The enduring appeal of violent jihad

- Published

The Islamic State group (IS) has lost its short-lived caliphate in the Middle East, with hundreds - possibly thousands - of would-be international jihadists stuck in limbo, and tempted to return home despite fears of arrest and imprisonment.

Yet the scourge of violent jihad - where extremists attack those they perceive to be enemies of Islam - has not gone away.

The hotel attack in Nairobi two weeks ago by the al-Qaeda-affiliated militant group al-Shabab was an uncomfortable reminder. Large swathes of north-west Africa are now vulnerable to attack by marauding jihadists. Somalia, Yemen and Afghanistan remain ideal refuges for jihadists.

So just what is the enduring appeal of violent jihad for certain people around the world?

Peer pressure

The decision to leave behind a normal, law-abiding life, often abandoning family and loved ones to embark on what is frequently a short, dangerous career is a personal one. Jihadist recruiters will play on the notion of victimhood, sacrifice and rallying to a higher cause in the name of religion.

For nearly 20 years now the internet has been awash with gruesome propaganda videos, some portraying the collective suffering of Muslims in various parts of the world, others depicting revenge attacks and punishments inflicted on perceived enemies.

These serve two purposes. The first is intended to arouse sympathy and even shame, that the viewer should be watching comfortably at home on his or her laptop while "your brothers and sisters are being murdered" - in say, Syria, Chechnya or the Palestinian Territories.

Last September the BBC spoke to two British extremists who have lived and fought in Syria for years

Secondly, the revenge videos appeal particularly to those of a sadistic nature, often attracting those with a violent criminal record.

Peer pressure can be the trigger that tips an individual over from being simply angry about events in the world to taking violent action.

In Jordan I interviewed a convict in prison who had been persuaded by his best friend from school to come and join him in Syria with IS. He did, then regretted it, escaped back to Jordan and was then sentenced to five years in prison.

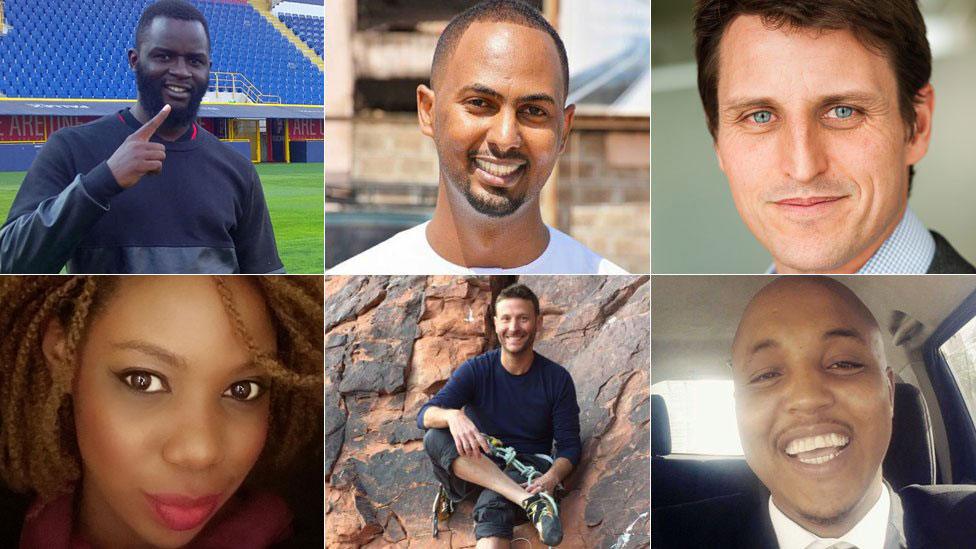

Those who are especially vulnerable to recruitment are young men and women who have grown apart from their families or their societies.

For them, belonging to a secret, illegal organisation that appears to value them can be an attractive alternative. Even if it ends with them being told to strap on a suicide vest and blow themselves up in a market place.

Bad or absent governance

There is a reason why the Middle East has long been a primary source of global jihadism. Corrupt, undemocratic and often oppressive regimes tend to drive peaceful political dissent underground.

In the early 21st Century Syria has been the most glaring example of this. After nearly eight years of civil war, with Syria's President Bashar al-Assad largely victorious against the rebels, the vast numbers of citizens who have disappeared into his jails provide a source of recruitment for extremist groups.

In Iraq, a country turned upside-down by the ill-fated US-led invasion of 2003, sectarian discrimination has played a major part in the rise of al-Qaida and then IS.

