Iran protests: Social media messaging battle rages

- Published

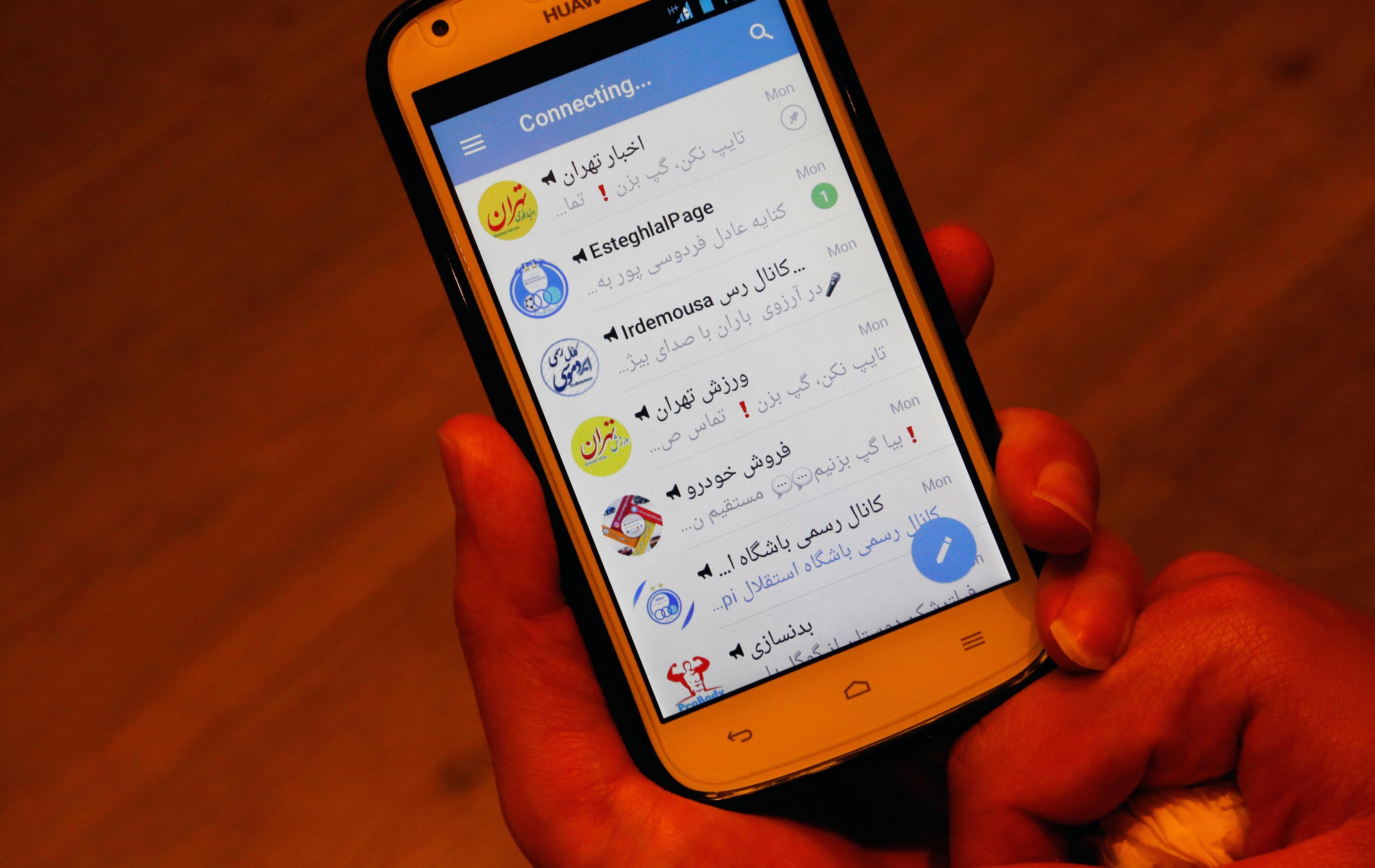

An Iranian user tries and fails to access Telegram after the government blocked the messaging app

