Iraq's minorities fear for their future

- Published

Sheikh Mirza, many of whose Yazidi community have been killed or enslaved

A slight octogenarian dressed in loose white garments, Sheikh Mirza looks an unlikely warrior against the fighters of so-called Islamic State (IS).

Nevertheless, the Yazidi leader says that when they approached his ancestral village two years ago he left Lalish - the holy site where he usually resides - for the frontline.

"I picked up my weapons and stood there. I preferred to be killed rather than see them advance," he explains.

"These terrorists, these sons of donkeys, they hurt our people so much. God will take back our rights."

Besides its Shia and Sunni Muslim communities and mixture of Arabs and Kurds, Iraq has a wide range of other religions and ethnicities.

Minorities had been hit by waves of violence and turmoil since the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq. Then, IS singled them out for attack.

Among the worst affected have been the Yazidis, Christians, Turkmen, Shabak and Kakai.

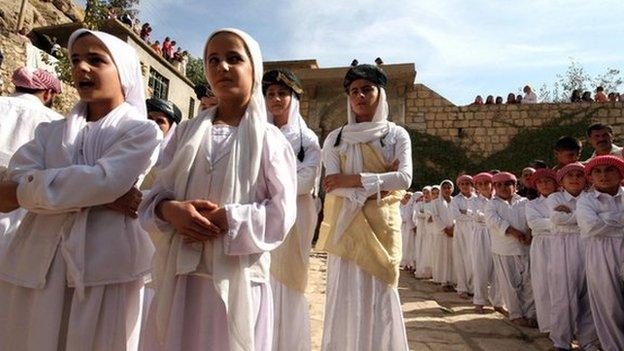

The Yazidi are followers of an ancient faith who revere a Peacock Angel. IS denounced them as devil worshippers.

IS devastation

In August 2014, the jihadists moved into the area around Mount Sinjar - home to about 400,000 Yazidis. UN human rights experts refer to what happened next as genocide, external.

Thousands were killed and more than 6,000 sold into slavery or forced to become child soldiers. It is believed more than 3,000 are still being held captive.

"All my family is split up. My father is missing. My brothers were kidnapped," says Shireen, who escaped from slavery in Mosul. "We still have one sister held by IS."

Huri (L) and Shireen feel unable to go back home

Shireen and her grandmother, Huri, live in Khanke camp, near Dohuk. Like many displaced Yazidis, they cannot yet envisage returning home.

"Some of us stay because we don't have houses. They were destroyed by IS or US air strikes [against IS]," Huri explains. "Without our men, we can't rebuild."

Yazidi survivor: 'I was raped every day for six months'

Another problem is that Sinjar, like other parts of northern Iraq, is now under control of the Popular Mobilisation, a paramilitary force largely made up of Iranian-backed, Shia Arab militias formed to fight IS.

Non-Shia civilians fear some of these militias.

Who are the Yazidis?

Yazidis revere the Bible and Koran - but much of their tradition is oral

Centuries-old religion found in northern Iraq, Syria and the Caucasus

It incorporates elements of many faiths

Principal divine figure, Malak Taus (Peacock Angel), is the supreme angel of the seven angels who ruled the universe after it was created by God

Many Muslims and other groups incorrectly view Yazidis as devil worshippers

There are estimated to be about 500,000 Yazidis worldwide, most living in Iraq's Nineveh plains

All minorities have safety concerns.

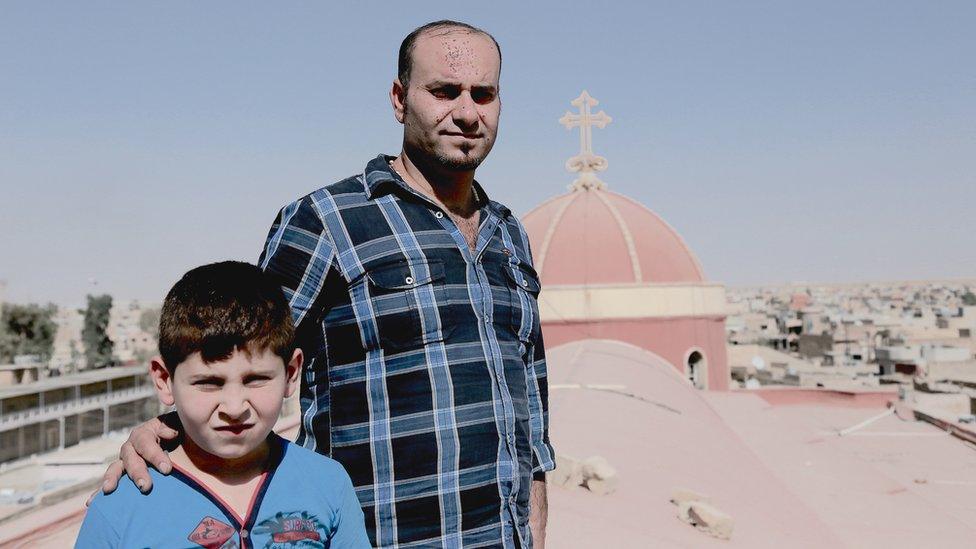

Qaraqosh, near Mosul, was once the country's largest Christian town. It was liberated from IS by Iraqi forces last October, but few residents have moved back.

