Franz Kafka papers lost in Europe but reunited in Jerusalem

- Published

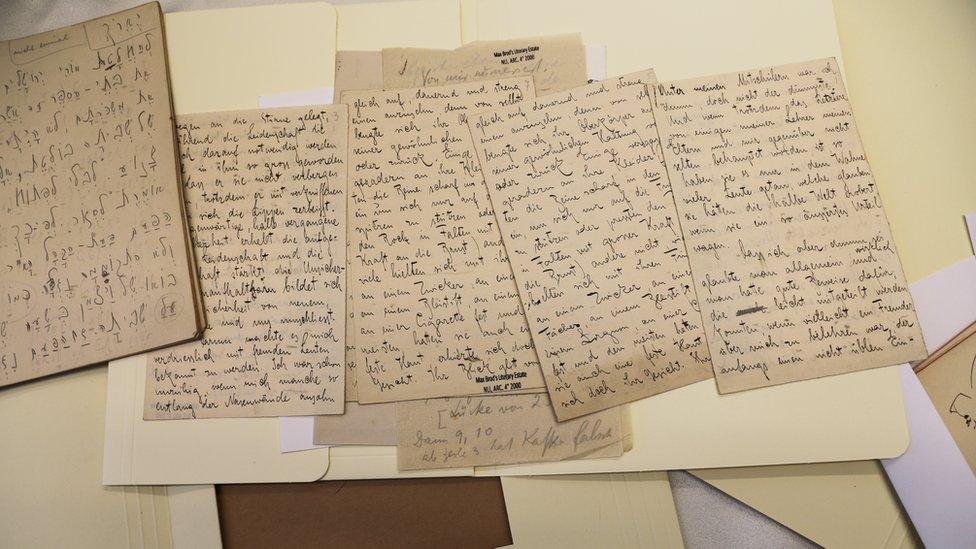

The papers have now been reunited after 11 years of searching

A "Kafkaesque" 11-year fight to bring together author Franz Kafka's papers has come to an end after the last batch arrived in Israel.

The National Library unveiled the documents after years of international searches and legal disputes.

It was left the collection in 1968 by Max Brod, the friend who Kafka had trusted to burn his writings after his death in the 1920s.

But Brod refused, later going on to publish them instead.

Brod then left the papers to the National Library of Israel in his will.

However, after he died in 1968 they disappeared - eventually sparking a hunt which led investigators to Germany, Switzerland, and bank vaults in Israel.

It was, the National Library's spokeswoman Vered Lion-Yerushalmi said, a story which was in itself "Kafkaesque".

The final batch, which has just been sent to Jerusalem, had spent decades stored in vaults at the headquarters in Zurich of Swiss bank UBS.

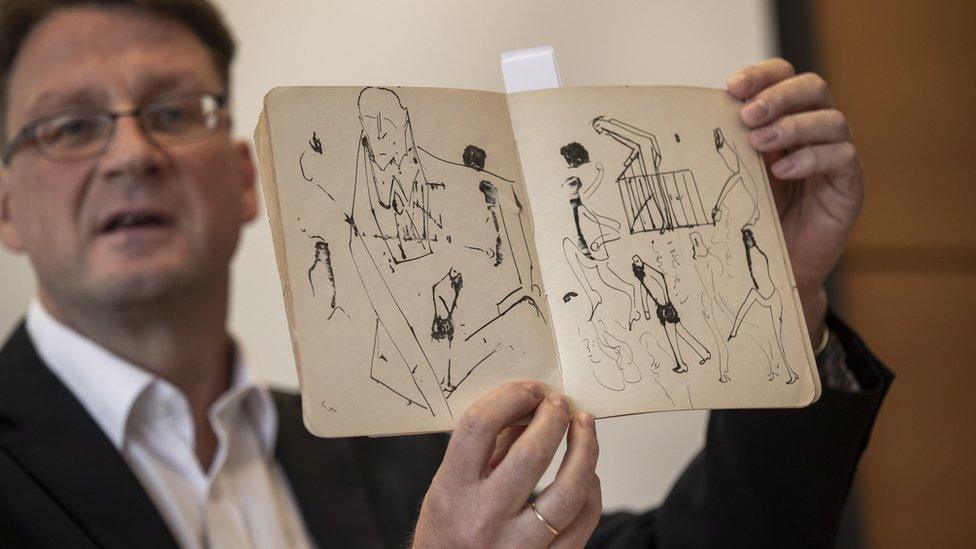

The latest cache includes some of Kafka's drawings

It includes a notebook in which Kafka practised Hebrew, three different drafts of his story Wedding Preparations in the Country, and hundreds of personal letters, drawings and journals.

The papers will now be published online, the library has said.

The masterpieces that could have been burned

Franz Kafka is recognised as one of the greatest writers of the 20th Century, and his works, including The Trial, Metamorphosis and The Castle, are considered literary masterpieces.

However, without his close friend Max Brod, Kafka would almost certainly have faded into oblivion.

Franz Kafka is considered one of the greatest literary figures in history

Kafka was suffering from tuberculosis in a sanatorium in Austria when he urged Brod to destroy all of his letters and writings. Brod refused and, after Kafka died in 1924, he kept the papers.

About 15 years later Brod, also a Czech Jewish writer, was forced to flee Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia for Tel Aviv in Israel. But he carried Kafka's papers with him in a suitcase, and later went on to publish many of them - helping to posthumously cement his friend's place in history.

Scattered across Europe

Brod's own death 29 years later started what Ms Lion-Yerushalmi called the "Kafkaesque story" of the archive.

Brod left the entire archive to his secretary Esther Hoffe, and asked her to ensure that they reached the National Library.

However, she held on to the papers until her own death in 2007, storing some of them in her apartment in Tel Aviv, and others in vaults in Israel and Switzerland. In 1988, she sold the manuscript of The Trial for $2m.

You may also be interested in:

When Ms Hoffe died, the National Library appealed to her daughters to honour Brod's last wishes and give them the remaining manuscripts. However, their request was refused, and they started legal proceedings the following year.

Eventually, Israel's Supreme Court sided with the library and ordered the papers to be handed over to them.

Then the search began.

Sold, stolen and scratched by cats

After the Supreme Court ruling, the bank vaults in Israel that contained some of the papers were opened, and investigators were allowed to look for more in Ms Hoffe's apartment in Tel Aviv.

When they searched the flat, they found it had been taken over by cats. Some of the papers had been kept in a disused fridge.

Stefan Litt, humanities curator at the National Library, told British newspaper The Telegraph earlier this year that the cats had caused "damage" to the literary documents, external: "Some had been scratched by cats, others had been made wet by cats."

Max Brod left the papers to the National Library of Israel in his will

In 2013, another batch resurfaced when two Israelis approached the German Literary Archives, in the small city of Marbach, saying they had some of Brod's unpublished documents. German police located and seized the papers, and after a court ruling this January, they were returned to Israel.

The fifth and final cache was released after a court ruling in Switzerland in May.

Speaking after its return to the library, Mr Litt told AFP news agency he was grateful to UBS for its "heart-warming" co-operation.

Reflecting on the now-complete collection, he added: "Without Max Brod, we would not really know who Kafka is."

Related topics

- Published9 August 2016

- Published29 June 2019

- Published22 August 2017