IS 'caliphate' defeated but jihadist group remains a threat

- Published

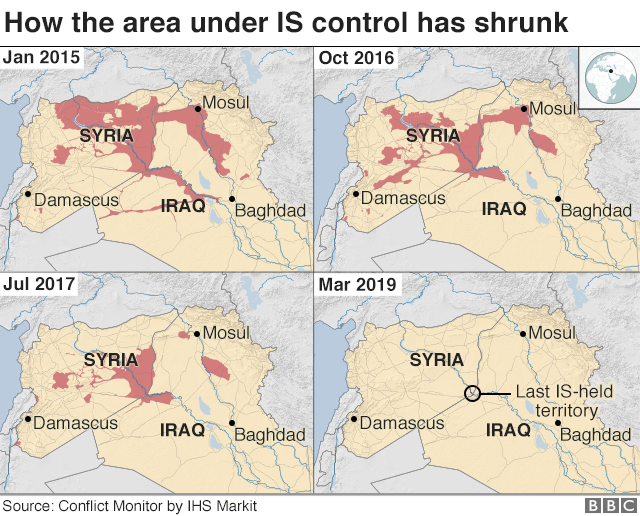

A US-backed alliance of Syrian fighters has announced that the jihadist group Islamic State (IS) has lost the last pocket of territory in Syria it controlled, bringing a formal end to the "caliphate" it proclaimed in 2014.

IS once controlled 88,000 sq km (34,000 sq miles) of territory stretching from western Syria to eastern Iraq. It imposed its brutal rule on almost eight million people, generating billions of dollars in revenue from oil, extortion, robbery and kidnapping.

Despite the demise of its physical caliphate, IS remains a battle-hardened and well-disciplined force whose "enduring defeat" is not assured.

The head of the US military's Central Command, Gen Joseph Votel, said in February that it was necessary to maintain "a vigilant offensive against the now largely dispersed and disaggregated [IS] that retains leaders, fighters, facilitators, resources and the profane ideology that fuels their efforts".

Iraqi government forces recaptured the city of Mosul in July 2017

And if pressure on the group is not sustained, IS "could likely resurge in Syria within six to 12 months and regain limited territory in the Middle Euphrates River Valley", external, military officials told the US Department of Defense Office of the Inspector General in January.

Such warnings appeared to persuade Mr Trump not to withdraw all of the 2,000 US troops from Syria, as he had promised in an announcement in December 2018. That plan prompted the resignation of Defence Secretary Jim Mattis and alarmed allies in the Global Coalition to Defeat IS.

The White House said in February that it would leave 400 "peacekeepers" in Syria for a "period of time", external, 200 of which would be based at the al-Tanf outpost, at the intersection of the Syrian, Jordanian and Iraqi borders.

What next for IS?

In Iraq, where the government declared victory in December 2017, the jihadist group has already "substantially evolved into a covert network", external, UN Secretary General António Guterres said in a report to the Security Council released in February.

"It is in a phase of transition, adaptation and consolidation. It is organising cells at the provincial level, replicating the key leadership functions," he added.

IS sleeper cells in Iraq have attacked civilian and government targets

IS militants are active in rural areas with remote, rugged terrain that gives them freedom to move and plan attacks. These include the deserts of Anbar and Nineveh provinces, and the mountains that straddle Kirkuk, Salah al-Din and Diyala provinces.

Cells "appear to be planning activities that undermine government authority, create an atmosphere of lawlessness, sabotage societal reconciliation and increase the cost of reconstruction and counter-terrorism", according to Mr Guterres. These activities include kidnappings for ransom, targeted assassinations of local leaders, and attacks against state utilities and services.

The IS network in Syria is expected to evolve to resemble that in Iraq.

Besides the Euphrates valley, the group has a presence in the opposition-held north-western province of Idlib, in government-held areas south of the capital Damascus, and in the Badiya region, a vast stretch of desert in south-eastern Syria.

The US military helped Kurdish-led forces drive IS out of north-eastern Syria

The militants have access to heavy weapons, and are able to carry out bombings and assassinations throughout the country, according to the US defence department's inspector general. Their leaders also retain "excellent command and control capability".

The location of the group's overall leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, is not known. But he has eluded being captured or killed, despite having fewer places to hide.

IS continues to generate revenue through criminal activities. It also receives external donations and is estimated to have between $50m and $300m (£39m-231m) in cash.

How many militants are left?

IS has suffered substantial losses, but Mr Guterres said it still reportedly controlled between 14,000 and 18,000 militants in Iraq and Syria, including up to 3,000 foreigners.

The US Special Envoy to the Global Coalition To Defeat IS, James Jeffrey, said in mid-March that Washington believed there were still between 15,000 and 20,000 IS "armed adherents active" in the region, external, many of them in sleeper cells.

The US defence department's watchdog was told by the Global Coalition in July 2018 that there were between 15,000 and 17,000 IS militants in Iraq and between 13,000 and 14,000 in Syria. However, US commanders subsequently said they did not have a lot of confidence in those figures.

