The archaeological treasures IS failed to destroy

- Published

A soldier walks past a smashed artefact at Nimrud

The rich archaeological heritage of Iraq suffered grievous damage at the hands of so-called Islamic State. As its fighters are driven back, British Museum teams are among the first to assess the extent of the destruction.

After IS declared a caliphate in the summer of 2014, thousands of archaeological sites in Iraq fell into the hands of its fighters.

Terrible acts of vandalism followed, with videos released by the group showing its members smashing artefacts at Mosul Museum and blowing up parts of the site of the Assyrian capital of Nimrud.

Archaeologists returning to areas recaptured from IS have found other ancient sites turned into car parks, statues smashed and manuscripts disappeared.

But there is good news too - with IS having failed to destroy many artefacts, previously undiscovered treasures found amid the ruins, and the first modern explorations of sites it never captured revealing exciting new finds.

Bulldozers and sledgehammers

Only recently liberated from IS fighters following a huge military operation, Iraq's second largest city of Mosul - and the area that surrounds it - is of great historical importance.

The Assyrian city of Nineveh, which dates to the 7th Century BC and once hosted palaces, temples and mansions, is on the outskirts of modern Mosul.

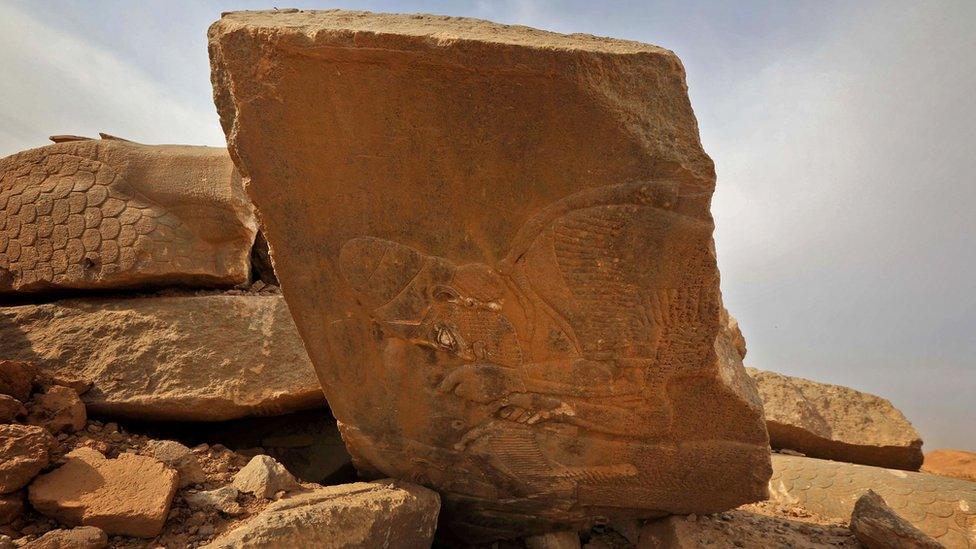

The lamassu on the right of the Nergal Gate, photographed in 1977

It has been 70% destroyed by IS, with parts of the walls bulldozed and gates which had been excavated and restored knocked down.

Magnificent winged bulls which guarded the entrance to the Nergal Gate have been mutilated and Nebi Yunus, the site of a palace, has suffered far greater damage than expected and is in danger of collapse because of tunnelling.

But among all this dreadful news is a glimmer of something positive.

At Nebi Yunus, it seems that IS was driven out just in time.

