Ending Yemen’s never-ending war

- Published

"Some people say we are in a hurry," says Martin Griffiths, the UN's special envoy for Yemen. "I plead guilty to the charge."

"The people of Yemen have suffered quite enough. It's time."

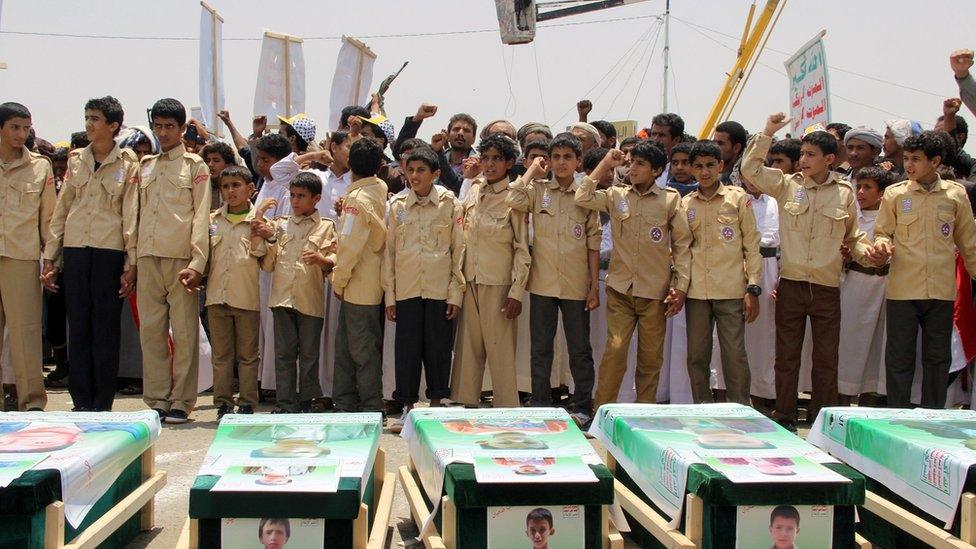

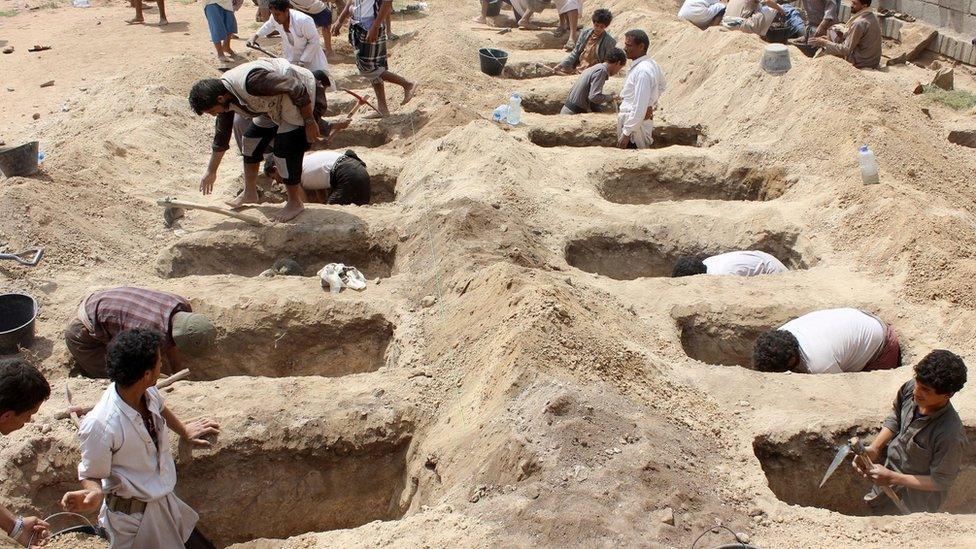

An air strike two weeks ago that took the lives of 44 schoolboys on a field trip, shocking even in a nation shattered by years of strife, has focused minds again on the urgent need to end a conflict that has led to the world's greatest humanitarian crisis.