IS was driven out of Raqqa, the de facto capital of its "caliphate", in October 2017

The SDF has captured about 1,000 foreign IS fighters. Hundreds of women and more than 2,500 children associated with foreign fighters are meanwhile living in camps for displaced people in SDF-controlled areas. There are also reported to be about 1,000 foreign fighters in detention in Iraq.

The US has called for the repatriation of the SDF's captives for prosecution. But their home countries have raised concerns about bringing hardened IS members back and the challenges of gathering sufficient legal evidence to support prosecutions.

Up to 40,000 foreigners are estimated to have travelled to fight in Syria and Iraq in total.

IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has eluded being captured or killed

The actual number of people still making the journey is unknown, but the flow has reduced significantly. The Global Coalition estimated that it was "most likely 50 per month".

The net flow of foreign fighters away from Iraq and Syria is also said to be low. As of October 2017, more than 5,600 had returned to their home countries, external.

Meanwhile, there are significant numbers of IS-affiliated militants in Afghanistan, Egypt, Libya, South-East Asia and West Africa, and to a lesser extent in Somalia, Yemen, Sinai and the Sahel.

Individuals inspired by the group's ideology also continue to carry out attacks elsewhere.

IS exploited chaos and divisions

IS grew out of al-Qaeda in Iraq, which was formed by Sunni Arab militants after the US-led invasion in 2003 and became a major force in the insurgency there.

In 2011, the group - now known as Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) - joined the rebellion against President Bashar al-Assad in Syria, where it found a safe haven and easy access to weapons.

At the same time, it took advantage of the withdrawal of US troops from Iraq, as well as widespread Sunni anger at the sectarian policies of the country's Shia-led government.

In 2013, ISI began seizing control of territory in Syria and changed its name to Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Isis or Isil).

The following year, Isis overran large swathes of northern and western Iraq, proclaimed the creation of a "caliphate", and became known as "Islamic State".

A subsequent advance into areas controlled by Iraq's Kurdish minority, and the killing or enslaving of thousands of members of the Yazidi religious group, prompted a US-led multinational coalition to begin air strikes on IS positions in Iraq in August 2014.

A global campaign

The battle to push IS out of Iraq and Syria has been bloody, with thousands of lives lost and millions of people forced to flee their homes.

In Syria, troops loyal to President Assad have battled the jihadist group with the help of Russian air strikes and Iran-backed militiamen. The US-led coalition has meanwhile supported the SDF, an alliance of Syrian Kurdish and Arab fighters, and some Syrian Arab rebel factions in the southern desert.

In Iraq, local security forces have been backed by both the US-led coalition and a paramilitary force dominated by Iran-backed militias, the Popular Mobilisation.

The US-led coalition, which included forces from Australia, Bahrain, France, Jordan, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and the UK, began launching air strikes against IS targets in Iraq in August 2014. The coalition's Syrian air campaign began a month later.

Since then aircraft deployed as part of the coalition's Operation Inherent Resolve have carried out more than 33,000 air strikes.

Russia is not part of the coalition, but its jets began air strikes against what it called "terrorists" in Syria in September 2015 to bolster the government of President Assad.

The Russian defence ministry reported in August 2018 that its forces had flown 39,000 sorties in Syria since 2015, destroying 121,000 "terrorist targets" and killing more than 5,200 members of IS.

Key cities were recaptured

Early progress in the US-led coalition's campaign against IS included the recapture of the city of Ramadi, the capital of Anbar province in Iraq, by Iraqi pro-government forces in December 2015.

The US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces alliance has driven IS out of north-eastern Syria

The recapture of Iraq's second city of Mosul in July 2017 was seen as a major breakthrough for the coalition, but the 10-month battle left thousands of civilians dead, with more than 800,000 others forced to flee their homes.

In October 2017, the Syrian city of Raqqa, so-called capital of the self-styled "caliphate", was re-taken by the SDF with coalition air support, ending three years of rule by IS.

The following month, the Syrian army regained full control of the eastern city of Deir al-Zour, and Iraqi forces retook the key border town of al-Qaim.

Many thousands have been killed

Exact numbers of the casualties for the war against IS are not available.

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a UK-based monitoring group, has documented the deaths of 371,000 people, including 112,600 civilians, in Syria since the civil war began in 2011.

The UN says at least 30,912 civilians were killed in acts of terrorism, violence and armed conflict in Iraq between 2014 and 2018. But Iraq Body Count, external, an organisation run by academics and peace activists, puts the civilian death toll at more than 70,000.

Millions have been displaced

At least 6.6 million Syrians have been internally displaced, while another 5.6 million have fled abroad - more than 3.5 million of them have sought refuge in Turkey, and almost one million in Lebanon and almost 700,000 in Jordan.

Many Syrians have sought asylum in Europe, with Germany taking the greatest number.

In Iraq, the number of displaced people has fallen below two million for the first time since December 2013.

Some Syrian refugees from areas previously held by IS have sought asylum in Europe

By September 2018 the International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimated nearly four million people had returned home.

But the UN reports that a lack of jobs and destruction of property and limited access to services are still preventing many people from returning to their homes.

- Published22 October 2018

- Published2 May 2023

- Published10 July 2017

- Published28 March 2018