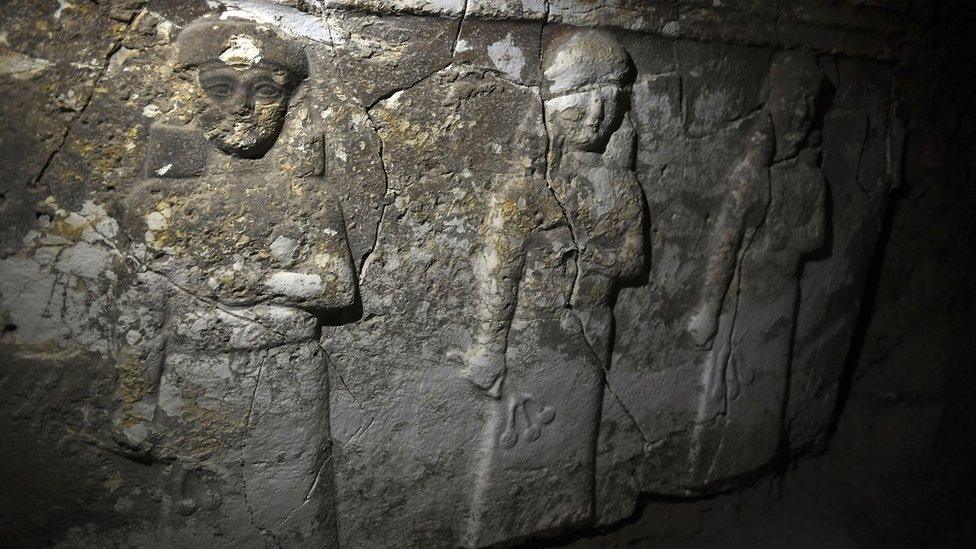

Iraqi forces found a network of tunnels, largely following the course of ancient sculptures which lined the palace walls.

Tunnels dug by IS in an attempt to find antiquities, or serve as communications routes, revealed unseen artefacts

While these tunnels have hugely damaged the archaeology of the mound, IS did not have time to loot or destroy these sculptures.

The discoveries in the tunnels - reliefs, sculptures, and cuneiform slabs - are spectacular.

The reliefs are truly exceptional, depicting religious and cultic scenes, priests, and what appears to be a demigoddess or a high-priestess.

About 20 miles south of Mosul is Nimrud, the Assyrian city of Kalhu - a great city between 1350 and 610 BC.

Excavations at Nimrud began in the mid-19th Century and continued until 1992, revealing some of the most important monuments of Assyrian art.

Since March 2015 the site has been systematically destroyed by IS - with about 80% of it lost.

IS levelled the Ziggurat - a stepped pyramid which was once more than 34m high, external - with heavy machines, its features now lost or hidden in rubble.

It also destroyed the lamassus - winged bull sculptures - in the nearby Ishtar temple and destroyed the entrance of the Nabu Temple, along with the fish-cloaked statues which flanked it.

Bulldozers and explosives were used to destroy the North-West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II, king of Assyria from 883 to 859 BC.

IS posted a video in April 2015 showing parts of Nimrud being blown up

Iraqi archaeologist Faleh Noman, who undertook British Museum training and has been appointed by the Iraqi government to lead assessment of the sites, found "barbaric" destruction.

"The main entrance to the palace leading to the throne room has been completely destroyed and the lamassu demolished.

"The wall reliefs and lamassu of the second gateway have also been damaged, with only one large wall relief remaining intact."

Inside the palace, he found that sledgehammers have been used to damage reliefs.

Iraqi forces recaptured Nimrud from IS in November 2016

Making new finds

Across the Mosul region alone, Iraqi officials believe that at least 66 sites were destroyed.

There has also been looting, with many of the tunnels dug by the extremists carved out with the aim of finding antiquities to sell on the black market: heritage turned into weaponry.

