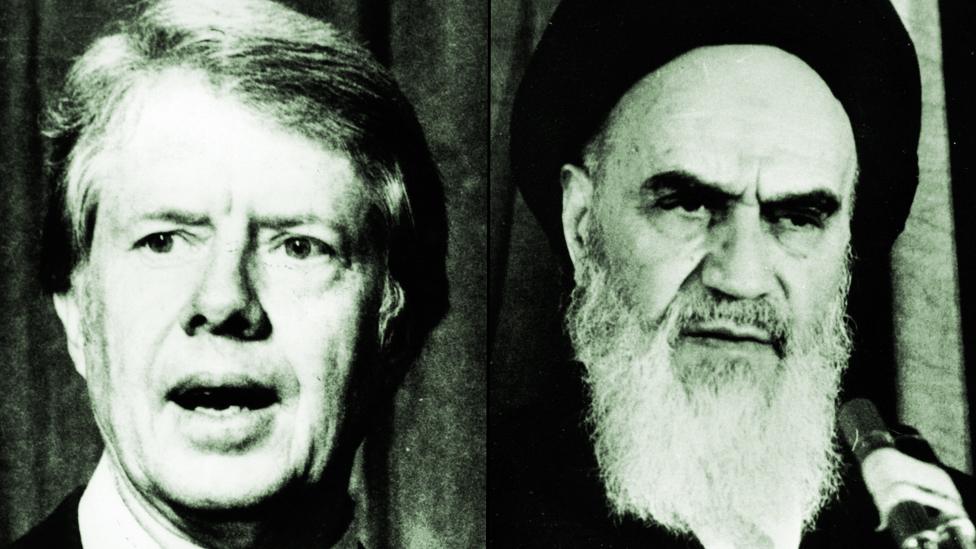

The plane journey that set Iran's revolution in motion

- Published

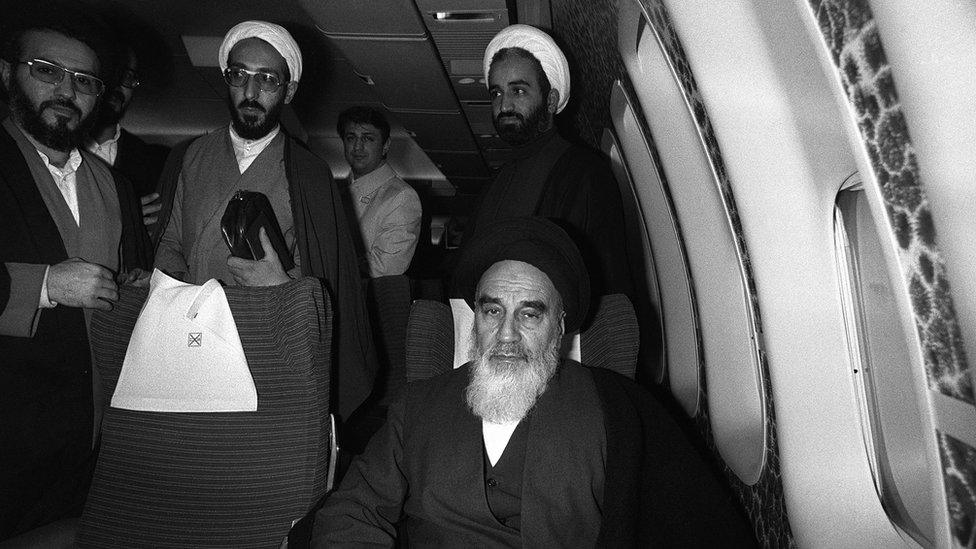

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned to Iran on 1 February 1979 after 15 years of exile

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini sat in the first-class compartment of the chartered Boeing 747, looking out through the window at the country he had had to leave 15 years before.

I stood over him, with my cameraman beside me, and asked how he felt now that his exile was over. No answer.

An American correspondent repeated the question. "Hichi," replied Khomeini. "Nothing".

The supporters of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who had been forced into exile a few days earlier, were scandalised by this lack of feeling.

But what he meant was that his return was not a matter for human emotions; the will of God was all that counted.

When I interviewed him the previous month at his place of exile outside Paris, Neauphle-le-Château, Khomeini had shown implacable determination.

"The monarchy will be eradicated," he assured me. "There are aspects of life under the present corrupt form of government in Iran which will have to be changed... Drugs such as alcoholic beverages will be prohibited."

"We are hostile to foreign governments which have forced the shah on Iran."

It is still like that, even today.

John Simpson was on board the plane that transported Khomeini from Paris to Tehran

At first, it had seemed impossible that the Islamic Republic could endure, but now it has lasted 40 years.