"In Iraq there's no justice or security," says Marwan Yashua as he shows me around a Syriac Catholic church that the militants set ablaze.

Some of Iraq's minorities complain of marginalisation by the Shia Arab-led government

"You don't know when another group will come with the same extremist thinking as IS or worse."

"Baghdad isn't offering us protection," Marwan adds. "Our areas are devastated and the government doesn't look at us. There's no compensation. Nothing."

In 2003, there were about 1.4 million Christians in Iraq.

Affected by soaring sectarian violence, more than two-thirds had left by the time IS arrived just over a decade later. Tens of thousands more subsequently left - many moving overseas. It is estimated that between 250,000 and 350,000 remain.

Iraq's dwindling Christian population is one of the oldest in the Middle East

"Even now with [IS] gone from many population centres, the future of the minority communities continues to look very bleak," says Mark Lattimer, director of Minority Rights Group International.

"Iraqi communities are still in desperate fear that other forces - including the Shia militias and the big players of the country - will edge them out, using the opportunity to effect a land grab of their traditional properties."

Sectarian rifts

The political and ethnic allegiances of minorities, many of whom live in areas claimed by both Arabs and Kurds, are being tested by ongoing developments.

These include a Kurdish referendum on independence due to be held on Monday.

Hundreds of thousands of Iraqi Christians have fled the country since 2003

IS - Sunni Muslim extremists - have also stirred up internal divisions within religious and ethnic groups.

Three years ago, amid fears of persecution, some leaders of the secretive Kakai faith declared their people were actually Muslims. Others in the community, which has 110,000 to 200,000 members, were outraged.

Meanwhile, Turkmen - of whom there are between 500,000 to 3 million - have been split along sectarian lines.

When IS arrived in areas such as Tal Afar, Sunni Turkmen were allowed to stay while Shia Turkmen were expelled.

It was the same with the Shabak, who number between 200,000 and 500,000. Most are Shia, but some Sunni Shabak remained when IS took over their lands around Mosul and on the Nineveh plain.

Seeking justice

As Iraq moves towards a post IS era, minority groups are leading calls for justice.

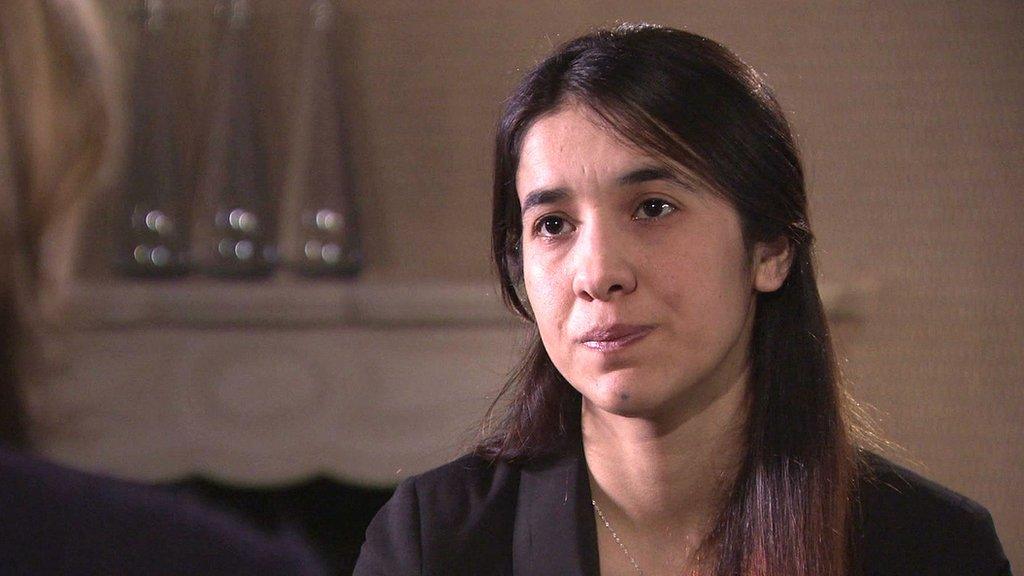

International human rights lawyer Amal Clooney and Nadia Murad, a Yazidi woman who was enslaved and raped by IS fighters, pushed for a UN inquiry.

Amal Clooney and IS victim demand justice for Yazidis

Last month, the Iraqi government officially asked for international help, external to collect and preserve evidence of the militants' crimes.

The UK Foreign Office worked with Baghdad to draft a UN Security Council resolution to establish the investigation, which was approved unanimously on Thursday.

"It's very important," says Murad Ismael, director of Yazda, a Yazidi advocacy group.

"Without justice how can we go home, rebuild our lives and co-exist with Iraq's other communities?"

- Published29 August 2017

- Published29 February 2016

- Published8 August 2014

_cut.jpg)

- Published7 March 2017

- Published21 July 2014

- Published4 November 2016

- Published3 August 2016