Archaeologists at Tello work under the protection of Iraqi antiquities police

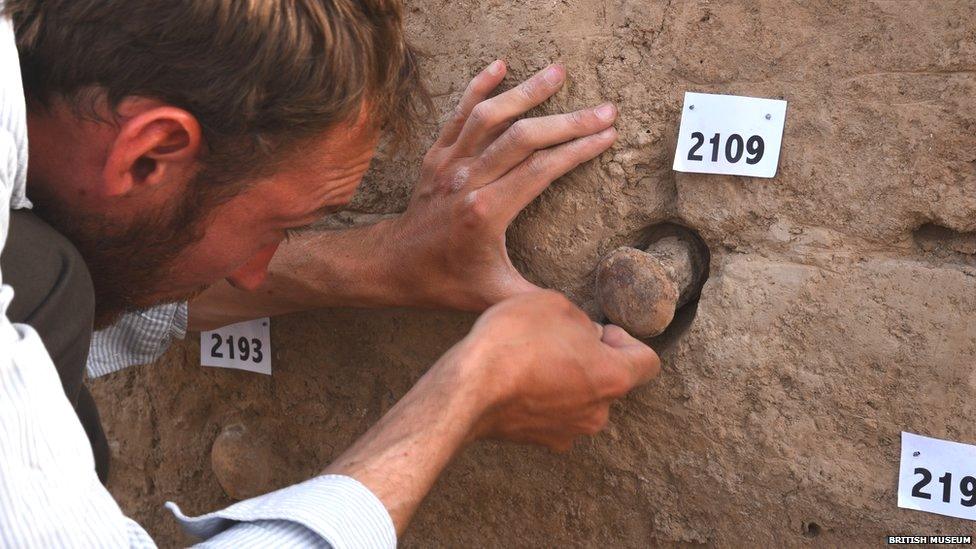

It is a situation which led the Iraqi government to appeal for international help and, in turn, the creation of a British Museum scheme to train Iraqi archaeologists in heritage management and fieldwork skills, including excavation and photography.

The training includes two field projects in areas that were never held by IS - in the south of Iraq at the site of Tello, and in a Kurdish area of the north, at Darband-i Rania.

Tello, the modern Arabic name for the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu, is one of the world's earliest known cities and is a mega-site with a layout similar to Nineveh or Nimrud.

Meet the archaeologists training to save Iraq's heritage

Following the discovery of cuneiform tablets, it revealed to the world the existence of the Sumerians, who invented writing 5,000 years ago and may have developed a form of early democracy well before the ancient Greeks.

It also includes fragile remains of monumental architecture such as the Bridge of Girsu - the oldest bridge yet found - which will be the focus of conservation works.

Excavations in late 2016 and early 2017 were carried out in the heart of the sacred district, known as the Mound of the Palace.

Mudbrick walls of a newly discovered temple at Tello are being excavated

More than 80 years after French pioneers first discovered the ruins of a Hellenistic palace, we were able to miraculously unearth extensive mudbrick walls belonging to the Ningirsu temple.

Dedicated to the storm god, this was one of the most important sacred places of Mesopotamia and widely praised for its magnificence.

However, until now it was known only by cuneiform texts and its discovery represents a significant milestone in the history of archaeological research in Iraq.

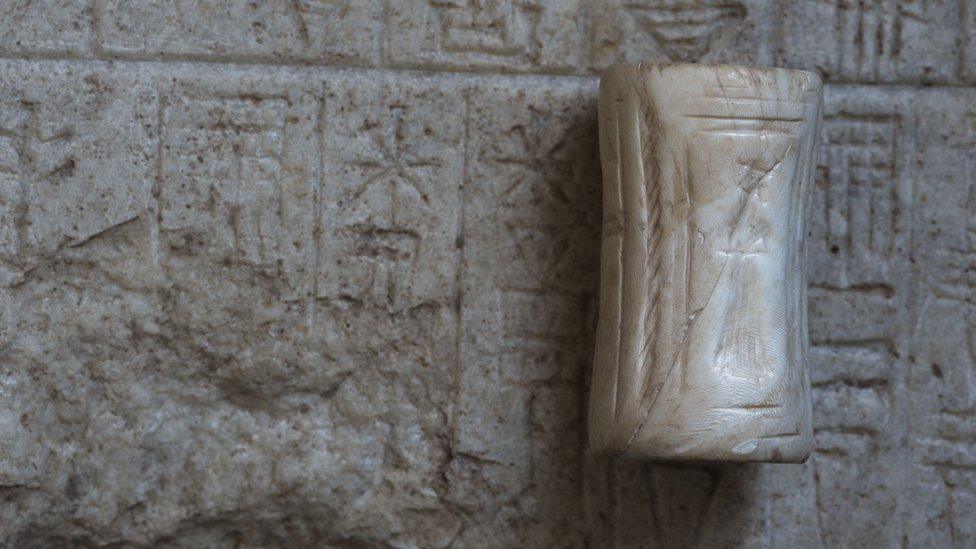

Finds at Tello include a stone foundation tablet

Of this 4,000-year-old religious complex, we have exposed what appears to be the central part of the sanctuary: a decorated entrance, the cella - with an offering altar, passageways marked by colossal inscribed stones, and also scattered remains of pavements and fired bricks.

