Turkey-Syria offensive: What are ‘safe zones’ and do they work?

- Published

The BBC's Martin Patience explains what's behind Turkey's offensive in northern Syria

Russian and Turkish troops have begun patrolling what Turkey says is a "safe zone" in north-east Syria.

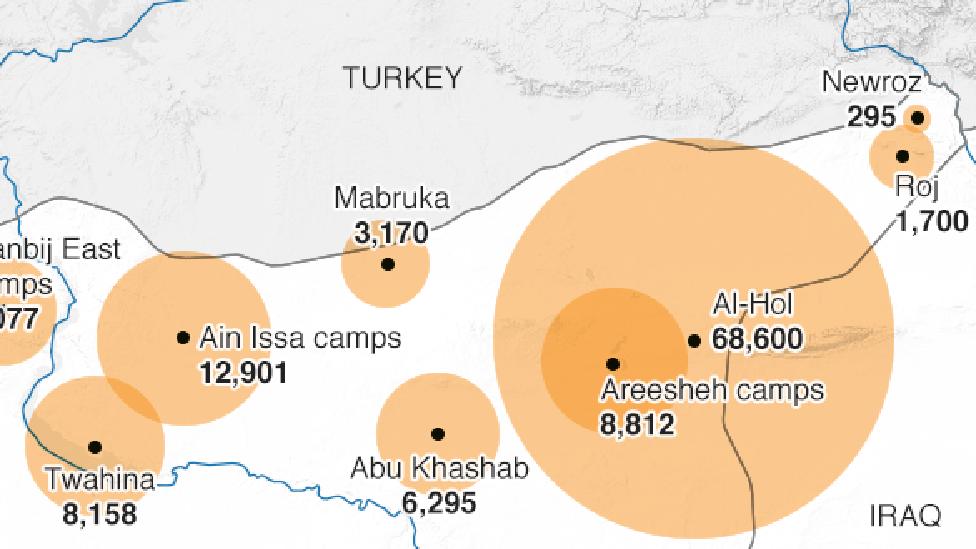

The Turkish plan is designed in part to house Syrian refugees in a secure area along its border with Syria, as well as to keep it free from Kurdish fighters it regards as terrorists.

The concept seems simple, in theory. But in practice - as conflicts from Bosnia and Rwanda to Iraq and Sri Lanka have shown - making safe zones work is more difficult.

What's happening in north-east Syria?

The abrupt withdrawal of US troops from northern Syria last month opened the way for Turkey to launch an offensive across the border.

After days of clashes with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), Turkey agreed to pause for Kurdish fighters to withdraw beyond a range of 30km (18 miles).

Under a new set-up agreed between Turkey and Russia (the main power-broker in Syria), the resulting "safe zone" is to be patrolled by Russian and allied Syrian forces on either side of a stretch held by Turkey and Turkish-backed rebels.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

US President Donald Trump hailed the deal as a "big success", while Germany has floated the idea of using UN troops to guard the zone.

However the track record of safe zones, experts say, does not inspire optimism, and there are fears that the Turkish plan puts Kurds at risk of displacement and ethnic cleansing.

"You can't just displace one million people and put them in a no-man's land," Ahmed Benchemsi, of the international campaign group Human Rights Watch (HRW) , says.

What is a 'safe zone'?

It is common to hear different terms - "safe areas", "protected areas", "humanitarian corridors" and "safe havens" - but they essentially mean the same thing.

The main purpose is to protect civilians fleeing from conflict. HRW defines safe zones as "areas designated by agreement of parties to an armed conflict in which military forces will not deploy or carry out attacks", external.

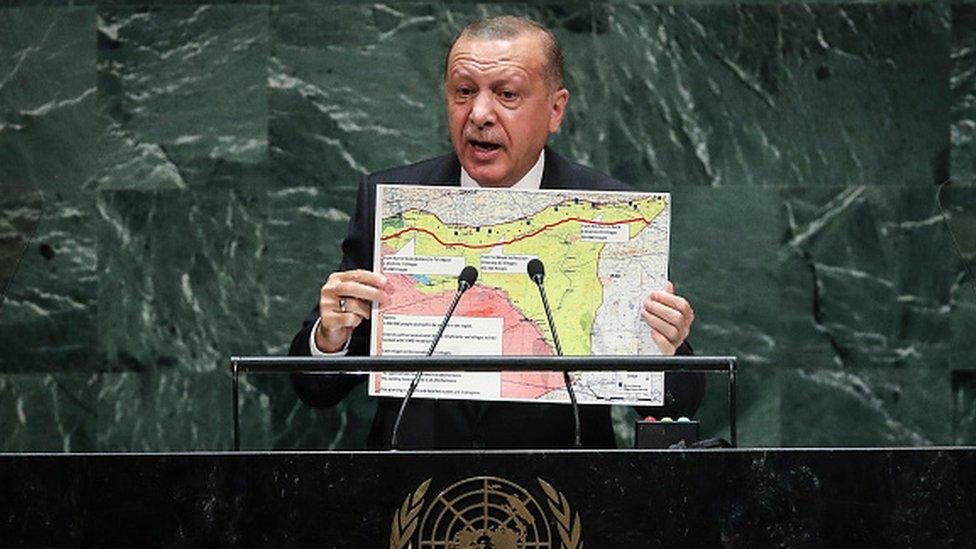

Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, speaking at the UN General Assembly, held up a map of the proposed safe zone

Although they technically differ from "demilitarized zones", which ban military activity and infrastructure, and "no-fly zones", which prohibit military aircraft from operating in the area, they often go hand-in-hand.

