Yemen: Finding near-famine - and lots of food

- Published

Fruit for sale in a market-place - but few can afford to buy it

How do you explain a famine in a country where there's food?

A couple of years ago I was in Ethiopia, reporting on the threat of famine, in the same place where BBC correspondent Michael Buerk covered the "biblical" famine in 1985.

Those famines, or so-called "parched-earth" famines, sort of make sense. If food doesn't grow because, say the rains have failed, then people starve.

I was in Kenya in 2011, covering a parched-earth famine there too. Catastrophe was compounded by war in both cases - conflict with separatist guerrillas in 1980s Ethiopia and with al-Shabab Islamists more recently in Kenya - but the bottom line was food wasn't growing.

This is different. Welcome to Yemen in 2017. The UN estimates seven million people are facing famine in the Arab world's poorest nation - yet there's no parched earth.

In the frontline city of Taiz, under siege from Houthi rebels for two-and-a-half years, a stroll around one of the local markets reveals abundance. Huge pomegranates and oranges, fresh garlic, bananas, courgettes and tangerines.

There are supermarkets full of produce too - fresh meat, eggs, steaks and ribs. So how on earth can this country be starving? It makes no sense.

Soaring prices

I was shown around one of the markets in Taiz by a man I'd met the day before. Sami Abdul Hadi, 55, saw our team filming outside one hospital.

He introduced himself to us and said we had to make sure our report included the real crime about the conflict in Yemen: people are starving, he said, yet there's plenty of food to go round. So we agreed to meet the next day.

"Look at these fruits," Sami told me, gesturing to a particularly healthy looking pile of oranges.

"Before the war, they were 300 Yemeni rials ($1.2; £0.90), now they're 600. No-one can afford the food here," he said, with a sigh of resignation and a shake of his head.

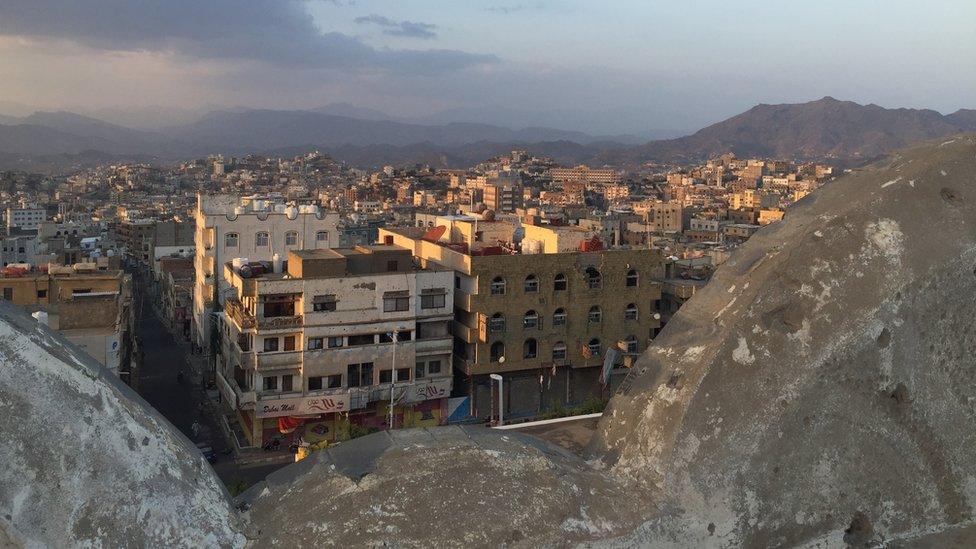

Taiz, Yemen's second city, has been besieged by rebels since 2015

Sami himself couldn't afford the food on display in front of him. A former insurance salesman, he'd been out of work since 2009 and relied on handouts from the World Food Programme.

Finding decent paying jobs, any job in Yemen, is pretty near impossible, in the middle of the war.

Under blockade

As I was talking to Sami, a group of people began to cluster around us.

A man in his 80s said he couldn't get the medicine he needed for his diabetes. Another man lamented the shortage of petrol and fuel. While one man said he hadn't been paid for weeks because of the war.

The BBC's Clive Myrie reports from one hospital on the brink of running out of fuel

Yemen is cursed by man. Its tragedy isn't a failure in nature, but a failure of politics. It's experiencing a political famine.

Before the war 90% of Yemen's food was imported anyway. The prosperity of the nation, and its people, depended on fully functioning seaports, an uncluttered road network and open airspace.

Inside Yemen's industrial-scale prosthetic limb factory

The current conflict means these three things are under strain. Saudi Arabia, which is leading a coalition fighting the Houthis in Yemen, can close the ports at will, making it difficult for food and aid shipments - upon which 21 million people now rely - to get into the country.

That's exactly what the kingdom did on 4 November, after rebels here fired a rocket, at Riyadh International Airport, across the border.

The aid agencies now fear that unless all the ports fully reopen soon, warehouse stocks will run out in the next few months.

Manmade

Yemen's road network is a mess. Some highways and bridges have been destroyed in the war, and convoys of food have to run the gauntlet of rebels, who've been known to hold up lorries, and only send them on to areas sympathetic to their cause.

Lorry drivers also have to worry about routes, that cross-cross territory controlled by al-Qaeda.

All this is what makes Yemen's "famine" manmade and political.

Across Yemen three million people have had to flee their homes

Sami Abdul Hadi, like millions of Yemenis, just cannot quite understand how he got into this mess.

He was educated at the University of Cairo. He has a degree in political science and he speaks good English. Living off handouts from the UN isn't what he expected in his life.

But then, how do you plan for a war that's killed or wounded more than 12,000 people, displaced more than three million, and beggared a nation?

- Published9 November 2017

- Published7 November 2017

- Published6 November 2017

- Published23 August 2017

- Published5 October 2017

- Published14 April 2023