MI6's secret 'multi-million pound' Cold War slush fund

- Published

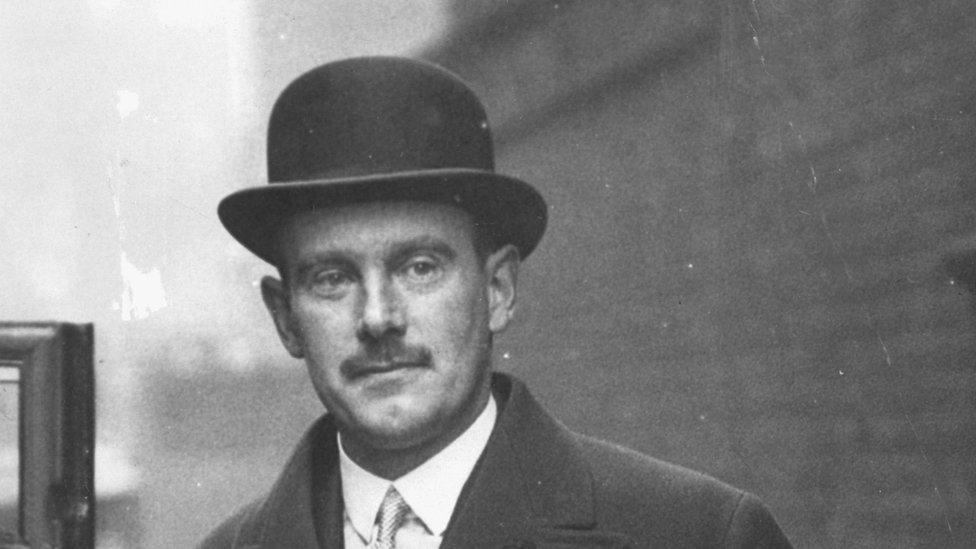

In the late 1940s, a man in late middle age - military bearing, neat moustache, hair balding under his bowler hat - would walk down Whitehall in London to number 22.

Back then it was a bank: a discreet, exclusive establishment for members of the military. The bank's name, Holt's, is still carved in stone above the door, although the building now houses part of the Cabinet Office. The man would give his name as Captain Theo Spencer and withdraw money from one of his accounts.

He would then walk back down Whitehall and head to his office at 54 Broadway. The destination is a clue that his name was not really Captain Theo Spencer.

His office was the headquarters of the Secret Intelligence Service, best known as MI6. The man was Sir Stewart Menzies, the service's chief, often known simply by a single letter: C.

And the newly revealed story of his bank account throws new light on how MI6 worked and also Britain's role in the Middle East.

In a meeting in 1952 with the two most senior officials from the Treasury and the Foreign Office, Menzies offered a confession.

The record of this meeting lies in a remarkable document unearthed in the National Archives by Dr Rory Cormac of the University of Nottingham, and forms the basis for an investigation by BBC Radio 4's investigative history programme, Document.

MI6 archives are closed but the document appears in a file that was declassified as part of a recent release from the cabinet secretary's secret and personal archive.

MI6's then chief, Sir Stewart Menzies, revealed the existence of the secret account in 1952

"He drops a bombshell of an inheritance," Dr Cormac says of the meeting. Since Sir Stewart was about to hand over the reins of MI6 to his successor, there was something he thought officials should know.

For close to a decade he had an account that would become known as the "unofficial reserve", in practice his own, secret slush fund.

Even by the standards of a secret service, the account was remarkably clandestine. No-one knew about it. "Not the Treasury or the Foreign Office. Certainly not ministers. And not even MI6's own finance director," explains Dr Cormac.

At the meeting, the permanent secretary to the Treasury, Sir Edward Bridges, asked Sir Stewart how much money he had in the account and across his reserves, explaining that if it was a substantial sum, that might raise questions of accountability.

MI6 was supposed to be funded by a secret vote of Parliament and under the political control of the foreign secretary.

"The use of such unofficial reserves by 'C' without the prior consent of the Foreign Office, could enable him to carry out policies other than those approved by the Foreign Office and without their knowledge. Clearly this was unlikely to happen, but it would be wrong not to preserve against it," the document records.

Menzies explains that the "unofficial reserve ran to £800,000 but it later emerges this was an underestimate. The actual sum was nearly double, £1.4m, more than £39m in today's money by one estimate.

What was it for? C's answer in 1952 is revealing. "He thought it right to have a large sum to meet such contingencies as (a) a very large inducement to some person in an absolutely key position, or (b) the Vote for the Service being drastically cut in some political emergency in a way which would make it impossible to carry on the Service in the way it was necessary."

Option (a) means an incredibly large bribe for some foreign official, and Option (b) seems to refer to the possibility that politicians might cut MI6's budget, as they did at the end of World War One.

"MI6 were pretty worried lest they might lose their money," explains Gill Bennett, former chief historian at the Foreign Office. "So if they had money from whatever source, in one pocket or another, they really wanted to hang on to it."

The fund seems to be largely the result of an influx of money at the end of World War Two (although the account may date back to MI6's first chief, Sir Mansfield Cumming). The mystery though is where the money came from.

The document records that it was the result of donations from what are called "well-wishers" of the service "including a particularly large sum from an American".

Given the emergence of the Cold War and the fact that the future of America's own intelligence community looked uncertain in 1945, Dr Cormac believes it's possible a well-connected individual could have looked to Britain.

"Maybe this could come from an American who was concerned about future threats and wanted to make sure MI6 were adequately funded in case of emergency."

The revelations from the document do not end there. The files show that in the six years after the civil servants found out about the "unofficial reserve" only a few thousand pounds was being withdrawn each year and it was eventually combined with (smaller) "official" reserves.