At election after election, Iranians turn out in their millions to vote for candidates who, though they have been carefully selected, represent the liberal and conservative tendencies in politics, and the liberal candidates usually get a majority.

But once they are in power, they find they cannot change anything.

Under Iran's constitution, the conservative forces - the clergy, the Revolutionary Guards, and so on - have a controlling interest, whoever wins the popular vote.

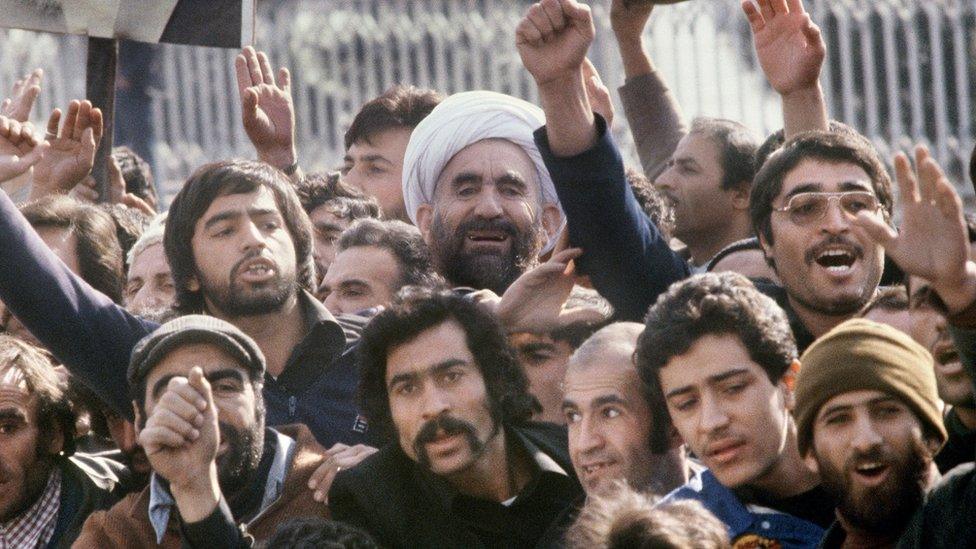

Khomeini was welcomed by a crowd of supporters at Tehran's airport

The supreme leader ranks above the elected president, and the conservatives are prepared to fight to keep their power.

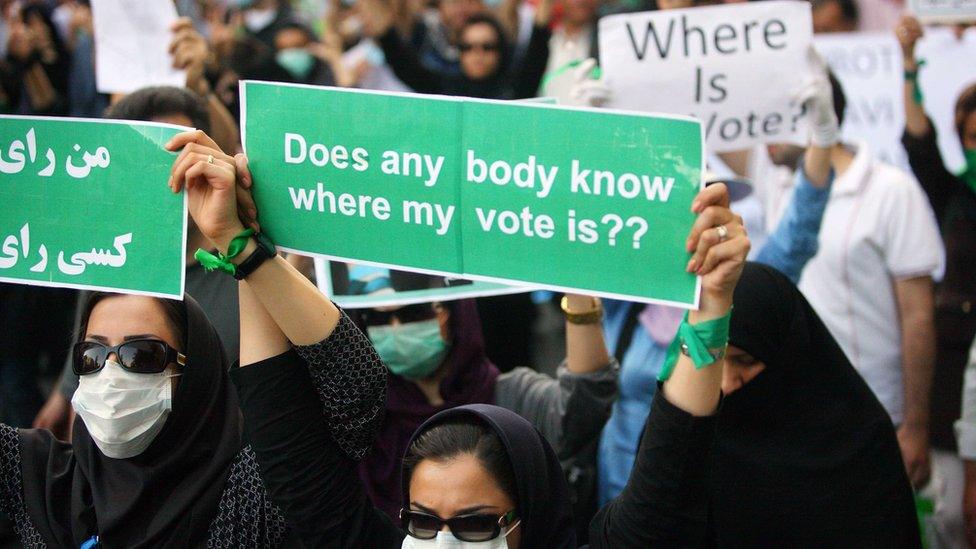

Immediately after the 2009 presidential vote, the conservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was declared the winner even though the liberal candidate, Mir Hossein Mousavi, had probably got a majority.

There were angry demonstrations for days on end, and it looked briefly as though a new revolution might be starting. But the conservatives hunted the demonstrators off the streets with great brutality.

The Islamic Revolution was back in power.

The disputed presidential election in 2009 triggered the biggest protests since the revolution

More than 90% of Iran's Muslims are Shia, and back in 1979 the ousting of the shah by Shia Islamist revolutionaries shocked and electrified the Islamic world.

