Reality Check: The numbers behind the crackdown in Turkey

- Published

Who's been affected by Turkey's state of emergency?

Almost two years after a failed military coup in Turkey, the country remains under a state of emergency. What has happened during the crackdown?

Turkey is holding presidential and parliamentary elections on 24 June. There will be a second-round run-off for the presidency on 8 July if no candidate wins more than half the vote in the first round.

The state of emergency does not prevent registered political parties from taking part in the elections, and all parties are holding rallies and running campaigns.

But the government has used emergency powers to close down many independent media in the last two years, and most television coverage of the election focuses on President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

So why is the state of emergency in place and how many people has it affected?

It was imposed in response to an attempted military coup in July 2016. The coup was a massive shock to Turkey. Parliament in Ankara was bombed by military aircraft, and more than 250 people were killed and 2,200 injured, many on the streets of Istanbul.

Once it was clear that the coup had failed, a state of emergency was declared and the government began one of the largest recent purges of public employees anywhere in the world.

The aim was to remove from office anyone suspected of having links with those who had tried to overthrow an elected government.

The BBC asked a series of questions to the Turkish Ministry of Justice about the state of emergency and the number of people affected by it, but had received no response by the time this article was published.

The figures used here come from a variety of sources: publicly available government information and data from non-governmental organisations.

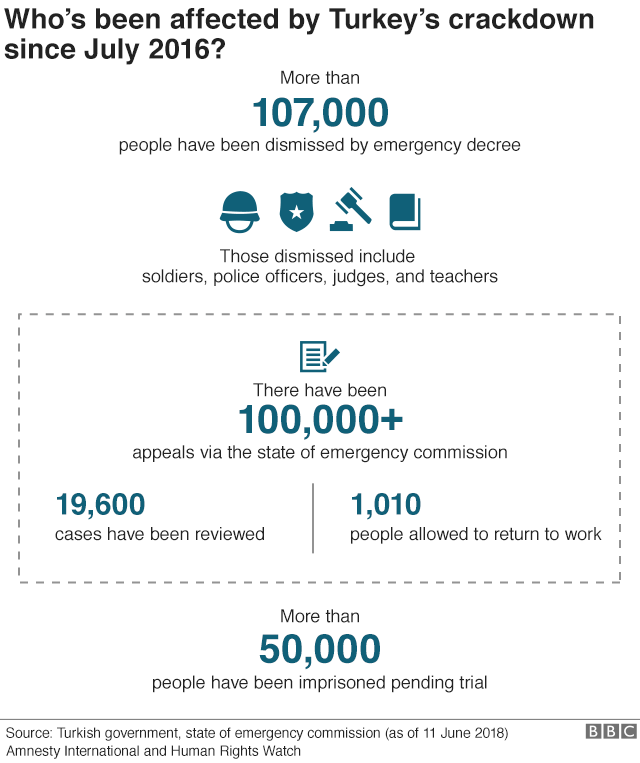

Since July 2016 more than 107,000 people have been removed from public sector jobs by emergency decree. Tens of thousands of others have been suspended, but most of them have subsequently been reinstated after investigation.

There have also been a large number of dismissals in the private sector, but precise numbers are hard to come by.

Many - but by no means all - of those dismissed are alleged to be supporters of the exiled Islamic cleric Fethullah Gulen, who lives in the United States and is a former ally of Mr Erdogan. Turkey accuses Mr Gulen and his followers of organising the coup, but he denies it.

There is no question, though, that tens of thousands of his followers have found jobs in all parts of the state bureaucracy over a period of many years.

Election rallies for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan are drawing large crowds

Among those dismissed by decree since the coup attempt are soldiers and police officers, judges and prosecutors, doctors and teachers.

Approximately a quarter of all judges and prosecutors have been removed from their posts. And a report on the state of emergency issued by the main opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) says at least 5,000 academics and more than 33,000 teachers have also lost their jobs.

Aynur Barkin, a primary school teacher, is one of those who has lost her job. She insists that she has nothing to do with the Gulen movement. She's been taking part in small protests, organised by the Union of Education Workers, of people demanding their jobs back.

"I've been a teacher for 15 years," she says. "My place is in my classroom. I should be able to go back to my school. I should be able to get my job back."

More than 250 people died in the 2016 coup

Initially there was no way of appealing against dismissal by emergency decree. But under pressure from the Council of Europe, which monitors human rights, the government set up a commission to look at individual cases.

More than 100,000 people have appealed to the commission, but it is an administrative process rather than a legal one. The government says it has reviewed 19,600 cases so far, and 1,010 people have been given permission to return to work.

People who have been sacked by decree are given no information initially about what they are alleged to have done wrong. But some reasons are given subsequently, if an appeal to the commission is rejected.

Critics say the evidence is often circumstantial: where you held a bank account, which app you used on your smartphone, or where your children went to school. (Among other things, Gulenist organisations operated banks and a well-established network of schools across the country.)

But the only people who have precise details of the cases against them are those who have been arrested and charged with offences.

More than 50,000 people have been imprisoned pending trial since July 2016.

Imprisoned presidential candidate Selahattin Demirtas appears on photographs at rallies held by his supporters

Again, many of them are alleged supporters of Mr Gulen. Others are leftists or Kurdish activists, also accused of supporting terrorism and imprisoned as part of a broader crackdown on dissent.

Among them is the Kurdish politician Selahattin Demirtas, who is running for president from his prison cell. On Sunday night he made his only TV appearance of the campaign so far, filmed inside Edirne prison. But he often appears at election rallies as a cardboard cut-out.

A large number of human rights activists, lawyers and journalists are also behind bars.

The Turkey-based Platform for Independent Journalism runs a website, external which lists more than 150 journalists and media workers who have been detained or imprisoned since July 2016 and are currently still in jail.

On a visit to London, Mr Erdogan was keen to draw a distinction between "journalists" and "terrorists"

Mr Erdogan was questioned about the jailing of journalists during a joint press conference in London last month with the UK Prime Minister Theresa May. His response was typically robust.

"You have to make a distinction between terrorists and journalists," he said. "Are we supposed to call them journalists just because they carry credentials and ID cards?"

Lifting the state of emergency would not automatically free anyone from prison, nor would it invalidate emergency decrees that have the force of law.

But it would remove a major cause of uncertainty in Turkey, where badly-needed foreign investment fell since the coup took place. In an election in which the state of the economy is the biggest issue, that matters.

Opposition presidential candidates have always said that their first job after the election, if they win, will be to end the state of emergency.

The president has previously insisted that the state of emergency will remain in place while there is a significant threat of "terrorism" from supporters of Mr Gulen or anyone else.

But, in the last few days, Mr Erdogan has changed his tune, suggesting that he too will lift the state of emergency if re-elected - although he has also warned that it could be reimposed if necessary.

Promises made during an election campaign are not always kept once the voting is over.

But it seems that the president may be feeling the pressure.

- Published15 June 2018

- Published16 July 2016