Life inside the chaos left by the Islamic State group's fall

- Published

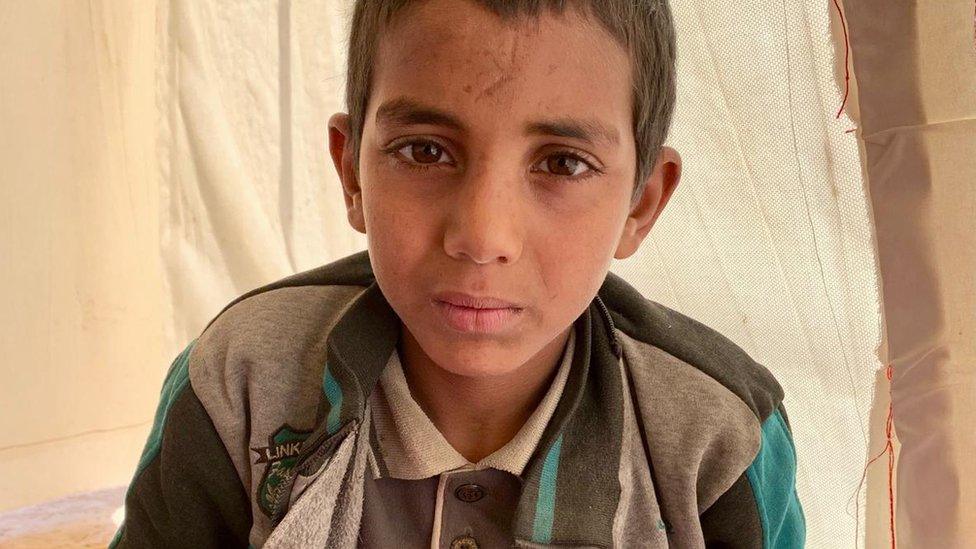

Children like Hamza are among the group's last evacuees

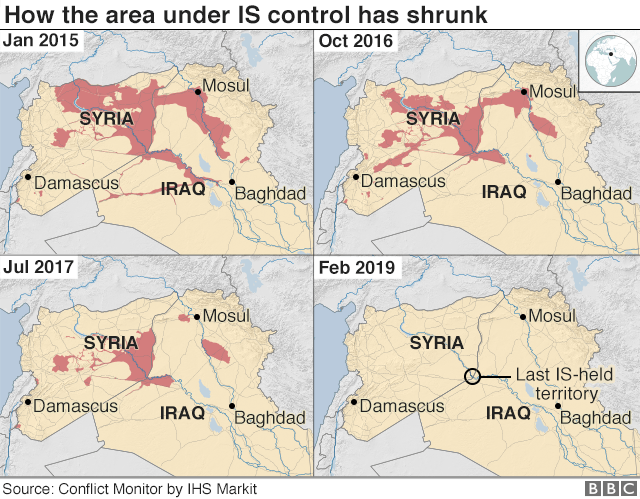

US President Donald Trump says "100%" of the Islamic State group's territory has now been taken over, even though local commanders with the US allies, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), maintain total victory will be declared within a week.

As the battle draws to a close, the BBC's Quentin Sommerville met some of those leaving the group's last stronghold, Baghuz.

Hamza Jasim al-Ali's world is small and terrible. He hasn't moved far in life, living always along the same 40km (25 mile) stretch on the banks of the Euphrates.

His journey, still without end, took him from al-Qaim in Iraq, across the border to Syria and into the dark centre of what was the Islamic State group's nightmare caliphate. He has seen more of life and death than any child of 12 should.

Now he is far from his river, sitting on the desert floor in a wind-whipped tent, alone - apart from an elderly woman who barely knows him. His leg is broken, but healing, and he smiles as I ask him questions.

I asked him what life was like inside.

"It was good," he says, smiling again. "Less food and water and a lot of fighting. It was heavy fighting."

Does he still like IS? "No. Why would I like them after all they have done?" he answers.

Hamza is an IS orphan. His father joined the group and took the whole family with him. He died five months ago, along with Hamza's mother and brothers and sisters in an air strike that was part of the battle to drive the group from its last toehold of territory in Syria.

