Who will help rebuild the city of Raqqa?

- Published

A Syrian family's return to Raqqa after five years of struggle

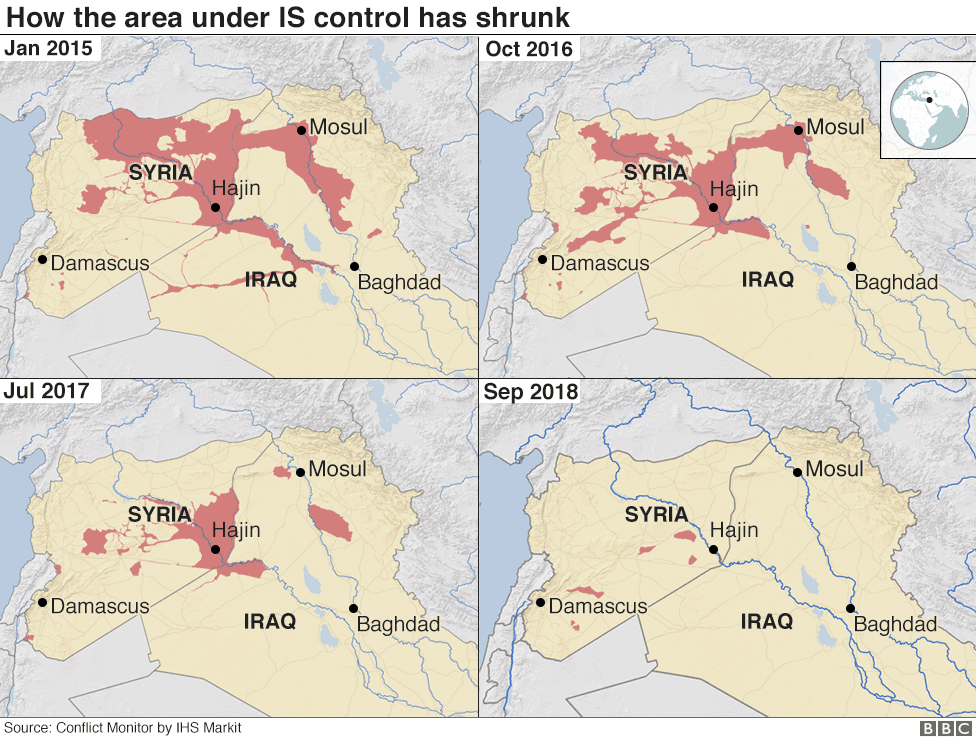

It's a year since the Syrian city of Raqqa was freed from the grip of the group known as Islamic State. Evidence of the brutal battle to dislodge the extremists is visible everywhere you look. But the fear of the people who've returned to this broken city is that the rest of the world is now walking away.

Raqqa is still a rubble city. The chaos is ultimately the creation of IS. But the devastation was also caused by thousands and thousands of coalition airstrikes.

It took more than five months of intensive bombing to dislodge the extremists from their de facto capital. Mostly dropped from US warplanes but British ones too.

Yet neither Britain nor America appears willing so far to take responsibility for repairing the damage they caused.

Despite the devastation, many families who fled the fighting have now returned. Some shops have re-opened. Traffic runs past the rubble piled high on the side of the streets. But they are now asking who will rebuild their shattered city?

We were driven around Raqqa by US special forces in unmarked armoured 4x4 vehicles. Some children waved at the convoy as we passed. The US commander in the front seat, who we can't identify, told me: "There's still a tonne of goodwill." The danger is that any goodwill will evaporate the longer their needs go unmet.

We were taken to meet Raqqa's Civil Council which has a long list of concerns that need to be addressed. Much of the city is still without essential services such as running water and electricity.

None of Raqqa's destroyed bridges, essential for the movement of goods and people, has been repaired. The main hospital where IS made their last stand still lies in ruins.

Council member Layla Moustaffa says: "We're concerned about how long it's taking for the international community to respond." She likens Raqqa to a sick man in urgent need of medical attention.

Ammar Jabor, another council member, says he believes "everyone who contributed to the destruction of the city should help rebuild it". When I ask who, he replies: "I'm asking the USA and the UK to rebuild this beautiful city."

Raqqa Civil Council member Layla Moustaffa is concerned at the international response to the situation in the city

America and Britain may have contributed to the devastation. But both have stated they won't get involved directly in efforts to rebuild those areas of Syria that have been destroyed by the war until there's a UN-backed peace process for the whole country. That doesn't look like happening anytime soon.