Collapsed layers of the superstructure have yielded 100 cones, most of which commemorate the reconstruction of the temple by Sumerian rulers.

Among the unique finds were a fragment of a marble foundation tablet of the Sumerian ruler Ur-Bau, a terracotta plaque with a Sumerian couple, two cylinder seals - one belonging to a deity and the other featuring a presentation scene of deities in front of the sun god - and a unique impression of a Sumerian demon.

These objects and other important artefacts have already been safely delivered to the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.

Excavations in northern Iraq have focused on a site at Darband-i Rania

There have also been important finds at the site in northern Iraq.

Darband-i Rania is a pass at the western edge of the Zagros Mountains, on a historic route from Mesopotamia to Iran.

Alexander the Great passed through it in 331 BC, and in the 8th and 7th centuries BC it was at the eastern edge of the Assyrian empire.

We are hoping to learn more about the early imperial control of this strategic location in the first millennium BC.

The focus has been at the western end of the pass - at Qalatga Darband, external, a site overlooking the Lower Zab River which was discovered in declassified spy satellite imagery from the 1960s.

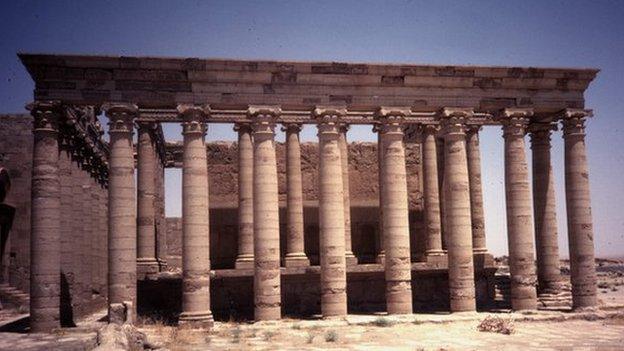

Alexander the Great passed through the area in 331 BC, with Qalatga Darband established by his successors

Large numbers of carved limestone blocks that lie scattered across the site indicate the presence of substantial remains, while drone imagery suggests the existence of large buried buildings.

Analysis of surface ceramics suggest that the site can be dated to the 1st and 2nd Centuries BC.

It appears that Qalatga Darband was founded in the Hellenistic period by the Seleucids, the successors to Alexander the Great.

The site then came under Parthian rule.

A substantial fortification wall protecting the southern and western side of the settlement appears to date to this period and makes excellent sense as the Parthians were protecting their empire from the Romans.

The presence of a large fortified structure at the north end of the site has been confirmed and stone presses hint at facilities for wine production.

Excavations have unearthed large buried buildings, ceramics and wine presses at Qalatga Darband

Investigation of a huge stone mound at the southern end of the site is uncovering remains of a monumental building which appears to be a temple for the worship of Greco-Roman deities.

And excavations at the nearby site of Usu Aska have confirmed the existence of a fort tentatively dated to the Assyrian period.

With walls six metres thick and still standing five metres high, it must have been a formidable installation for controlling movement through the pass.

The Parthians annihilated the Roman legions and captured their standards - the construction of the wall may well have been a direct reaction to the rising threat from Rome.

The ongoing work is adding a new chapter to the history of Iraqi Kurdistan, a region which, in archaeological terms, has previously been almost completely unexplored.

Cradle of civilisation

The recovery and rediscovery of these ancient sites will hopefully feed into a better future for Iraq - a country with an incredibly rich heritage.

It is the cradle of civilisation, with a huge number of remains from deep prehistory to the present day.

As parts of Iraq become safer, archaeological expeditions are once again exploring this unique heritage.

This research will generate new insights into the rise and fall of the many civilisations that have flourished here - and bring hope for the future.

About this piece.

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Dr Sebastien Rey and Dr John MacGinnis are lead archaeologists on the British Museum's Iraq Emergency Heritage Management Project, external.

The Iraq scheme is a programme funded by the UK government, through the Department of Culture, Media and Sport, and delivered through the British Museum.

Edited by Duncan Walker

- Published1 September 2015

- Published8 March 2015