Iran nuclear: What's changed after Netanyahu's presentation?

- Published

Stark revelations, or political theatre?

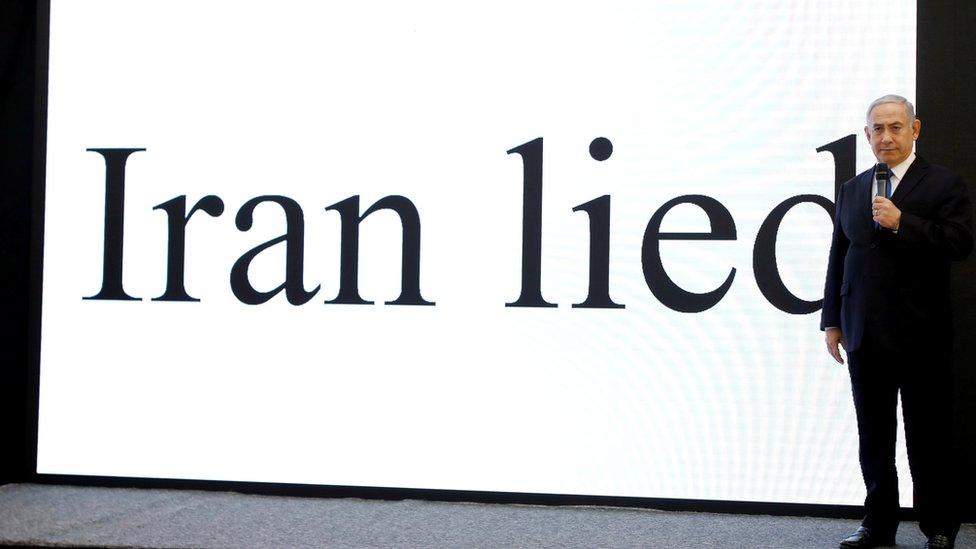

So what has changed, if anything, in the wake of the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's theatrical presentation of Israel's claimed seizure of a trove of documents from Iran's secret nuclear archive?

The purpose and timing of Mr Netanyahu's presentation was clear: to discredit the Iran nuclear deal, and to influence one man - Donald Trump.

The US president must decide by mid-May whether to walk away from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), or to stick with it, at least for the time being.

So what did Mr Netanyahu actually tell us?

It was in large part a reminder that Iran, despite all its denials, did have elements of a nuclear weapons programme and that it retains the scientific know-how to reactivate such a programme if it ever wanted to.

That of course is not news to the major powers who signed up to the nuclear deal with Iran. Indeed, it was why they sought a nuclear agreement with Tehran in the first place.

Benjamin Netanyahu's argument was clear

What Mr Netanyahu gave was essentially a history lesson. He did not show any convincing evidence that Iran is in breach of the 2015 agreement. And this could prove crucial.

Indeed, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) - the global nuclear watchdog monitoring the deal - has given Iran a clean bill of health on several occasions. It is, apparently, upholding its end of the agreement to the letter.

Those governments like Britain, France and Germany who have been urging Mr Trump to maintain the deal with Tehran will argue that Mr Netanyahu's case, far from undermining the JCPOA, actually underscores why it is necessary.

Gathering war clouds

Mr Netanyahu, like Mr Trump, has long been opposed to the JCPOA.

Mr Trump insists that it is "a bad deal", though the fact that it was negotiated by his predecessor Barack Obama seems to weigh heavily in the president's judgement.

Mr Netanyahu believes that it does not go far enough in ending Iran's nuclear ambitions, and that once many of its clauses expire Iran will have the know-how, enrichment capability and missile programme to develop a nuclear arsenal at relatively short notice if it so wishes.

