Balfour Declaration: The divisive legacy of 67 words

- Published

The Balfour Declaration: 100 years of conflict

The British peer Arthur Balfour barely makes an appearance in UK schoolbooks, but many Israeli and Palestinian students could tell you about him.

His Balfour Declaration, made on 2 November 1917, is taught in their respective history classes and forms a key chapter in their two very different, national narratives.

It can be seen as a starting point for the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The declaration by the then foreign secretary was included in a letter to Lord Walter Rothschild, a leading proponent of Zionism, a movement advocating self-determination for the Jewish people in their historical homeland - from the Mediterranean to the eastern flank of the River Jordan, an area which came to be known as Palestine.

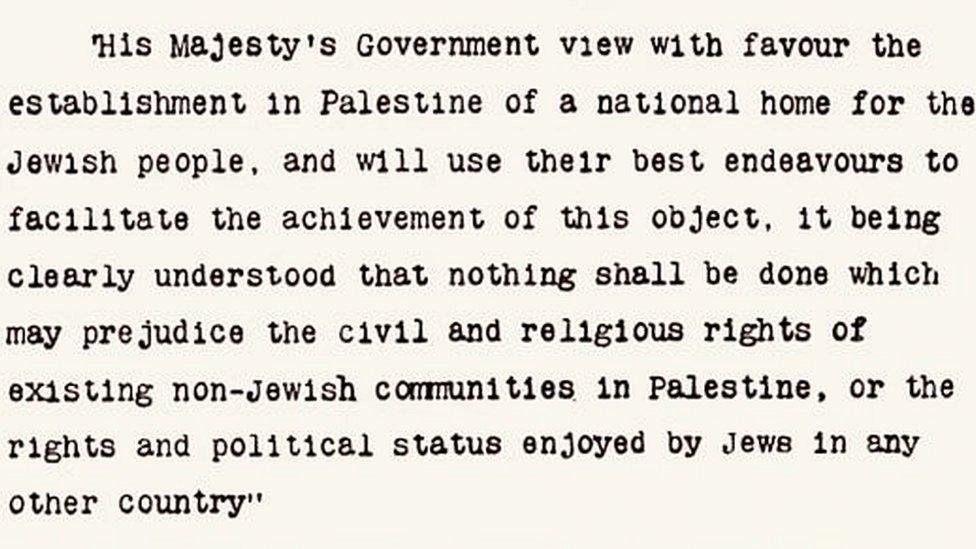

It stated that the British government supported, external "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people".

The key 67 words of Balfour's letter

At the same time, it said that nothing should "prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities".

Palestinians see this as a great betrayal, particularly given a separate promise made to enlist the political and military support of the Arabs - then ruled by the Ottoman Turks - in World War One.

This suggested Britain would back their struggle for independence in most of the lands of the Ottoman Empire, which consisted of much of the Middle East. The Arabs understood this to include Palestine, though it had not been specifically mentioned.

"Do you think Britain committed a crime against the Palestinian people?" asks a teacher during a lesson in a Palestinian school in the West Bank city of Ramallah.

Palestinians regard the declaration as an historical injustice

Everyone puts up a hand.

"Yes," a 15-year-old girl answers. "This declaration was illegitimate because Palestine was still part of the Ottoman Empire and Britain did not control it."

"Britain considered the Arabs as a minority while they formed over 90% of the population."

'Huge hope'

Israeli children, inevitably, tend to see British involvement more positively when they study the Balfour Declaration in a lesson towards the end of their high-school years.

In Balfouria, a village in northern Israel, nine-year-old Noga Yehezekeli is already proudly able to recite a Hebrew version of the text off by heart.

"In the moment it was given, the declaration gave huge hope and a huge push for the Zionist movement," says her father, Neve.

"People saw that if the British government gave such a declaration there was a chance that one day the Jewish nation would be established, which really happened later in '48" - the year the State of Israel was formed.

The declaration gave Zionists huge hope, says Neve Yehezekeli (right)

Residents of Balfouria - including Neve's grandfather - were part of a growing Jewish community in Palestine when Lord Balfour visited in 1925. They gave him a hero's welcome.

By that time, the area was under British administration. The Balfour Declaration had been formally enshrined in the British Mandate for Palestine, which had been endorsed by the League of Nations.

During the first half of the Mandate period, Britain allowed waves of Jewish immigration. But amid an Arab backlash and rising violence, Israelis remember how it later blocked many fleeing persecution, particularly during the Holocaust.

Hard to deliver

At the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, inaugurated by Balfour, Professor Ruth Lapidoth has studied the 67-word document.

An expert on international law, Prof Lapidoth argues it was a legally binding declaration, but says Britain found it hard to deliver on its pledge.

Lord Balfour was given a hero's welcome by the Jewish community in Jerusalem in 1925

"The political situation was very bad when the Nazis came to power and then England needed the help, the friendship of the Arab countries," she says.

"Then they had to limit the implementation of the declaration, which is a pity."

Prof Lapidoth left Germany in 1938, a year before the start of World War Two, and so has a personal interest in the pronouncement.

"I'm still very grateful for it," she says. "It was really the source of our right to come back to Palestine, including my own."

'Long-due promise'

Israel's Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, describes the Balfour Declaration as "a central milestone" in the process of establishing his country.

The British government has invited him to London for events to mark the centenary on Thursday.

That decision, at a time of dimming hopes for Israeli-Palestinian peace, has infuriated Palestinians, who plan a day of protests.

Palestinians say Britain's declaration deprived them of a state

They want Britain to apologise for the Balfour Declaration.

"As the time passes, I think British people are forgetting about the lessons of history," says Palestinian Education Minister Sabri Saidam.

He points out that Palestinians still seek the creation of a state of their own - which alongside Israel would form the basis of the so-called two-state solution to the conflict, a formula supported by the international community.

"The time has come for Palestine to be independent and for that long-due promise to be fulfilled," he says.

- Published31 October 2017

- Published13 October 2023

- Published26 June 2023