IS's victims number millions - they displaced and terrorised people across Iraq, Syria and Libya. Their treatment of the Yazidis was genocidal, according to the United Nations. But they also brutalised and corrupted not just their enemies, but their own children, too.

Women and children are sent to displacement camps

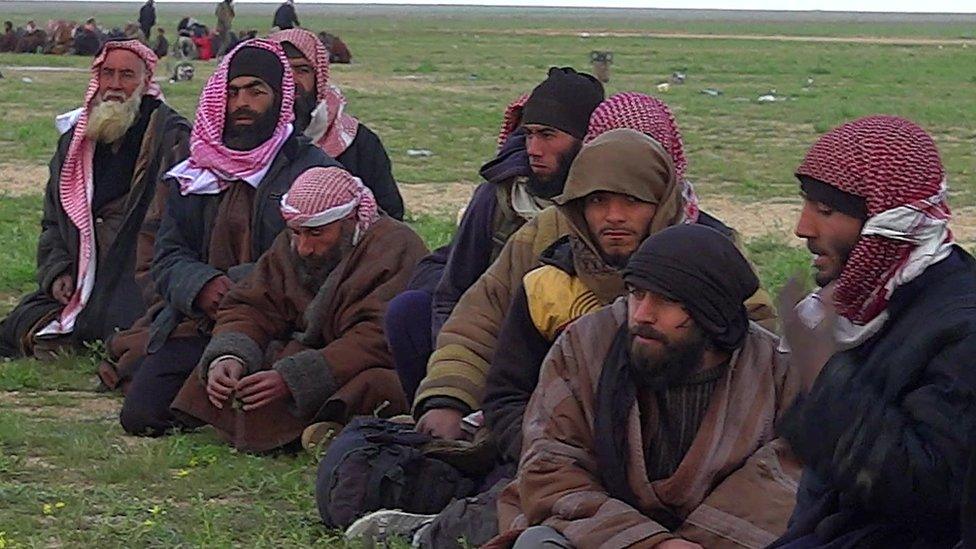

As part of a ceasefire deal, more than 6,000 women and children have left IS territory, along with injured male fighters. The Islamic State group's dreams of a sprawling caliphate have been reduced to a pathetic encampment around the village of Baghuz. Their first stop when they get out is the desert, where thousands are processed in the open. The air is acrid and filthy; many of them are sick. They defecate out in the open.

Most are then moved on to an overwhelmed internment camp near the city of Hassaka, in the village of al-Hol. As Hamza and I speak, there's a lull outside - the day's IS refugees have yet to arrive, and last night's have already been put on to cattle trucks for the long journey across desert roads to al-Hol.

Some have fled with suitcases containing the last of their belongings

Monitors say thousands have been evacuated in recent weeks

They are searched individually, by Kurdish women fighters, but it is not known if they are finger-printed or photographed. The injured men's pictures and other biometric data are taken before they are sent to detention. But there are limits to the investigations that can be carried out into the crimes of which they are suspected. It is not clear how long the Kurdish authorities can hold them. Some of the men said they expected to be freed in a few months' time.

One man, who said he was from Aleppo, claimed he was a caretaker. At the edge of the processing area, he told me: "I'll do the supposed detention time and then go live with my parents and leave everything behind me. I'll go live with my mum. That'll be best."

Another, Abu Bakr al-Ansari, showed little regret. "All Muslims will be sad it's gone because they wanted their own state," he says. "They won't live free to practise their religion in other Muslim countries."

Both were then taken away to Kurdish detention.

