Can Iran survive sanctions?

- Published

New tough sanctions targeting Iran's oil sector, imposed by the United States, come into force on Monday.

The Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani, has responded robustly.

"There is no doubt that the United States will not achieve success with this new plot against Iran as they are retreating step by step."

Iran is heavily dependent on its exports of oil, and renewed sanctions, if effective, would hit the economy hard.

The EU has proposed supporting companies trading with Iran despite these new sanctions.

But will these companies risk being hit by secondary sanctions which would limit their own ability to trade with the US?

Why is America imposing sanctions?

Angered at what he describes as a terrible deal, President Donald Trump earlier this year pulled the US out of a multilateral agreement reached with Iran in 2015, under which strict controls were placed on Iran's nuclear programme in return for the lifting of a wide range of sanctions.

As a result, sanctions lifted by the US and others in 2016 are now being unilaterally re-imposed by the United States.

Iran has the fourth largest crude oil reserves in the world

But other countries, including those of the European Union, believe Iran is holding to its part of the bargain on the nuclear deal and have made clear their intention not to follow America's lead.

Such is the dominance of the US in global trade, that even the announcement of the renewed sanctions has been enough to trigger a wave of international companies pulling their investments out of Iran, and its crude oil exports have been falling.

How will US sanctions work?

The latest US measures exclude any company that trades with Iran from doing business in the United States.

In addition, under far-reaching secondary sanctions, any US company faces punishment if it does business with a company that does business with Iran.

Sanctions on the banking sector will also be introduced on Monday. In August measures were imposed on a number of industries including trade in gold, precious metals and the automotive sector.

The US has made it clear it wants eventually to cut off Iran's oil trade entirely, but has allowed eight countries to maintain imports as a temporary concession to give them time to reduce imports. US allies such as Italy, India, Japan and South Korea are among the eight, the Associated Press reports, external.

The IMF has predicted that Iran's economy will shrink by 1.5% this year

Getting around sanctions

In order to allow companies to trade with Iran and not face stiff US penalties, the EU plans to implement a payment mechanism - a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) - that will enable these companies to avoid the US financial system.

Like a bank, the SPV, would handle transactions between Iran and companies trading with it, avoiding direct payments into and out of Iran.

So when Iran exports oil to a country in the EU, the company from the receiving country would pay into the SPV.

Iran can then use the payment as credit to buy goods from other countries in the EU through the SPV.

The EU has also updated a statute - called a blocking statue - that allows EU firms to recover damages from US sanctions.

So will they hold?

Even with the EU plan in place, the costs of doing any Iran-related business could still be too high for many companies.

For example, even if the shipping operator were to purchase oil through the SPV mechanism, the company insuring the cargo may still face the threat of secondary sanctions and the potential loss of all its business in the United States.

Iran's economy isn't directly reliant on the US financial system, says Richard Nephew, a sanctions expert and senior researcher at Columbia University.

"But the issue is that most of Iran's biggest trading partners do and that affects their readiness to put at risk their access to the United States to do business with Iran."

He says small or medium-sized companies are more likely than large companies to use the SPV.

Another problem is that the product used in the SPV to trade with Iran may also violate secondary sanctions, says Leigh Hansson, head of international trade and national security at Reed Smith. "The transaction itself will be problematic."

Temporary compromise?

The US had insisted on cutting exports to zero but that seems unlikely as it would increase the price of oil, says Scott Lucas, a professor of international politics at Birmingham University.

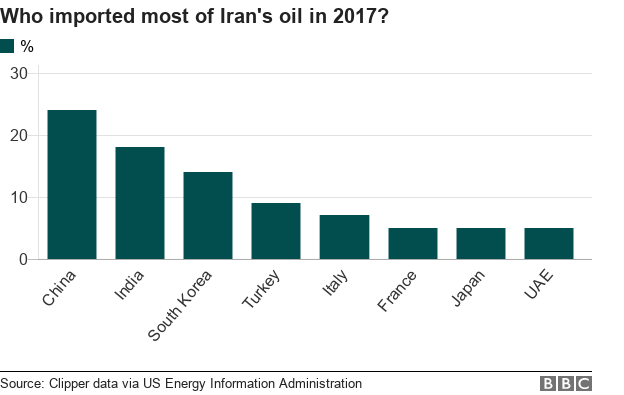

In addition to the countries allowed to continue buying Iranian oil, the backing of China, Iran's largest trading partner, may also prove critical.

The last time international sanctions were imposed on its oil industry between 2010 and 2016, Iran's exports fell by almost a half.

There's no doubt exports will be affected this time around too, but it's also clear that Iran and its remaining business partners will be working hard to maintain trading links.

"Don't be disillusioned about how painful this will be," says Ellie Geranmayeh, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. But "Iran has weathered multiple rounds of sanctions before."

Iranians will be forced into finding creative ways to sell oil, relying on their years of experience of life under previous sanctions.

And to fill the gap left by lost European investment, Iran will be looking east to forge new links with Russia and China.