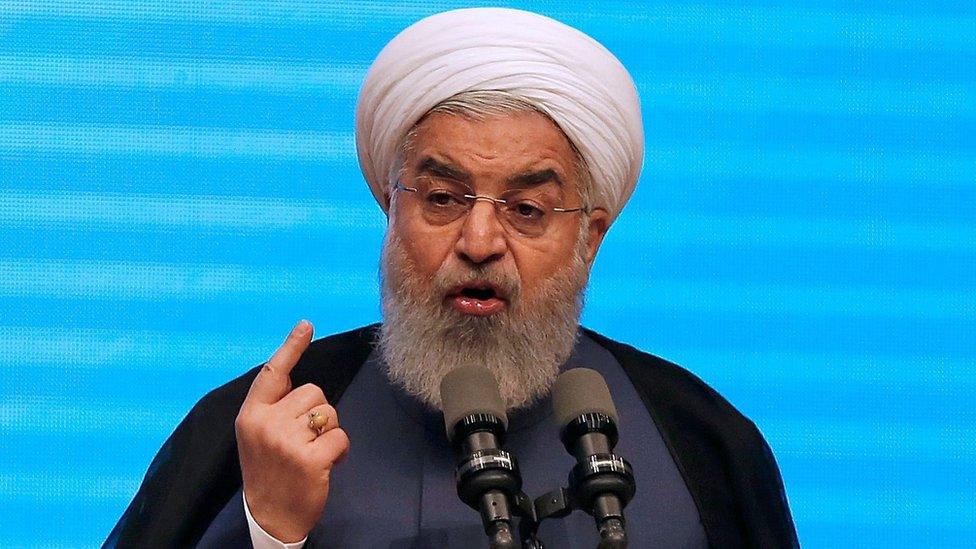

President Trump has long criticised the Iran deal, while Mr Netanyahu wants to end it

Israel's position is complicated by the fact that it is involved in a developing conflict with Iran which has a growing influence in Syria, where Tehran has strongly backed the Assad regime. Iran supplies weaponry to Hezbollah in southern Lebanon, much of which is routed through Syria.

War clouds are gathering and Mr Netanyahu wants the JCPOA gone.

The problem is that supporters of the agreement insist that precisely because of these growing tensions any constraint on Iran's nuclear activities is a good thing and should be maintained.

And Mr Netanyahu must contend with the fact that many senior Israeli military and security figures, while not enthusiastic about the JCPOA, also believe it is better to keep it than consign it to the waste bin.

Europe vs Trump

So whatever the theatricality of Mr Netanyahu's presentation not much has really changed. The Iran nuclear deal stands on its merits (or shortcomings) and President Trump must now work towards his own conclusion.

Will he be swayed by the Israeli prime minister - whose views are more in tune with his own? Or will he give ground to the key European signatories of the agreement - France, Britain and Germany - who all want to see the deal kept in place?

Boris Johnson on Iran nuclear deal: 'I don't think anybody has come up with a better idea'

The Europeans also believe, like President Trump, that something needs to be done to expand the JCPOA's scope.

But there is a paradox here. By agreeing with Mr Trump that an additional deal is required to cover things like Iran's missile programme and its wider regional activities, might the Europeans actually be undermining the very agreement that they want to save?

The JCPOA covers what it covers and no more. If the original negotiators had tried to expand its scope they would probably have met a brick wall from the Iranians.

What's clear is that whatever evolving agreement there may be between the European capitals and Washington for further constraints on Tehran, there is no chance of the Iranian government being willing to accept them.

Hassan Rouhani has warned of "severe consequences" if the US reimposes sanctions

The whole purpose of the JCPOA, to use an inelegant term, was to "kick the can down the road" - to postpone any Iranian nuclear crisis for the future.

It set as many constraints on Iran's nuclear activities as feasible while leaving in place a reinforced inspection and verification scheme that may provide some early warning going forward of any efforts by Tehran to break out and rush for a bomb.

The deal can be criticised on many grounds. But it is what was possible at the time. The real question is whether, amidst the worsening tensions in the region, it is better to stick with the agreed constraints or abandon them altogether?

Iran originally signed the deal with the US, UK, France, Germany, China and Russia back in 2015

Mr Netanyahu disagrees with most of the major powers and with large parts of his own security establishment.

He might argue that he and his country are much closer to the epicentre of crisis and that Iran - via its military presence or those of its proxies in Syria and Lebanon - is close to posing a direct threat on Israel's own borders.

Mr Netanyahu is ranged against pretty well all of those who actually signed the deal. President Trump now has the casting vote.

- Published26 April 2018

- Published15 December 2015

- Published25 April 2018

- Published11 January 2018

- Published9 April 2018