Syria war: Last puppeteer of Damascus is given lifeline

- Published

Syria has a long and rich history of shadow puppetry but modern technology and seven years of war has seen the art form suffer from serious decline, the UN's cultural body has warned.

Last week, the ancient form of storytelling was added to Unesco's list of cultural activities, external in urgent need of saving.

And no-one was more pleased by the move than Shadi al-Hallaq, the only shadow puppeteer left in Damascus. He hopes that international recognition from the UN will revive the art.

"When they rang to congratulate me, it was like a day dream," the 43-year-old puppeteer told AFP news agency.

"There's no-one in Syria who masters the art except me."

Shadow puppetry, also known as shadow play, grew in popularity across the Middle East, particularly Turkey, Egypt and Syria, during the Ottoman era.

For centuries, puppet theatre has also captivated audiences across parts of south-east Asia, China and India.

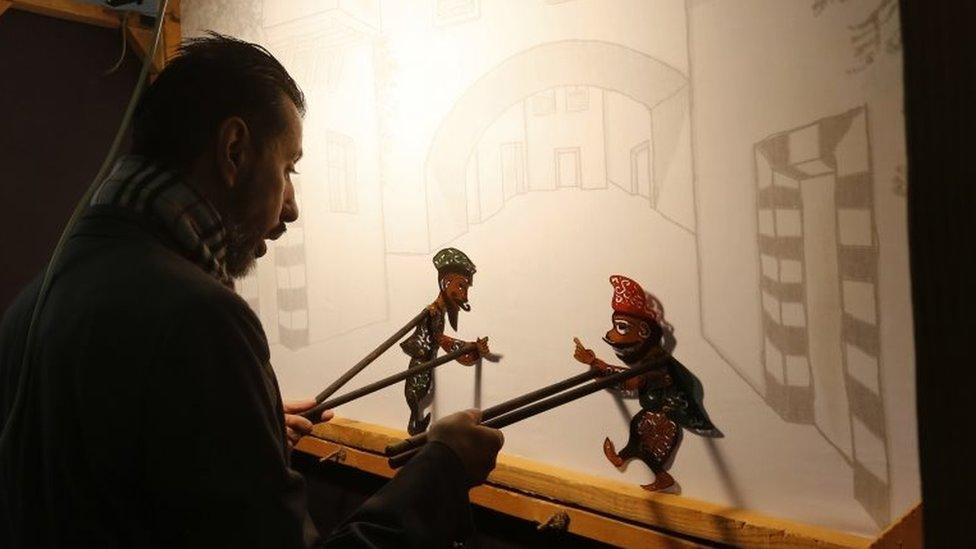

Traditionally storytellers used puppets made from stretched animal skin in front of a translucent screen to entertain their audiences in coffee shops.

Shadi fled Syria after the conflict erupted in 2011 and crossed into Lebanon where he worked for several years as a construction worker.

His mobile theatre set, as well as 23 hand-made characters, were lost to violence that flared up in eastern Ghouta, just outside the Syrian capital of Damascus, Reuters reports.

Shadi works with two traditional characters, the naive Karakoz and his clever pal Aywaz, to tell the story of unscrupulous traders based in the old city of Damascus.

He controls the puppets on sticks pressed against the screen with a light behind so that their shadows are projected for the audience to see.

According to Unesco, shadow plays offer humorous social criticism through satirical narratives involving the two main characters. But many of the shows would also feature female characters and talking animals.

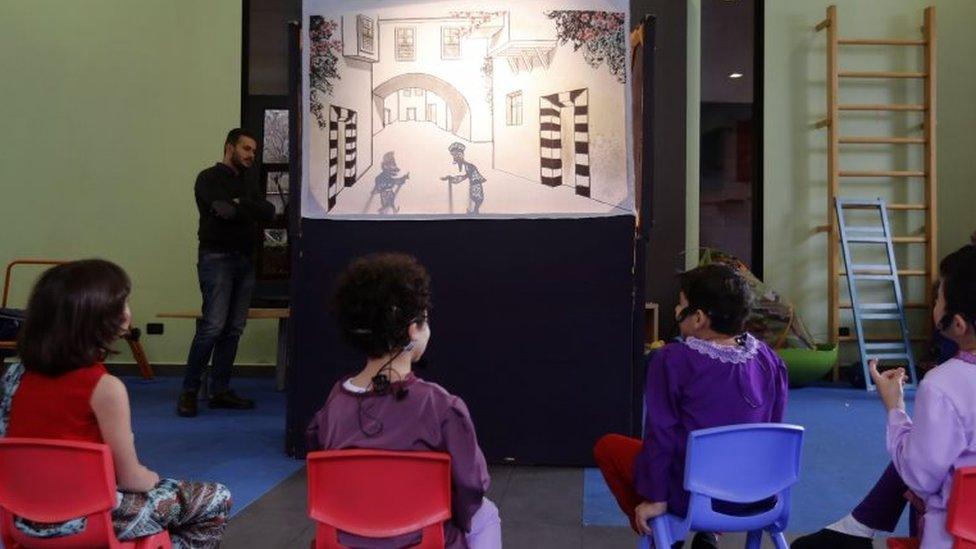

Unesco officials first noticed Shadi performing his art for Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. Now, he is back in Damascus, and performing for groups of children and adults.

"My audience are old and young - from three years old to old men in coffee shops," he told AFP.

Even before the war in Syria, the art was in decline with only a handful of performers across the country.

Shadi will soon begin teaching a group of Syrians who want to become puppeteers, a Syrian cultural official told Reuters.

"I can imagine how happy people will be to see this art survive and not disappear because it is part of our heritage and our culture," he said.

.

- Published28 October 2018

- Published25 February 2017

- Published13 October 2016

- Published6 August 2014

- Published6 March 2014

- Published27 November 2013