Iran oil waivers: Is it about to become more expensive to fill my car?

- Published

Middle East tension might translate to prices in the forecourt... or maybe it won't

"The goal remains simple," US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said on Monday while announcing new measures against Iran.

That goal, he said, was "to deprive the outlaw regime of the funds it has used to destabilise the Middle East for four decades, and incentivise Iran to behave like a normal country".

The US, Mr Pompeo announced, would end exemptions from sanctions for countries that were still buying oil from Iran. Those countries include close US allies, who may now face sanctions if they keep buying Iranian oil.

This decision could have knock-on effects outside this corner of the Middle East (even in your pocket), and comes after months of growing tension between Iran and the US.

How hard will this hit Iran?

First of all, some context as to what led to this point.

Back in November, the US placed new sanctions on Iran, as President Trump withdrew from a deal agreed in 2015 that aimed to curb Iran's nuclear ambitions. The US has also condemned Iran's role in Syria and Yemen's wars.

When it announced these sanctions, the US placed waivers allowing eight countries or territories to continue importing oil from Iran, to give them more time to find a new seller.

Three of those buyers did so, but five did not: China and US allies India, Japan, South Korea and Turkey. From 2 May, those countries won't be covered by waivers any more, and could face US sanctions if they continue to import Iranian oil beyond that date.

The Financial Times reports that as well as the 1.3m barrels of oil that continue to be (officially) exported from Iran every day, more are being shipped out under the radar.

How is that possible? Alexander Booth, of data intelligence company Kpler, told the BBC that Iranian ships switched off their transponder trackers about 80% of the time. This means that it is difficult to track what the ships' cargo is, where it has come from and where it is going. Kpler's analysis suggests Iranian barrels are even moved between ships on the high seas.

Even with the large number of barrels being exported daily, Mr Pompeo said the US intended "to bring Iran's oil exports to zero" from 2 May.

This would require all those five countries to be on board and Turkey and China, for example, have made it clear they don't appreciate being told what they can and can't import.

Given that Turkey and China account for about half of all Iranian oil exports, it was not credible to expect all exports to come down to zero, Mr Booth said.

How much does Iran depend on oil?

Mr Pompeo said on Monday that lifting the waivers would deny "the regime its principal source of revenue".

He's right, in a way - oil is the biggest single source of revenue for Iran, but it doesn't make up the majority of its exports.

Iran's petroleum exports were worth $52.7bn last year, according to Opec, and its total exports brought in $110.8bn. It also makes money from exporting chemicals and metals, among other things.

Put starkly: imagine a scenario where a half a country's revenue suddenly dried up.

Even before the US waivers were confirmed this week, the International Monetary Fund had said it expected Iran's economy to contract by 6% this year.