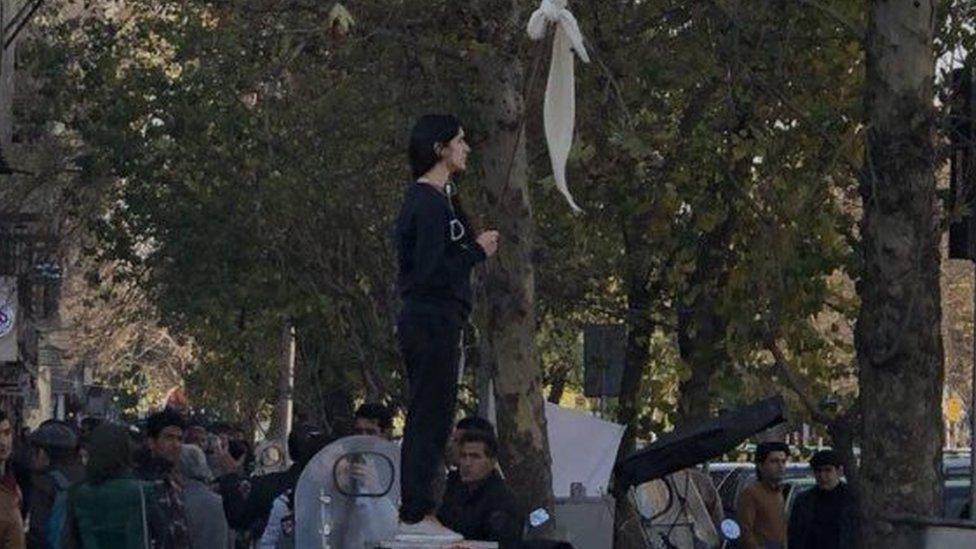

Iran has been rocked by a rare wave of protests over economic hardship and lack of civil liberties for the past week, but streets are not the only battleground between the Islamic Republic and its critics.

A cyber battle on several fronts is being fought between the two sides on social media platforms.

In 2009 - the last time Iran saw demonstrations of such scale - social media was dominated by pro-opposition users and reformists who used Facebook, YouTube and Twitter to share images of the Green Movement to the outside world.

Today, messaging apps are used by a significantly higher percentage of the population and the government is better prepared to confront its opponents on digital media.

Many senior hardline politicians and activists use a variety of platforms on a daily basis - despite some being officially blocked - and boast hundreds of thousands of followers sympathetic to their cause.

After the Stuxnet computer worm hit Iran's nuclear facilities in 2010, the country invested heavily in cyber capabilities and set up a team of trained hackers known as the Iranian Cyber-Army.

Iran protests: Why people have taken to the streets

In the absence of independent news outlets and state TV's typically one-sided coverage, citizens took to social media to share photos and videos of the demonstrations with the aim of disseminating their message and inviting more local residents to join the crowds.

Telegram - which has an estimated 40 million users in Iran, equivalent to almost half the population - has been the platform of choice for the protestors.

In response, the officials "temporarily" blocked Telegram and Instagram. Facebook, YouTube and Twitter have been banned since 2009.

'Nothing going on'

But proponents of the Islamic Republic did not leave the social media battleground to the critics this time.

One of the notable tactics used was the creation of dozens of Twitter bots whose job ranged from calling widely shared videos of rallies fake to discouraging potential protesters from joining rallies.

A social bot automatically generates content and followers, mostly to support a wider campaign.

Most of these accounts have unusual profile names and pictures, external, and were created during the protests.

The accounts have no more than a handful of followers, which happen to be similar bot accounts.

In a seemingly co-ordinated campaign, a group of bot accounts attempt to play down the scale of unrest and dissuade further protesters from joining rallies

"I just arrived here, there is nothing going on," posted one account, external in response to a video about an alleged protest in Rasht, Gilan province.

"Why are you lying? No-one is here," said another.

The exact same messages by the same accounts can be seen below many videos shared between 1 and 4 January.

While clearly co-ordinated, there is no evidence that these accounts were created by official authorities or security services.

Bot-spotting tips

The Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRL) offers social-media users tips for spotting a bot:

Frequency: Bots are prolific posters. The more frequently they post, the more caution should be shown. The DFRL classifies 72 posts a day as suspicious, and more than 144 per day as highly suspicious.

Anonymity: Bots often lack any personal information. The accounts often have generic profile pictures and political slogans as "bios".

Amplification: A bot's timeline will often consist of re-tweets and verbatim quotes, with few posts containing original wording.

Common content: Networks of bots can be identified if multiple profiles tweet the same content almost simultaneously.

The full list of tips on spotting bots can be found here, external.

Hashtag wars

At the same time, hardline users began an initiative to enlarge and highlight the faces of protesters captured in videos and pictures, calling for the intelligence agencies to identify and arrest them. Tasnim news agency, affiliated to the powerful Revolutionary Guards, was among those joining the initiative, external on Twitter.

The protesters hit back immediately. They set up a Twitter account sharing the alleged names and details of security personnel, external confronting the demonstrators. In addition, they identified the accounts highlighting individual protesters and repeatedly reported them to Twitter, external.

The protests in Iran attracted an usually large number of tweets from Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arab world in favour of the demonstrators

The hashtag mostly associated with the recent events in Iran, #nationwide_protests, has been used more than 470,000 times so far.

But an analysis of the hashtag shows a large number of posts in favour of the demonstrations from Saudi Arabia.

Some supporters of the Islamic Republic and conservative agencies have been using their own hashtag, #nationwide_riots.

An analysis of the main hashtag of the protests shows a large number of tweets originating from Iran's regional rival Saudi Arabia

Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shia Iran are regional rivals and have been involved in proxy wars in the Middle East, notably in Syria and Yemen.

An Arabic hashtag, #happening_now_in_Iran, has been used more than 66,000 times since the first day of the protests.

By BBC UGC and Social News Team

- Published6 January 2018

- Published4 January 2018

- Published2 January 2018

- Published4 January 2018

- Published3 January 2018

- Published14 October 2024