Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi: Why is it so difficult to track down IS leader?

- Published

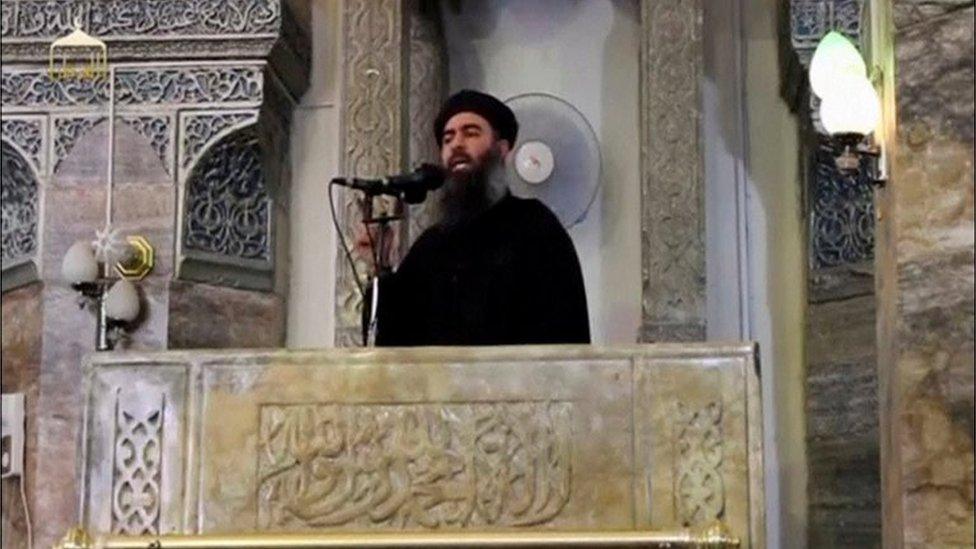

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has not been seen on video for five years

He is the world's most wanted man. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the fugitive leader of the Islamic State (IS) group and its self-styled "caliph", has a $25m (£19m) US government bounty on his head.

For more than three years he has been dodging capture, and ever mindful of his security, until now he has only ever appeared once in-vision, when he delivered his sermon from Mosul in 2014 declaring a "caliphate", ruled by him.

Earlier this week, Baghdadi resurfaced in an 18-minute online video, rallying his supporters but, not surprisingly, giving no clues as to his current whereabouts.

So where is he, how is he being searched for, and why cannot the US and its allies, with all their sophisticated technology, locate him?

Reports say that on 3 November 2016, Baghdadi made a mistake that nearly cost him his life.

The battle for Iraq's second city of Mosul was getting underway and US-led coalition forces were pressing in on IS fighters.

From somewhere just outside the city, Baghdadi made a 45-second radio call exhorting his followers to keep fighting. The message was intercepted by electronic eavesdropping aircraft operated by the coalition, a voice match was made and there was a frantic scramble to react.

But by then the IS leader was gone, moved on by his bodyguards and no doubt implored by them not to take to the airwaves in real time ever again.

It is unclear where the IS leader is

It took US intelligence almost 10 years to track down and kill Osama Bin Laden, between the day of the 9/11 attacks in 2001 until the small hours of 2 May 2011 when US Navy Seal commandos burst into his compound in Pakistan.

America's National Security Agency (NSA) and Britain's GCHQ have a staggeringly large capacity for Signals Intelligence, known as 'Sigint', monitoring, intercepting and decoding both open and encrypted communications around the world.

In the old days, terrorists on wanted lists would sometimes give away their locations by making calls from their mobile phones or staying online too long from one location.

Bin Laden was wise to that, and Baghdadi has been too - mostly.

The al-Qaeda leader was eventually tracked down to his Abbottabad lair not through his digital footprint but through the courier who ferried his propaganda videos and other messages by hand from there to wherever they were being uploaded onto the internet.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi's last appearance was in a mosque in Mosul in 2014

Tracing this reverse journey is likely to be one of the first things US intelligence is likely to be doing in the days following Baghdadi's video release, but his security team will be wise to that.

