Trump re-imposes Iran sanctions: Now what?

- Published

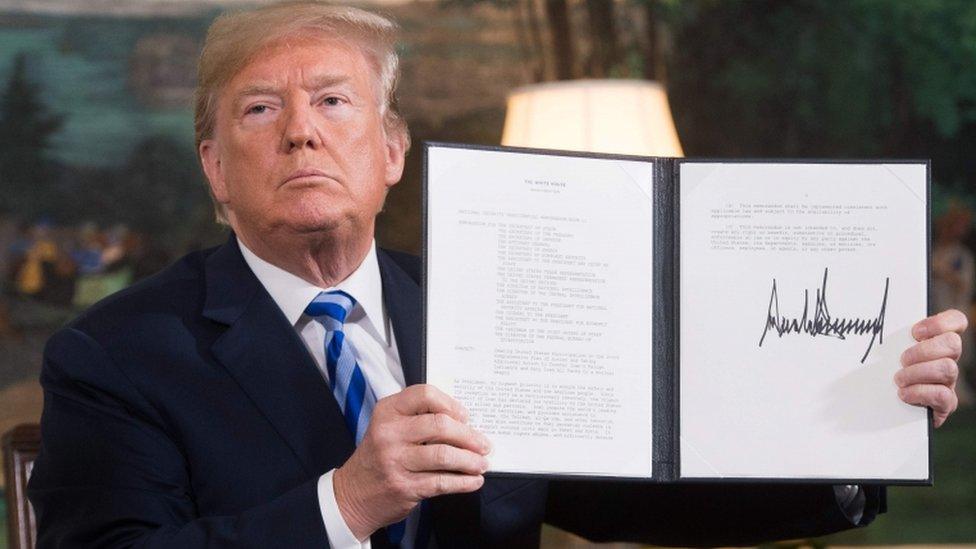

Donald Trump has signed a document that reinstates sanctions against Iran

The re-imposition of the full panoply of sanctions against Iran that were waived under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear agreement marks a high-point for President Donald Trump's foreign policy.

He had long objected to the agreement, which was seen by most analysts as one of the more significant foreign policy achievements of his predecessor Barack Obama.

Now the Trump administration's goal is to apply maximum pressure against the Iranian regime to compel it to think again and change what the Americans see as its malign behaviour in the region.

So what measures exactly are being re-imposed and what will their likely impact be? Will this mark the final demise of the JCPOA? And what is the real US strategy behind the sanctions effort? Not all of these questions have clear or definitive answers.

The sanctions that are being re-imposed are the most damaging to the Iranian economy - targeting its oil sales, its wider energy industry, shipping, banking, insurance and so on. In large part these are what is known in the trade as "secondary sanctions", in that they are intended to apply pressure on other countries to prevent them trading with Tehran.

The idea is to dissuade them from purchasing Iranian oil, which brings in a huge proportion of Iran's revenue. In addition, sanctions will be imposed upon hundreds of named entities and individuals.

UN inspectors say Iran, under Hassan Rouhani, has abided by the 2015 agreement

There will not be a sudden collapse in Iranian revenues. Indeed much of the damage has already been done.

The pressure has been building since President Trump's original announcement last May. US officials assert that since then, Iran's daily oil exports have dropped significantly - by more than one third.

Foreign companies have had to decide in effect what is more important to them: business with Iran or business with the United States. Many major players have already announced the termination of projects in Iran.

Knowing the sanctions were coming, many business have already made their decisions.

Several of Iran's customers may continue to purchase oil and look set to be granted waivers by the United States to do so. In the past - under the Obama administration - these were known as "significant reduction exemptions" and meant, in effect, that if countries promised to reduce their oil purchases from Iran significantly, then the administration did not seek to punish them for conducting some trade.

This made good sense as it helped US allies like Taiwan, South Korea and Japan manage their energy problems while falling into line with the broad thrust of US policy. India also got exemptions, and China reduced its purchases under a slightly different arrangement.

