The Balfour Declaration: My ancestor's hand in history

- Published

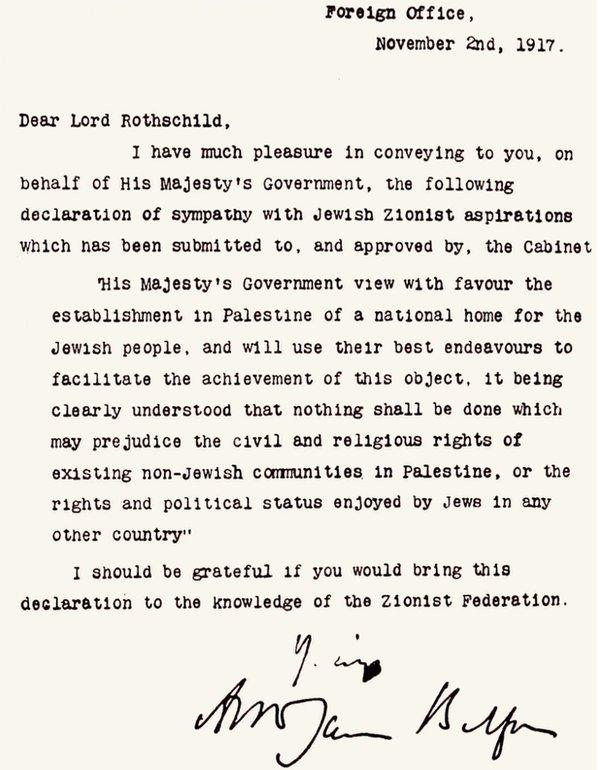

One hundred years ago, only 67 words on a single sheet of paper lit a fire in the Holy Land, igniting the most intractable conflict of modern times.

The Balfour Declaration, external was the first time the British government endorsed the establishment of "a national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine. While many Israelis believe it was the foundation stone of modern Israel and the salvation of the Jews, many Palestinians regard it as a betrayal.

I've always been drawn to the conflict which has continued ever since then, reporting on it from there for nearly 30 years.

This time, however, I went on a personal journey, to discover the role played by an ancestor of mine: Leopold, or Leo, Amery.

My mother, Olive Amery, told me stories when I was a child about this relative - a British politician involved in the drafting of the declaration. He added a sentence intended to safeguard the civil and religious rights of the majority population, the Palestinian Arabs.

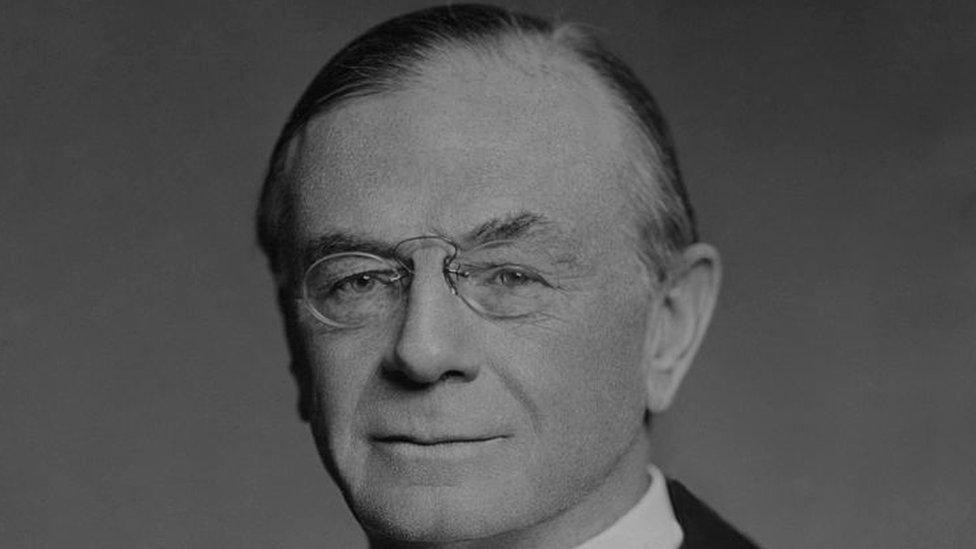

Leo Amery was one of the people who drafted the Balfour Declaration

In Lustleigh, the Devon village where my grandparents lived, I visited the church where Leo is buried and saw the plaque to his memory, bearing the words of his friend Winston Churchill paying tribute to a great British statesman.

Leo had a fascinating background: his mother was Jewish but converted and brought up her son as a Christian. He studied Islamic culture and went on to become an MP and then colonial secretary, overseeing Britain's rule during the mandate years in Palestine.