Only a very small number of trusted associates will be with him and they are likely to be moving him around constantly.

'Excellent operational security'

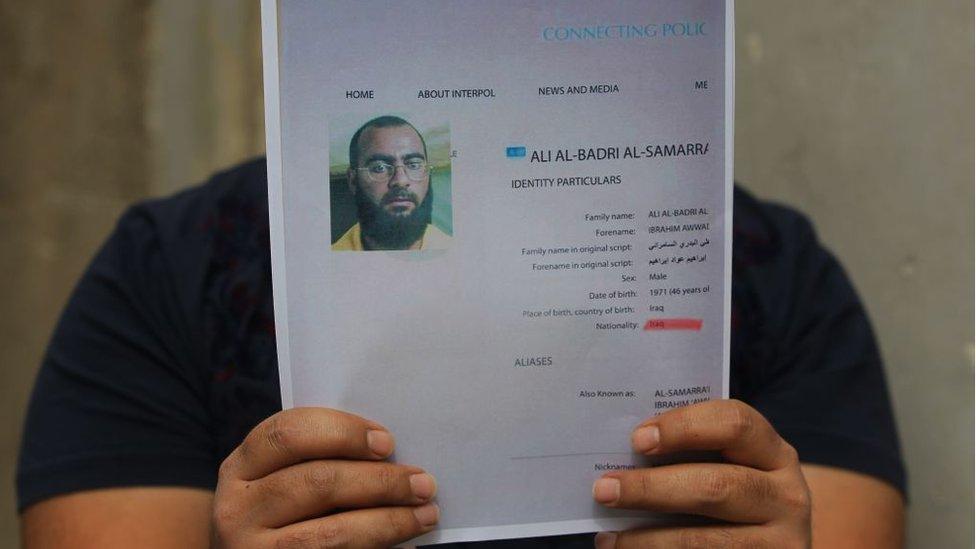

Born near Samarra, Iraq, in 1971, his real name is Ibrahim Awad al-Badri.

Deeply religious from an early age, he later spent time incarcerated in the US-run internment camp of Camp Bucca in 2004 following the Anglo-US invasion and occupation. There he forged close alliances with other inmates, including former Iraqi intelligence officials.

"He learned a lot on how to operate from Saddam's former intelligence officials," says Michael Stephens, a Middle East expert with the London-based think-tank Royal United Services Institute (Rusi).

"His operational security is excellent," he adds, "partly because of his excessive paranoia". Where is he hiding now? Almost certainly still in the Iraq-Syria border area, says Stephens.

"He'll be able to take advantage of established smuggling networks across that border," he says, "using money to pay his way amongst the tribes there".

Baghdadi forged alliances with former Iraqi intelligence officials during his time in a US-led prison

Iraq's former strongman Saddam Hussein went on the run for nine months after his regime was overthrown.

US operation Red Dawn tracked him down to an underground hiding place near his birthplace in Tikrit after a human informant betrayed his whereabouts for a multi-million dollar reward.

But getting such a "mole" inside Baghdadi's inner circle would be very difficult indeed. The tiny amount of people in close proximity to him could well be so loyal as to be beyond financial temptation.

So if the world's most wanted man is staying off-line, he is not making any calls on a mobile phone, and he is possibly moving around constantly from one hiding place to another, then what hope does Washington and the West have of ever finding him? (Preferably before he orchestrates or inspires the next major IS attack).

Ultimately, it may well come down to luck and patience: a chance sighting by an inquisitive villager, an unusual configuration of vehicles spotted by an alert drone operator, or even an exhausted and disillusioned IS member who decides it is finally time to take the reward money on offer and spend the rest of his or her life, fabulously rich and forever in hiding.

- Published27 March 2019

- Published23 March 2019

- Published23 March 2019

- Published8 March 2016