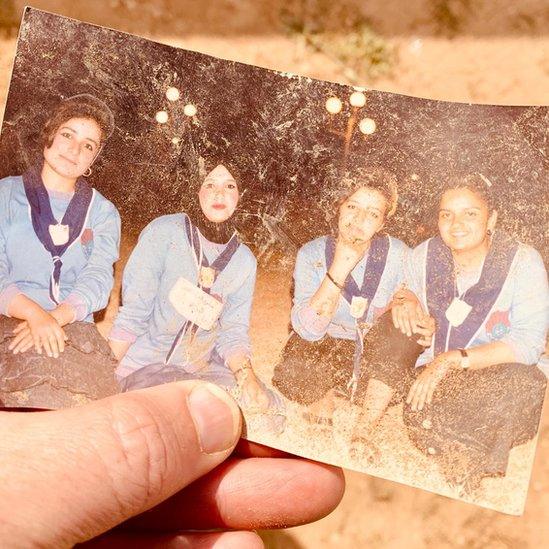

Across the desert plain, I find discarded belongings: mobile phones that have been smashed or burned in camp fires, USB drives snapped in two.

There are photographs in the dirt, too - one of four young girl scouts, another of a girl wearing a headscarf. Was one of them now on her way to al-Hol camp?

Personal belongings could be seen among scattered debris

Amid the soiled nappies and empty tinned cans of food, a family ration card. It belongs to a Kosovan family. The father had a senior position within IS. But that's another story.

In this mess of abandonment, there is purpose and care. A computer hard drive has been stamped on and covered in human excrement.

Many of the women left IS not because they wanted to, but because they were ordered to. Plenty still carried their husbands' worn military backpacks.

It appears that they want their enemies - the Kurds and the Western coalition - to have little clue to who they are. I met women from Turkey, Iraq, Chechnya, Russia and Dagestan. Some expected to be reunited with their husbands who are still inside Baghuz, waiting for the final battle. Many are still fanatics.

What to do with foreign fighters and their children has sparked fierce debate

Many of the women's husbands remained inside the Baghuz hideout

A Tunisian-Canadian woman, her niqab streaked with stains under purple-framed glasses, gave her name as Umm Yousef. Her husband, a Moroccan, had been killed, but she may have married another who was still inside. She said she had no regrets and had learned much from IS.

"So Allah, he made this to test us," she told me. "Without food, without money and without houses, but now I'm happy, because maybe some time, in two hours' I will see that I have water to drink."

Britain and other coalition countries are maintaining pressure on the Kurds to keep the dispossessed of IS locked up. But after the misery the extremists brought here, the Kurds want them gone.

At night more women arrived. Some of their children cried, but others stood silent and still, numb to everything around them. When they were asked a question, in the glare of television camera lights, they turned their dust-covered faces down to the ground and said nothing.

A group that showed almost no mercy, now pleads for it.

Exclusive pictures of final Islamic State group bastion

An Iraqi woman, standing in the dark, with around 200 other women and children, said to me: "Do you not see the children here before you? Can you not feel their pain? The pain of old men and the women who got shredded by the bombs? The children who died in air strikes? You're human. We're human as well. Do you not feel my pain, brother?"

At the edge of the throng, there is a medical station, run by a charity, the Free Burma Rangers. Paul Brady, a Californian, is one of their medics. He says the injuries have changed as more people have arrived from IS.

"About 10 days ago we saw quite a few with what looked like bullet wounds," he told me.

"They said they were shot because they were escaping. But now we haven't been seeing as many of those. It feels like most of these injuries are a little older, mostly from air strikes and mortars.

"You walk around this triage spot and it smells really bad because these wounds have been festering for a long time," he said.

The flow of people will eventually dry up, and then the final battle for Baghuz is expected. Those we spoke to in the desert said there were still thousands of fighters still inside.

One injured fighter told us he got out because "there's no Islamic State left"

Hamza was injured five weeks ago when he stepped on a landmine, but he says his broken leg is much better now. As I'm about to leave, he looks up at me, his smile finally disappearing from his face and he asks, "What will happen to me?"

There's no clear answer. And I couldn't tell him that Iraq may not take him back. He would probably be taken to al-Hol camp like everyone else.

I left him something to drink, some chocolate and bananas, in the care of the medics and the Kurdish forces.

When I returned to the desert the next day, he was gone, his place on the floor taken by more sick and injured from the last of the so-called caliphate.

- Published22 February 2019

- Published22 February 2019