Could some of the money for the secret fund have come from the United States?

But the papers also say these reserves were vital in allowing MI6 to carry out a number of operations: it gave the service the latitude to do certain things knowing that it would not run out of money because it knew they had this extra cash in its back pocket.

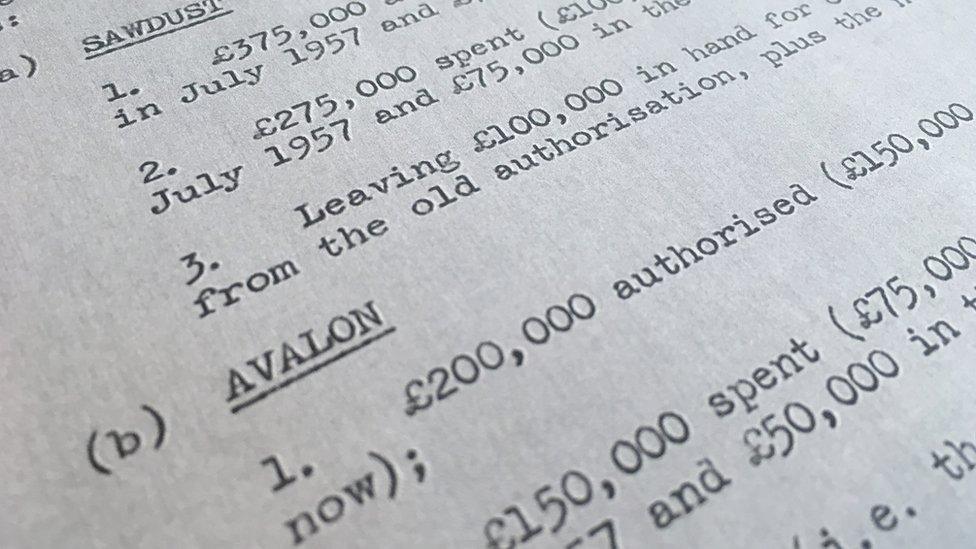

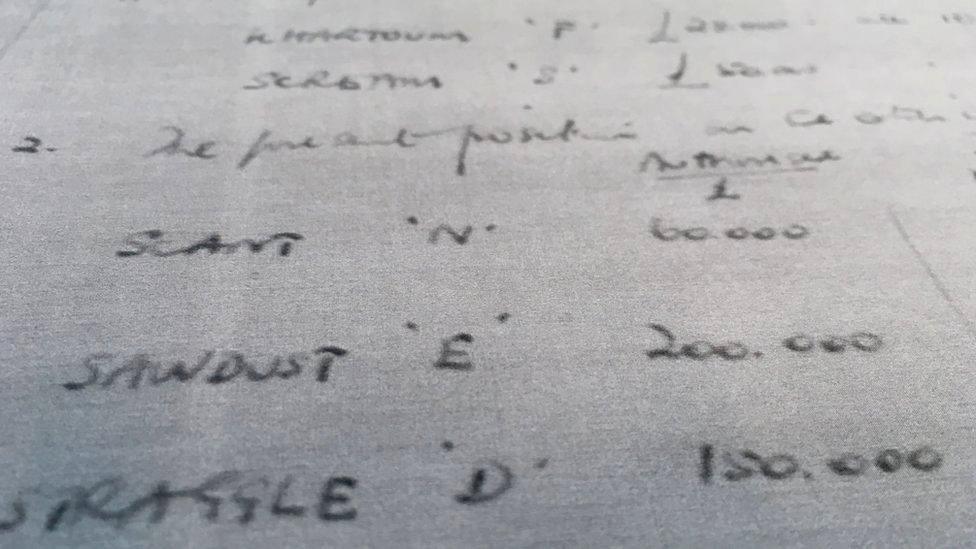

One of the files contains a list of secret operations by codename. Scant, Scream, Sawdust, and Straggle are just four of them, all covert actions in the Middle East. Alongside is the amount spent on each in one year, for instance £200,000 on Sawdust (thought to be operations against President Nasser in Egypt).

Some of these codenames were known about in the past but others are unknown to historians who had studied this period. Helpfully, in some cases someone has actually written in pencil what these codenames refer to.

The operations range across the region, from Sudan to Oman to Lebanon. In some cases, these were propaganda operations but in others, such as Syria, there were plans (never implemented) to assassinate senior officials to bring about regime change.

The documents show that MI6 continued to target Egypt's President Nasser after the 1956 Suez crisis

What is most striking is that many of these operations were running in 1957, a year after Britain's botched invasion of Egypt to try to capture the Suez Canal after it had been nationalised by President Nasser.

"If you add all these up, what you discover is a big increase in the number of special operations post-Suez," says Stephen Dorril, author of MI6: Fifty Years of Special Operations, who reviewed the files. "There had been an idea that Suez dealt a major blow to Britain and MI6 but actually they came back."

"We see operations to subvert Nasser before and after Suez," concurs Dr Cormac.

So do these files show a rogue agency finally being brought to heel by Whitehall? Not quite: they do show MI6 owning up to the secret money and putting it under Treasury supervision.

But they also reveal that, for a few more years after that, the appetite for aggressive covert action was if anything increasing, and with the blessing of officials and very senior ministers.

Today, MI6 says it operates under the law and under careful political and financial controls. But if you are ever in a bank and hear someone ask to make a large withdrawal in the name of a Captain Theo Spencer, then let us know.

Gordon Corera's report, MI6's Secret Slush Fund, is on Document on BBC Radio 4 on at 20:00 GMT on 20 November, and available later via BBC iPlayer.