For eight years the oppression of the Sunni minority by the Shia-led government was so profound that IS (a Sunni militancy) was able to present itself as "the protector of Iraq's Sunnis" and easily take over much of the country. It is widely predicted that IS will look to exploit any future grievances.

Yemen, Afghanistan, Somalia and the Sahel (Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad and Mauritania) all contain large areas of ungoverned or conflict-riven space where jihadists have been able to recruit, train and plan attacks.

In Afghanistan billions of dollars in international aid have failed to deliver the level of governance needed to stem the Taliban-led insurgency. Corruption is endemic and the police are seen by many as untrustworthy.

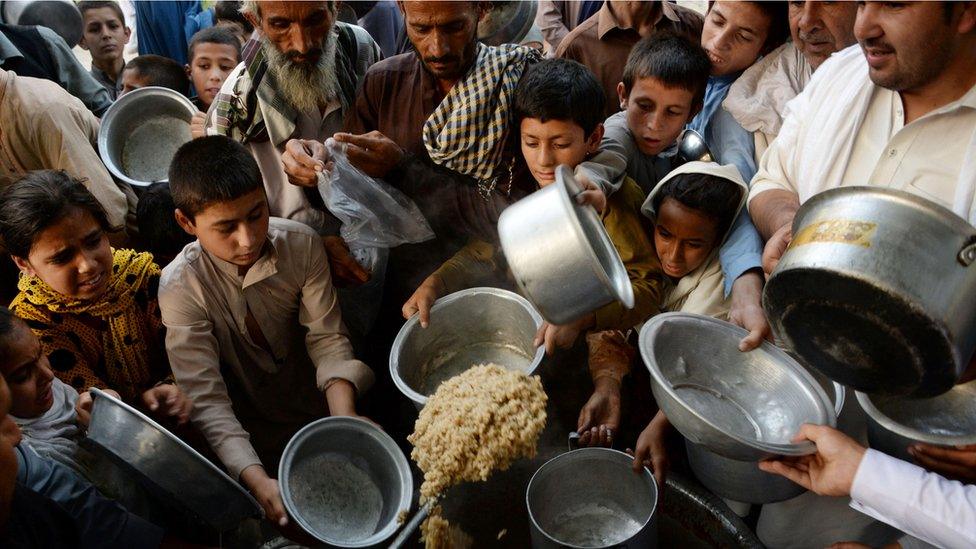

Some people turn to extremism in areas where basic governance, such as food availability, fail

The International Crisis Group (ICG) says state institutions there are so fragile, they are unable to "deliver basic services to the majority of the population". In remote, rural areas many Afghans prefer the draconian justice and rule meted out by the Taliban to that of the government.

Desperate poverty, lack of employment opportunities and poor or absent governance have all combined to make the Sahel countries bordering the Sahara fertile ground for jihadist groups. Many recruits join up, not out of ideology, but simply because they see it as the only alternative to destitution.

Religious duty

Recruiters for al-Qaida, IS, the Taliban and others have long been able to exploit religious obedience to draw young men and women into their ranks.

Extremism expert Dr Erin Saltman says extremist groups often promote "a narrative of struggle, heroic sacrifice and spiritual obligation in order to establish legitimacy and connect with potential recruits".

It is notable that after al-Shabab carried out its attack on the Nairobi hotel it gave as its justification the decision by President Trump to move the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, the third most sacred site in Islam after Mecca and Medina.

More than 20 people were killed in the Nairobi attack on 15 January

Jerusalem has been an emotional touchstone for many people in the Middle East and al-Shabab may be trying to broaden its appeal beyond Somalia.

The ideology behind violent jihad is likely to endure for some time yet, even though it is not shared by the vast majority of peaceful Muslims around the world.

Al-Qaeda has survived the death of Osama Bin Laden and still has its regional franchises in Asia and Africa. IS still has its followers, including in the UK, although since it is now deprived of a physical space to call its caliphate it may well struggle to attract recruits in such numbers.

On a global scale, containing and reducing violent jihad will require more than just good intelligence and police work. It will require far better and fairer governance, removing the drivers that spur people towards the violence that ruins so many lives.

- Published21 September 2018

- Published25 February 2018

- Published22 October 2018

- Published2 May 2023

- Published11 December 2014

- Published2 July 2015

- Published3 October 2014

- Published11 December 2014

- Published22 January 2019

- Published16 January 2019