Was Leo's vision that Jews and Arabs could live and prosper together in peace doomed to failure and was violence inevitable? These were the questions I wanted to answer when I came to Israel again this time.

A total of 100,000 Jewish immigrants arrived in the first few years after the 1917 Balfour Declaration threw Britain's weight behind Zionism, the nationalist movement calling for the re-establishment of a Jewish homeland in the historic land of Israel.

During the late 1930s this provoked a backlash from the Arab population who felt threatened and the British reacted to the Arab Revolt by clamping down on Jewish immigration, just as Hitler's planned annihilation of European Jewry was about to come into devastating effect.

The bombing of Jerusalem's King David Hotel in 1946 left 91 people dead

And after World War Two, in retaliation, the Jewish underground movement attacked the British - in one of the most notorious cases, bombing the King David hotel in Jerusalem and killing British troops.

In Israel I followed in Leo's footsteps in Jerusalem, recognising when I read his diaries that the "success of violence" on both sides that so shocked him when it broke out in the 1920s was something I had seen time and again myself: four wars in Gaza, bloody protests on the West Bank and suicide bombings in Israel.

Leo was bitterly disappointed at the British cap on Jewish immigration and I visited Atlit, one of the British internment camps, with 80-year-old Rabbi Meir Lau. He spent two weeks here when he arrived in Palestine as an eight-year-old survivor of Buchenwald extermination camp. Many other refugees were turned back - to Europe.

Rabbi Meir Lau visits the former British internment camp at Atlit

"It was against humanity after six years of horror," he said, shaking his head in sorrow as we walked along the rusty barbed wire fences. "Where was the nation of the United Kingdom then? Lord Balfour would not have believed it."

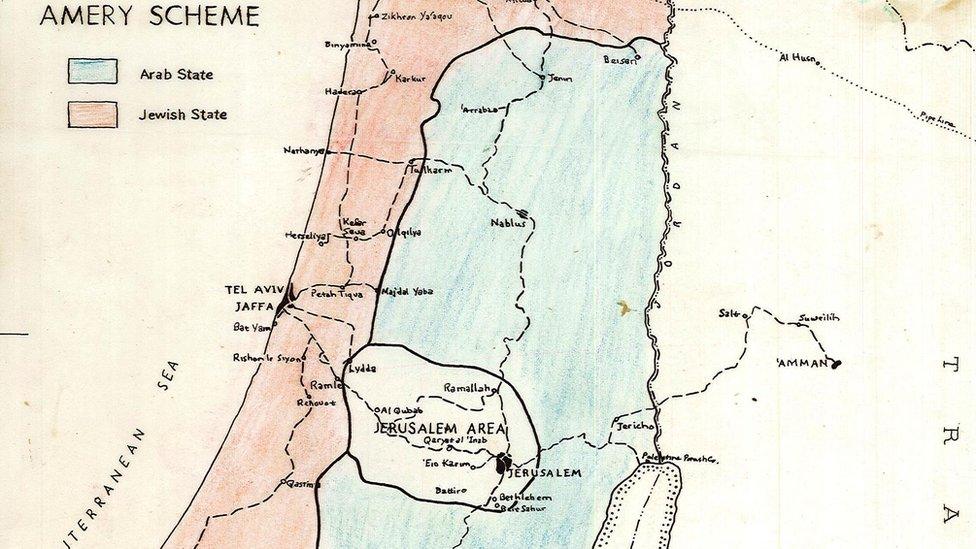

As the violence continued through the 1940s and Britain sought to rid itself of its Palestine problem, Leo had to accept the inevitability of partition. But he was working on his own solution, as I discovered in an archive in Jerusalem.

There I found his 1946 map - the Amery Scheme - to divide Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. In faded red and blue it was remarkably similar to the United Nations Partition Plan a year later which resulted in the end of British rule and the creation of the State of Israel in 1948.

But Arab countries refused to sign up to the UN's plan and, in the violence on both sides that followed, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fled or were forced to flee the new State of Israel.

The 1946 Amery Scheme sought to divide Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state

One of the most poignant moments for me was visiting the ruins of Lifta - a Palestinian village abandoned nearly 70 years ago - with some of the old residents.

Many Palestinians from here became refugees and have never been allowed to return to live in Lifta. But every year they come back with their children and grandchildren to remember.

Hamid Suhail was seven when he fled - now he leans on a stick as his son Nasir helps him down the overgrown rocky slopes.