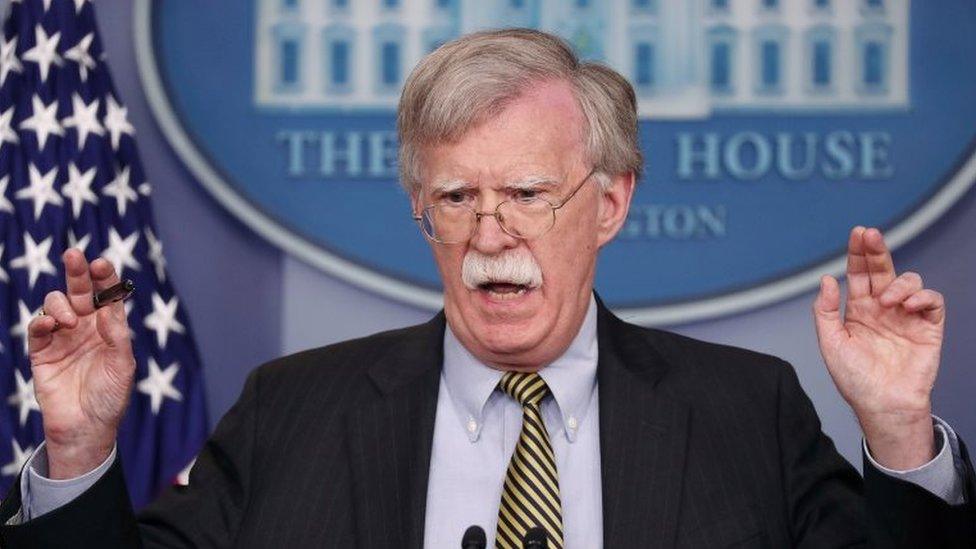

The Trump administration has already signalled that it too is willing to grant countries like India and several others such waivers. National Security Adviser John Bolton noted this week that: "We want to achieve maximum pressure (on Iran), but we don't want to harm friends and allies either."

Previously, the Trump administration had insisted that oil imports from Iran had to be reduced to zero.

Mr Trump (photographed at 2015 event) has been a vocal opponent to the JCPOA since its signing

China's behaviour - Beijing is a major trading partner for Tehran - is going to be key. It too is likely to continue buying Iranian oil without facing sanctions.

There is a logic here. Is the US really going to hit Beijing with damaging secondary sanctions which would effectively mean risking an economic war, given the difficult state of the wider trade relationship between the two countries? Probably not.

Uncertainty ahead?

The US must also be concerned about the broader stability of the international oil market, not least given the political uncertainties in Saudi Arabia. Indeed, it is the Saudis who may be expected to pump more oil to make up for cut-backs in Iranian crude.

A further uncertainty comes from the European Union's efforts to bolster the Iran nuclear agreement by seeking to protect its own companies from US sanctions. There is also talk about establishing an alternative payments system that would not involve either the dollar or US banks. But experts in Washington - even those critical of the Trump administration's approach - remain highly sceptical that EU efforts, in the short-term, will make much economic difference.

National Security Adviser John Bolton has been particularly strong in his rhetoric toward Iran

The general view is that the EU's pronouncements have largely been intended to send a powerful political signal to Tehran of their opposition to President Trump's approach. That is not to say that they would not like to see constraints on Iran's missile programmes or a change in Tehran's regional behaviour. But they believe that the JCPOA (remember France, Germany, the UK and the EU are all signatories) remains a useful constraint on Iran's nuclear activities and should not be overthrown lightly.

So is the JCPOA now doomed? Not necessarily. Some experts believe that if China and other customers like India continue to buy a reasonable level of Iranian oil and if the EU maintains its political support for the deal, then Iran may possibly stick with it for the time being. However, once sanctions begin to bite - perhaps causing further economic unrest - then the fate of the JCPOA will depend upon the complex political battles between moderates and hardliners in Tehran.

All this begs the question: what really is the Trump administration's goal in all of this? Ostensibly it is to bring Iran back to the negotiating table to get a better and more comprehensive deal.

