al Hussein, agrees that creating sustainable peace is a complex process, but insists that the authors of Syria's suffering must be formally prosecuted.

"In Syria, there will never be peace if you don't put the victims at the centre of your effort," he says.

"You can have the most finely crafted agreement, but if victims don't feel justice, then it is worthless, a pointless exercise. There has to be an accounting, the central authors must be brought to book."

Nevertheless, he sees prosecutions as only part of the process.

"At a fundamental level, we will never have permanent peace if we don't deal with unresolved issues."

This means, he says, all sides in a conflict recognising their conduct, and showing "contrition".

And there, Mr Hussein says, society must play its role.

During the German trials after World War Two, he points out, there were 7,000 convictions, but few of those convicted showed any remorse.

The push for contrition and remorse came later, through work by German historians, school teachers, and post-War politicians.

Alain Werner agrees that, in view of the scale of the atrocities in Syria, "it is very difficult to think there will be no justice".

But, he adds, because the number of cases is "staggering", justice is unlikely to be swift. "Syria could take 40 years… even 100 years to investigate."

- Published21 October 2016