What is Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt doing in Iran?

- Published

Jeremy Hunt's visit to Tehran comes amid tensions between the two countries over UK dual nationals detained in Iran, and the war in Yemen.

There is an old joke in diplomatic circles that Iran is the only country in the world that still thinks the United Kingdom is a great power.

Instead of viewing the UK as a middling-sized European country, senior Iranian figures have seen a post-imperial nation still bent on meddling in the Middle East, exerting its exaggerated influence across the region.

This is in part a reflection of Iran's lingering resentment of Britain's role in helping to depose an elected prime minister here in the 1950s. It also reflects the UK's close relationship with the United States, a country with which Iran seems to be in a permanent state of confrontation.

So when Jeremy Hunt arrived in Tehran this week for his first visit as foreign secretary, he was not ignored. He had a long meeting and lunch with his counterpart, the veteran foreign minister Javad Zarif.

He was also granted a rare meeting with the Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, Ali Shamkhani, a powerful figure in Iran's military. Iranian media packed in to film him, and his visit made the local papers. (I am sorry to report that this does not happen everywhere a British foreign secretary goes these days.)

This attention on Mr Hunt, though, was not just because of Iran's historic perspective of the UK. It was also because right now Iran needs the UK's help.

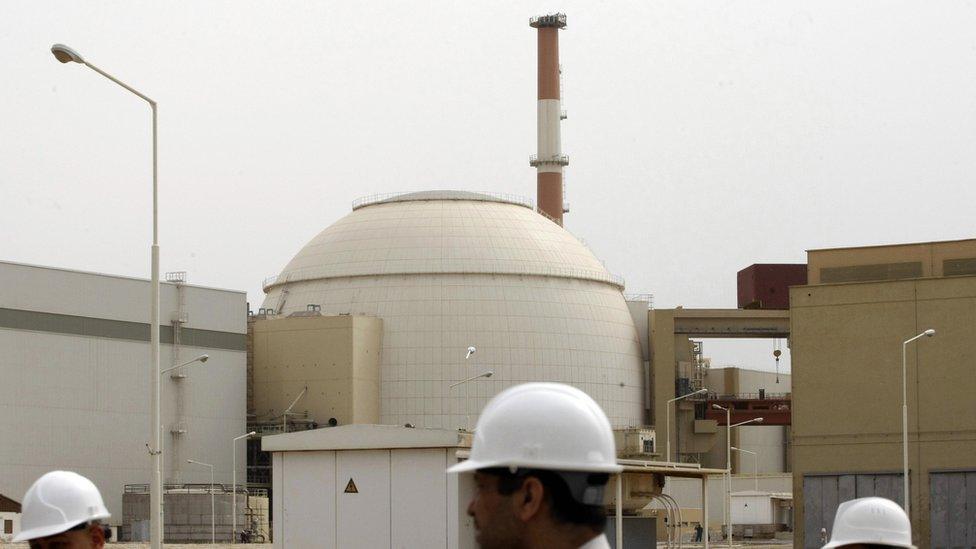

Since the United States withdrew from the deal to curb Iran's nuclear ambitions and re-imposed sanctions, Iran has been desperate to protect its trade with Europe.

The US has re-imposed sanctions on Iran over its nuclear programme

Britain and the EU have promised to help but are struggling to find ways of encouraging European firms to continue doing business with Iran. Many firms are pulling out for fear of US fines and loss of trade.

There is a plan for the EU to set up a special financial system that would allow Iran to barter its oil exports in a way that could avoid US sanctions. But nothing is happening quickly, and many doubt it will work.

Foreign Minister Zarif told me: "We need to see some action. We welcome the political commitment from the UK and (other European countries) but we believe that political commitment needs to be followed by action."

The Iranians can be phlegmatic about the impact of US sanctions. Officials here frequently refer back to the way Iran coped with its eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s, when more than half a million Iranians died.

Analysts speak of Iran's "resilience economy". But even Mr Zarif admits to me that these new sanctions will hurt: "Ordinary people will suffer, our economy is going to suffer."

So this was the context of Mr Hunt's visit and it was a fair diplomatic wind he appeared determined to use to deliver some key messages. Much of his focus, inevitably, was the fate of British-Iranian nationals such as Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who have been detained by the regime.

The foreign secretary was outspoken in threatening consequences for Iran if they were not released. But Mr Zarif said he was not in a position to discuss the legality of such cases, because they were the result of decisions made by Iran's judiciary.

Mr Hunt tried to see a senior judge yesterday, but after much coming and going, the meeting failed to materialise.

I asked Mr Zarif why Iran could not release Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe - not only to correct a gross injustice, but also to improve relations between the UK and Iran.

The answer that he could not give me is that there are some Iranian hardliners who want nothing of the sort and are using the detained British dual nationals deliberately to sour diplomatic relations. And until that changes, Mrs Zaghari-Ratcliffe's fate remains bleak.

British national Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe has been detained in Iran since April 2016

The real diplomatic focus of Mr Hunt's trip was his push for an end to the fighting in Yemen. Iran plays a key role here as the international backer of the Houthi rebels, providing them with money and missiles, according to the US, something Iran denies.

The foreign secretary urged Iran to encourage the Houthis to come to the UN-backed talks in Stockholm later this month to see if a cessation of hostilities can be agreed and a political process begun.

Mr Hunt is cautious, telling me that "both sides don't trust each other further than they can throw each other." But he was also optimistic that confidence-building measures could gradually bring the Saudis and the Houthis to the table. Britain is in charge of the negotiations at the UN in New York, and is circulating a new resolution to this end.

The problem here in Tehran is that the Iranians do not think the Saudi-led coalition, which is fighting the Houtis, is going far enough. The Saudis have agreed to stop targeting civilian areas in Yemen.

But Foreign Minister Zarif told me that this had too many loopholes, and Saudi Arabia should stop all its military operations. Otherwise it could carry on launching air strikes and just claim it was not targeting civilian areas.

Iran is a backer of the Houthi rebels in Yemen's civil war

The fact that Mr Hunt pressed ahead with this trip despite the political turmoil in Britain - and at the risk of angering US allies - reflects the importance he places in improving Britain's relations with Iran and landing some key messages, particularly on Yemen.

He told me that Iran is one of the great historic civilisations in the world that, like Russia, is desperate for international respect but is going about it in the wrong way. He said it had to end what he regarded as disruptive behaviour in the region.

The problem is that analysis is not shared by everyone in Tehran and Washington. The hardliners here project their country's power through military force and proxy political support in places like Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen.

And hardliners in the Trump administration see Iran as the world's greatest sponsor of terrorism, a country bent on securing nuclear weapons. And for now, some modest diplomacy from a middling-sized European power is not going to change that hard reality.

- Published4 November 2018

- Published14 October 2024