But many analysts feel that such a move from Tehran is highly unlikely and the scope of US demands suggests that the Trump administration's real goal is somehow to produce regime change in Tehran.

Mohammad Javad Zarif praises European efforts to preserve the nuclear deal

As one expert critic of the Trump policy told me: "At the end of the day, the problem is the administration has no real plan. They know how to make use of one tool, i.e. sanctions, but they lack any semblance of a broader strategy." Jarrett Blanc, a former Obama era official who handled the implementation of the JCPOA, argues that by reneging on the deal, "the US has blown its ability to make credible promises".

So for the immediate future there will be a messy situation where Iran tries to weather the sanctions pressure: its oil sales will be reduced significantly but it will still retain some of its customers. The US will persevere with its current approach seeking to isolate Tehran - but without the broad international backing that the sanctions regime garnered prior to the negotiation of the JCPOA.

Few analysts believe that Iran's foreign policy in the region will change much. They say it is based on strategic and ideological concerns, rather than simply economic ones, and in any case its activities in Lebanon, Syria and Gaza are probably not expensive enough to trump these other priorities.

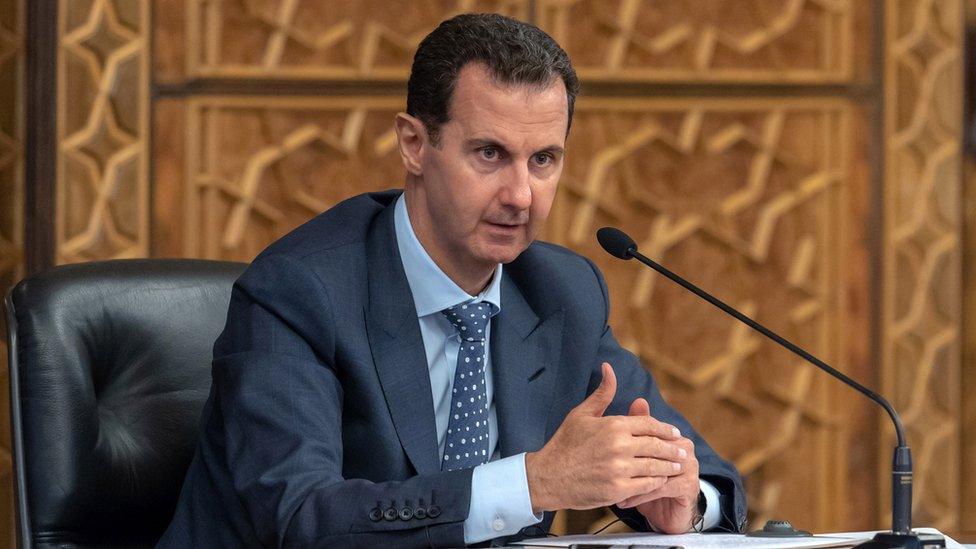

Iran is a major backer of Syria and its leader, President Bashar al-Assad

Nonetheless the Trump administration is clearly determined to up the pressure on Tehran. It especially wants to choke off funding for the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps responsible for conducting many of Iran's operations abroad.

This is part of a broader policy of containment if you like, in which Israel (through its actions in Syria) and Saudi Arabia (through its campaign in Yemen) are also involved. But Israel is already running up against problems with Russia, and there is a huge question mark over the future of the Saudi war in Yemen.

So much remains uncertain about the Trump approach. Can he win over allies, might he actually apply sanctions to those countries trading with Iran, and how long will the waivers on oil purchases actually last? Just what will be the impact upon Iranian society and its politics? And amidst this maelstrom can the JCPOA survive in any meaningful form?

But there is also a wider long-term question here about US policy which relates to Washington's growing recourse to the tool of economic sanctions. Many believe that they are being over-used and that the threat of secondary sanctions is counter-productive to other US goals.

It is not just the Europeans: Russia and China are also talking about developing alternative international payment systems.

We could look back - perhaps a decade from now - and say that this was the moment when the utility of US economic sanctions as a diplomatic weapon began to erode.

- Published3 October 2018

- Published23 November 2021