Shia in countries like Lebanon and parts of the Gulf stopped accepting that they were at the bottom of the social and political pile, and demanded more say.

Sunnis in the region were deeply worried, yet they too were fascinated by the overthrow of a leader backed by the West.

The Americans were humiliated, and no-one in the Middle East would forget it.

Between 1980 and 1988 Iran was caught up in a savage war against Iraq, and it was obsessed with the need to survive.

But after 2003, when the US invaded Iraq and destroyed the power of the minority Sunnis there, Iraq's Shia majority began to dominate the country with the strong support of Iran.

Iran became a regional superpower - courtesy of President George W Bush. The irony could scarcely have been greater.

Nowadays, Israel and US President Donald Trump's administration see Iran as a major threat.

The UK and the European Union see things differently.

They accept that Iran is difficult and confrontational, but they think it is still willing to follow the lines of the agreement which former US President Barack Obama, with strong European support, reached with Iran over its nuclear ambitions.

Today, Iran appears a lot more easy-going than most outsiders imagine.

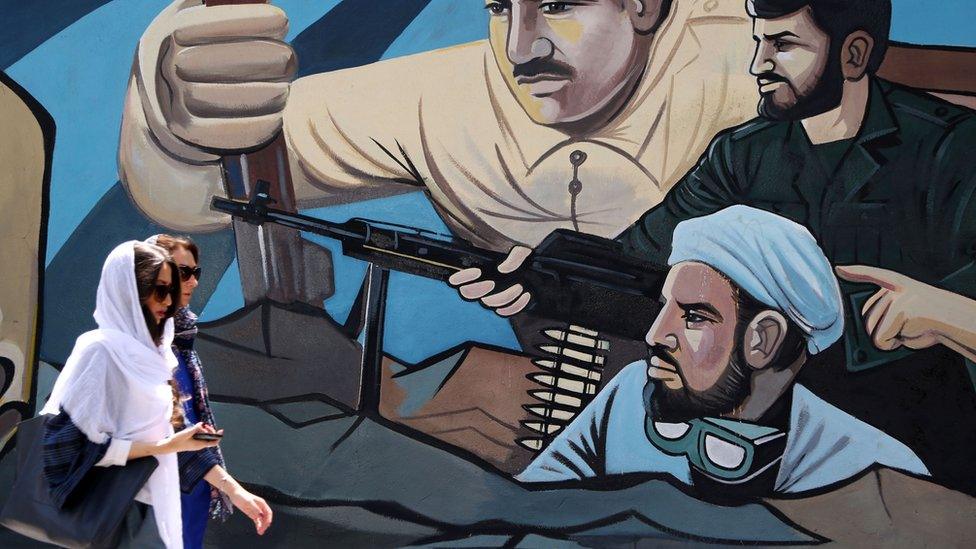

The rules about women's dress are sometimes enforced harshly, but the Islamic Republic has never clamped down on women's freedom of movement in the way you see routinely in Saudi Arabia with its male guardianship system.

In my experience, Iranian women have more belief that they can run businesses, own property, drive cars- and play an important part in politics, despite figures to the contrary, external.

Iran has imposed a compulsory dress code on women since the revolution

The present government is probably more liberal than any other since the revolution.

Ayatollah Khomeini probably would not have approved, but this approach has helped to protect the Islamic Republic over the years.

As far back as 1986, when I was first allowed back after the revolution, I worked out a formula to express what I felt about the new Iran: it was stable, but not permanent.

That still seems to be the case.

There is a lot of anger about corruption, but not as much as there was under the shah.

Iranian Revolution: Why what happened in Iran 40 years ago matters

Iran seems mostly relaxed, because there is no serious threat to the system. But it is hard to think that the strange balancing act between a weak liberal government, elected with mass support, and a tough and determined conservative core, can carry on forever.

The ferocity which Khomeini, vengeful and unsentimental, brought back from exile with him on his Boeing 747, has eased a lot. But it is still there.

And until there is some basic compromise between liberals and conservatives about the way the country should be run, Khomeini's revolution will always feel unfinished.

Clarification 17th June 2019: This article was amended to provide additional background information on the position of women in Saudi Arabia and Iran and to make clear that John Simpson is describing his experience of the two countries and the impact of the male guardianship system.

The Fall of the Shah

Listen to the BBC World Service podcast - a drama based on real events in Iran 40 years ago

- Published17 July 2015

- Published3 June 2016

- Published3 June 2015

- Published23 November 2021

- Published10 November 2017