Mr Griffiths has now sent formal invitations to the warring parties to attend a new round of consultations in Geneva on 6 September. They will be the first talks in two years, after two failed rounds.

UN envoy Martin Griffiths says that if peace efforts in Yemen fail, the world could be looking at “Syria-plus".

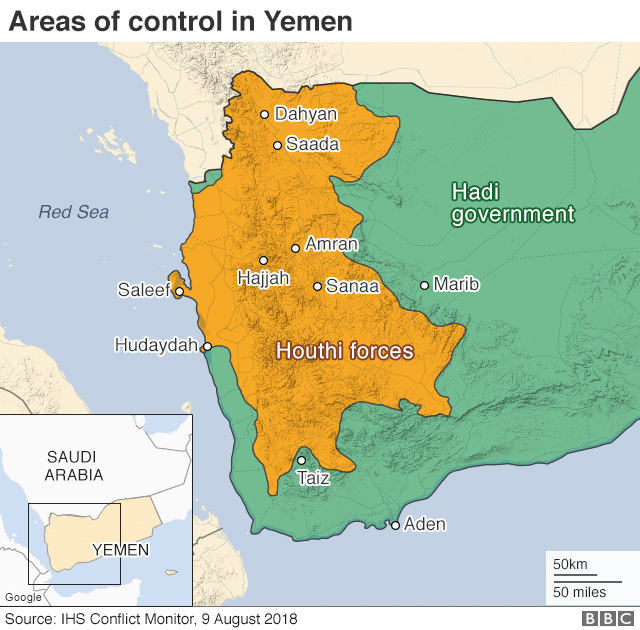

"The good news is, the government of Yemen wants to do this. And the Ansar Allah leadership does too," he says, using the official name of the rebel Houthi movement that took control of the capital Sanaa in 2014 and forced President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi to flee abroad the following year.

Yemen's government has been backed militarily since March 2015 by a coalition of Arab states assembled by neighbouring Saudi Arabia to oust the Houthis, who are aligned to its arch-rival Iran.

This punishing proxy war in the region's poorest nation has ground on, dragging Yemen to the brink of collapse.

The deadly Saudi-led coalition air strike on the bus in the rebel-held northern village of Dahyan on 9 August has threatened to derail a fragile political process fraught with risk.

The Saudi-led coalition says it is investigating the reports of "collateral damage" in Dahyan

Mr Griffiths, who took on his new role in March, is the third UN special envoy since 2011, when an Arab Spring uprising forced long-time leader Ali Abdullah Saleh to hand over power to Mr Hadi.

"There's anger and defiance," explains one official closely involved in the UN's new effort to find a negotiated solution to Yemen's appalling plight. "The Houthis have been threatening not to attend because they fear the investigation into this attack will not be credible."

Images of bloodied schoolboys, bright blue Unicef schoolbags still on their backs, sparked an international outcry and a call by the UN Security Council for a "credible and transparent" investigation.

Fifty-five people were killed in all, and many more injured, when a bomb struck the school bus as its driver stopped to buy snacks at a bustling market.

Aftermath of an attack that shocked the world

A coalition military spokesman initially said its forces attacked a "legitimate military target" after debris from a Houthi missile intercepted over southern Saudi Arabia killed one person and injured 11 others.

Now, the coalition has said it is investigating the reports of "collateral damage" and will compensate victims if necessary.

This latest tragedy has also reignited public criticism over the role of Western countries, including the UK and US, which are backing the coalition through billions of dollars in arms sales and operational support.

The bomb deployed in the latest devastating attack which pulverised the school bus was reportedly provided by a US arms manufacturer.

"The bus attack will certainly add to pressure on Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to move toward a negotiated end to the war," assesses Joost Hiltermann of the International Crisis Group. "But I'm not convinced that this will be decisive."