"I hope the day will come when we will have the right to come back here and live in peace," says Nasir. Hamid's granddaughter, Sohar, is emotional as she says: "It makes me angry and sad at the same time to come here - although it is important to remember the history of these houses."

Nasir Sohail and his daughter Sohar visit Lifta, the family's former village

Leo's conviction that the energy of the Jewish migrants would soon transform the Middle East is borne out 100 years on by the skyscrapers and high-tech campuses of Tel Aviv, Israel's economic capital.

But living standards here, better than many European countries, are a far cry from the condition in which the majority of Palestinians find themselves: their economy is in crisis. And they believe it stems from what they perceive as the unfair hand that Britain dealt them with the Balfour Declaration.

The closest I have ever come to seeing Leo's vision for Palestine succeed was in the 1990s when I was the only journalist allowed behind the scenes to witness the Oslo peace process.

The Israeli and Palestinian negotiators who met secretly in Norway spoke movingly to me then of their determination to make peace.

The optimism created by the historic handshake on the White House lawn between the leaders of Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) was shattered when a Jewish extremist assassinated Israel's prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and the PLO's chairman Yasser Arafat failed to stop suicide bombings launched by the Islamist extremist group Hamas.

I went back to see the men whose story I had told nearly 24 years ago.

Yossi Beilin, the Israeli junior minister who initiated the Oslo talks, was still hopeful. "The process we began in Oslo is irreversible," he told me. "It created a legitimacy for Israel in the Arab world… and will hopefully be conducive to a permanent agreement. although much, much later than our original idea."

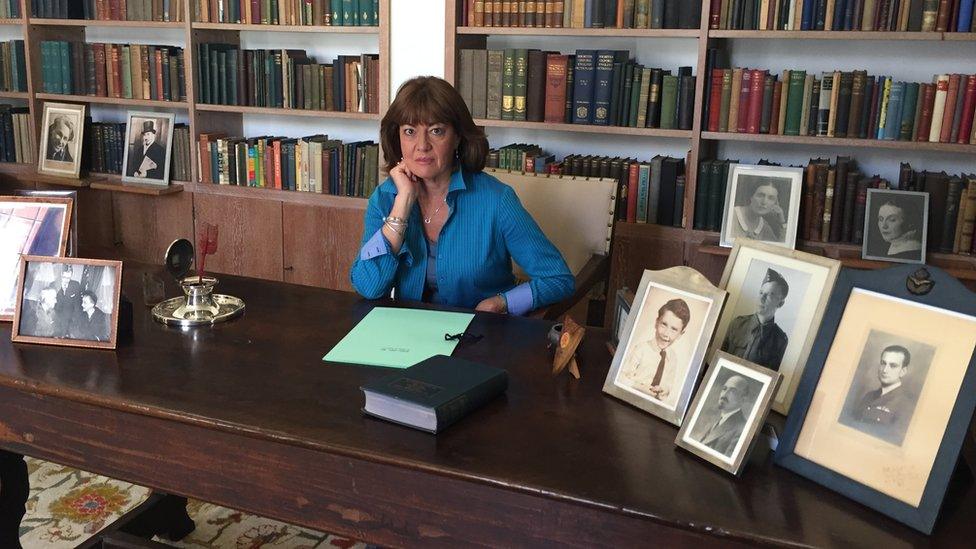

Jane Corbin at Chaim Weizmann's desk

But Ahmed Qurei, the chief Palestinian negotiator, known as Abu Ala, was pessimistic. "Unfortunately it's been nearly 25 years and a waste of time," he said. "Still the Israelis are controlling the Palestinian territory and people. It's the Israeli mentality of occupation."

My journey ended in the home of Chaim Weizmann, the first president of Israel, in Rehovot. I found Leo's name in the visitors' book - he had come here aged 76 on his last trip to Israel in 1950.

I sat at Weizmann's desk and read the correspondence between the two friends and found that Leo all those years ago recognised that Jerusalem would be the thorniest issue when it came to making peace: both sides would not compromise in their determination to have it as their capital.

And so it remains to this day as I have seen so often.

Leo never thought violence was inevitable here. He believed it was the result of wrong political decisions and the bloody and unpredictable events of history - as I discovered myself after the Oslo peace agreement.

Now there is a danger that extremism and intransigence on both sides will make peace impossible for decades still to come.

Jane Corbin's documentary, The Balfour Declaration: Britain's Promise to the Holy Land, is on BBC Two at 21:00 GMT on Tuesday 31 October and available later via BBC iPlayer.

- Published13 October 2023

- Published26 June 2023

- Published3 April 2017