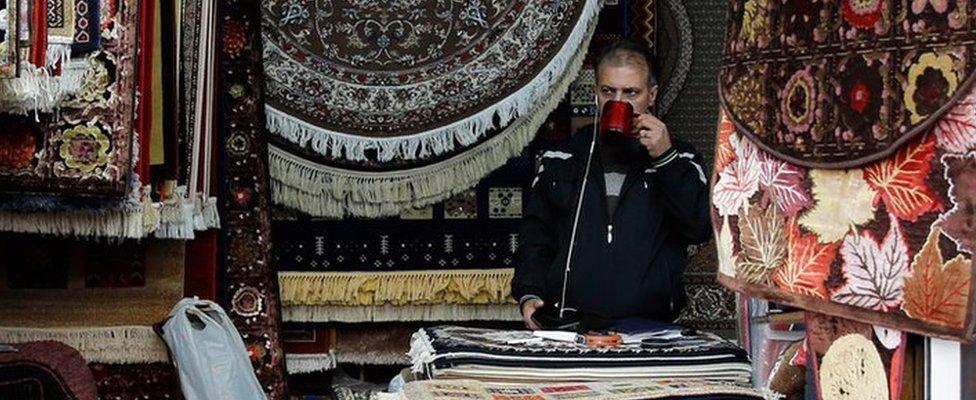

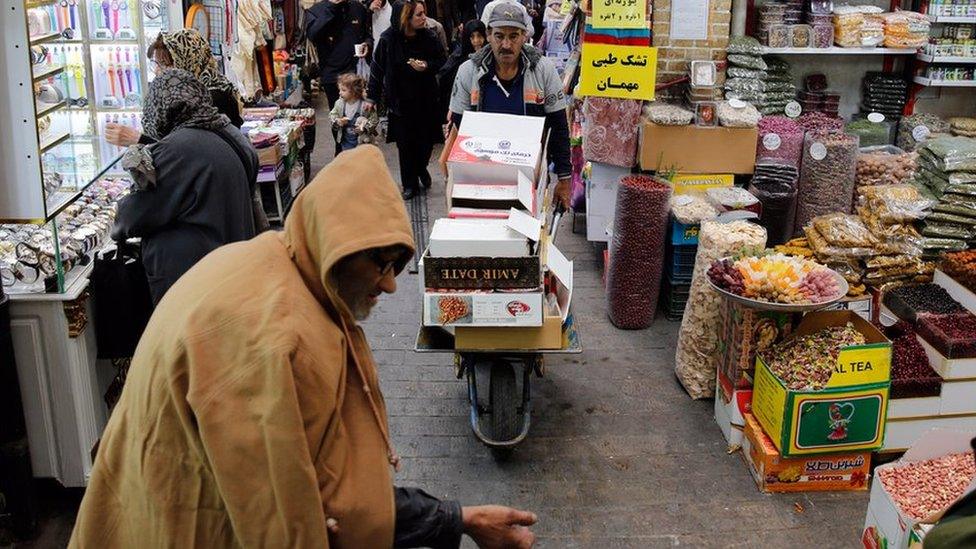

Iran's 81m people had already started to feel the pinch in recent months as its oil exports slowed down and other US sanctions hit its energy, ship-building, shipping, and banking sectors.

Inflation in Iran has been rising significantly. Households are having to spend 47.5% more per month compared with the same time last year, external and rural households in particular are being hard-hit by rising prices.

Back in November, we interviewed Iranians about how US sanctions were affecting them - you can read their stories here.

Will this change the price of oil?

There's one sure-fire consequence to the oil supply being threatened: the price of oil rises. And that's exactly what happened after the US waivers were lifted on Monday.

The price of Brent crude rose to $74.34 a barrel (£57.23), its highest point since 1 November.

3.33%increase in price of Brent crude oil after US announcement

The US has tried to reassure the market, and customers, that the world will not soon be facing a shortfall in oil supply.

Mr Pompeo said two close US allies - Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates - would step in and boost production to plug the gap.

But there are already disruptions in two other major oil-producing countries: Venezuela (which is under US sanctions) and Libya (where violence has broken out in recent weeks).

Alexander Booth, of data intelligence company Kpler, said Saudi Arabia and the UAE would be unlikely to be able to meet the demand by themselves. Russia would need to increase its production too, he said.

The risk, he added, is that the oil industry could find itself with little wiggle-room if supply was hit unexpectedly somewhere else - with violence in Nigeria, for example.

So does this mean you will soon have to start paying much more to fill your car?

As a UK consumer, it should not make too much of a difference because one of the biggest factors in the price you pay for petrol is fuel duty, not the price of a barrel.

However, Mr Booth said consumers in the US and elsewhere could be more vulnerable to changing prices over the coming months. The response from the White House, from where the president has already railed against high oil prices, could be worth watching.

How might Iran react?

Iran doesn't have much room for negotiation. But it does have one advantage: geography.

A huge amount of the world's oil has to travel through the narrow Strait of Hormuz, at the entrance of the Gulf near Iran. All that Saudi and UAE oil that will need to be produced to balance out the loss of the Iranian product will have to pass through the strait.

Iran has repeatedly threatened to block Hormuz, which is 33km (21 miles) wide at its narrowest point and has a shipping channel only two miles wide. An Iranian naval commander said this again on Monday, after the US waivers were rescinded.

But has Iran ever taken the step of shutting the strait completely? Well... no. And is it likely to? Again, no.

"It's doubtful that Iran's military would actually attempt to close the strait for two reasons," said Michael Connell, the director of the Iranian studies program at the Center for Naval Analysis in Virginia.

"One - Iran's economy also depends heavily on the flow of commerce through the strait, which presumably would be closed to Iranian shipping in such a scenario. And two - to do so would give the United States, its coalition allies, and its Gulf partners a casus belli and lead to war, which would undoubtedly end badly for Iran, although everyone involved would suffer consequences."

More feasible, Dr Connell said, is a live-fire exercise that would effectively close the strait.

Doing so "would still allow Tehran to ratchet up the pressure, so to speak, without necessarily leading to war", he said.

- Published8 April 2019

- Published5 November 2018

- Published22 April 2019

- Published5 November 2018

- Published3 January 2020