Earlier this year, Mr Griffiths' sustained shuttle diplomacy and the anguished appeals of aid agencies averted an all-out assault by pro-government forces on the vital Red Sea port of Hudaydah, and the adjacent city, currently in Houthi hands.

Most of the humanitarian aid on which 80% of Yemenis rely for survival comes through Hudaydah.

But it also convinced the UAE, which took the lead on the Hudaydah offensive, that only a ratcheting up of military pressure would bring Houthi leaders to the negotiating table, ready to do a deal.

Under greater threat, Houthi leaders had told Mr Griffiths they were prepared to hand over Hudaydah port to UN administration, a move they had resisted for years. Then the coalition shifted the goalposts. They demanded rebels withdraw from the city too.

Hudaydah's port is the principal lifeline for just under two-thirds of Yemen's population

"We think more military pressure still needs to be exerted on the Houthis," insists an Arab official in the coalition, underlining that victory in Hudaydah would be a game-changer that would bring a swift end to this war.

But the assault against such a large city, where well-trained Houthi fighters are now entrenched, has also proven to be far more daunting than the first coalition military plans envisaged.

"The UAE and its allies have come to realise just how much it will cost them in blood and treasure, as well as in how they'll be viewed," comments one observer.

A diplomatic source says that, in June, as the first onslaught on Hudaydah loomed, then UK Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson called UAE diplomats to urge them to give Mr Griffiths more time to come up with a negotiated solution. Mr Johnson is said to have warned of another Stalingrad - an allusion to shocking images of destruction in World War Two.

Eight million Yemenis do not know how they will obtain their next meal

Ever since the UN envoy first announced his plan to launch a new political process, all sides have expressed support for his efforts. But they have voiced pessimism too.

And while the US and UK governments are known to raise concerns about coalition military tactics in private with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, in public they defend their long-standing allies.

"There's a strong impression that they support the man, but not the plan," is how a Western Yemen expert puts their approach to Mr Griffith's mission.

"That's them having their cake and eating it too," he explained. "They say: 'We totally want Martin to create peace, but if his plan upsets our partners, we're not going to push.'"

Iran's role is also a factor. But the extent of its military support, and its sway over the Houthis, is disputed.

"The Iranians play a role in allowing the Houthis to believe they can hold out," says Mr Hiltermann. "But the Houthis have shown in the past that the Iranians don't have that much influence over them."

Saudi Arabia and its allies see the Houthis as an Iranian proxy

The bar has deliberately been set low for this next round of talks in Geneva. But some observers see rare glimmers of hope.

"There's fatigue," points out one analyst following the process closely. "Yemenis are exhausted by this conflict."

And the arrival of the experienced, plain-speaking UN mediator has translated into enhanced access in all capitals, including meetings with senior Houthi leaders.

"The Houthis are now willing, and not afraid, to make concessions they weren't a year ago including on Hudaydah," a Yemen expert added.

Sources say the rebel leaders have made new offers, including a proposal to freeze the fighting, as well as alternative arrangements for Hudaydah city.

The UN says 6,590 civilians have been killed and 10,470 injured in Yemen since 2015

Geneva will only be talks about talks, an informal discussion only among Yemenis.

The ambition is to move gradually towards more substantive negotiations in a broad process that draws on dialogue in backchannels, shuttling between capitals, and engagement with Yemenis across civil society.

Mr Griffiths describes the goal as a "transitional political operation under a national unity government... and security arrangements for the withdrawal of all armed groups."

"Baby steps, just baby steps," is the phrase used by Bashraheel Hisham Bashraheel, deputy editor-in-chief of Al-Ayam newspaper in the southern Yemeni city of Aden, which is under government control.

Like baby steps, there's a great risk this new process will falter - just like the last two rounds.

"Geneva will be a beginning," says Mr Griffiths. "Even a beginning is good."

- Published22 August 2018

- Published13 August 2018

- Published10 August 2018

- Published9 August 2018

- Published13 June 2018