Instead the US and a handful of other nations say they're focusing their efforts on "stabilisation".

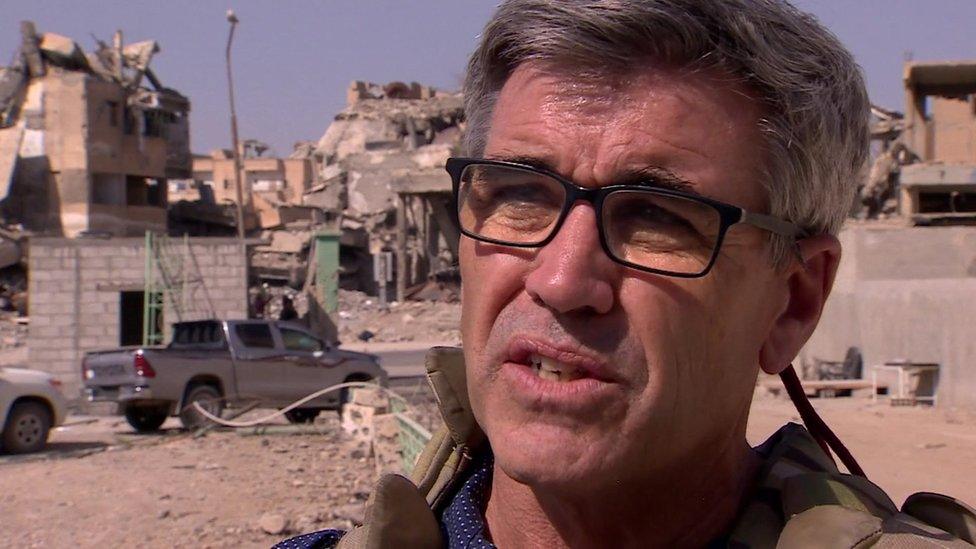

Patrick Connell, a senior US State Department official on the ground, says that means denying the extremists the "fertile ground they can recruit from". There are still IS sleeper cells operating in the city.

The US says it's already spent more than $8bn (£6bn) on humanitarian assistance right across Syria. Britain, the second-largest bilateral donor, has committed £2.7bn.

In Raqqa itself, some of that money has been spent on clearing some of the thousands of explosive devices left behind by the extremists, and providing food, medical supplies and education. But these efforts have stopped short of reconstruction.

Even that limited help is now in doubt. Raqqa's fear of being forgotten has been heightened by a decision by the Trump administration to cut more than $200m (£150m) earmarked for Syria's stabilisation.

US officials say it's being done to force other nations to do more. Patrick Connell says it's a signal from the president "that the burden needs to be shared". The US says a handful of other nations have already pledged contributions that will help ensure that work will continue.

But Raqqa still needs more support and it's the children of Raqqa whose futures will suffer without it.

The US State Department's Patrick Connell says the wider international community has an obligation to help out

Our US military minders took us to a school which is helping young children who've suffered the emotional and physical scars of the war.

The pupils included a girl who'd been forced to marry an IS fighter at the age of 11 and who'd then been divorced at 13 after she was injured.

Sitting in a classroom, two young boys who'd lost limbs were enthusiastically learning the alphabet. Both are among the victims of the thousands of explosive devices left behind by the extremists.

The State Department official overseeing the programme told us they were giving them the opportunity to learn and play that they were denied under IS. But the US funding for this programme will run out by the end of the year.

The US is keen to remind the rest of the world that, even if it's cutting its funding, it's not turning its back on north-east Syria.

There are still 2,000 US troops on the ground helping the Syrian Democratic Forces clear the last pocket of IS territory in the region. The US says they will stay until they ensure the "enduring defeat of IS".

The US funds projects like this school for children affected by the conflict but will no longer do so after the end of 2018

Maj Gen Pat Roberson, the US special operations commander on the ground, believes America is already "fulfilling its responsibility by ridding Syria of IS". He says the rest of the world now needs to help out, too.

The people of Raqqa are trying their best to rebuild the city. At the city's sports stadium, which was used by IS as a prison and execution centre, we witnessed signs of reconstruction.

Some of the work was being carried out by the same men who were brutally held in captivity by the extremists.

But on their own, they are just scratching the surface. It will take billions and billions of dollars to repair the damage of the war.

Ahead of the invasion of Iraq in 2003 the then US Secretary of State Colin Powell warned President George W Bush "you break it, you own it". But so far no-one seems willing to apply that rule to the reconstruction of Raqqa.