This was the case in Iraq after the Gulf War of 1991, when the US, Britain and France declared two no-fly zones in the north and south. They did so in part to protect the Kurdish minority in the north and civilians in the Shia-dominated, whose uprisings against Saddam Hussein had been brutally crushed.

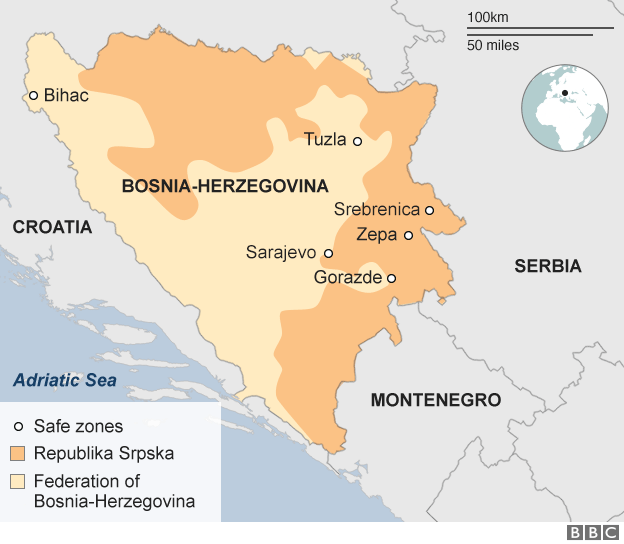

The UN Security Council also has powers to establish safe zones, and has done so in the past in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1993 and Rwanda in 1994.

Safe zones sound like a good idea, so what's the problem?

Few would argue that the concept of creating a haven for civilians in a conflict zone is not commendable. In theory, in these "protected" areas, displaced people have better access to food, shelter, medical care and security than anywhere under fire.

It is also claimed that safe zones prevent mass migration into neighbouring countries, where they would place strain on infrastructure and fuel political tension. It is also argued that refugees prefer to be placed in a safe zone within their country of origin, where they are familiar with the culture, language and social norms.

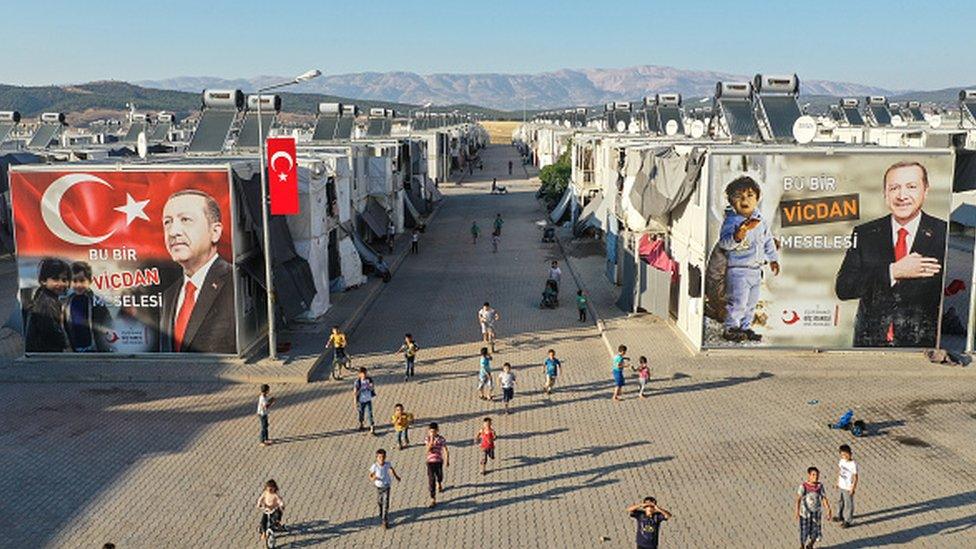

The Turkish Red Crescent camp, pictured here, hosts nearly one million displaced Syrians along the Turkish-Syrian border

Syrian refugee children play in front of a poster of Turkey's president at a refugee camp in Kahramanmaras, Turkey

However, a conflict is not fertile territory for agreement between warring sides to hold, and if a deal breaks down, civilians who have fled there to escape fighting are again put at risk of attack.

"Calling something safe does not make it so," Prof David Keen, author of a paper on the problems of "safe zones", external, told the BBC.

HRW has also warned that Turkey's zone would be 'anything but safe', external, risking new waves of displaced people and lacking infrastructure to cope with large numbers of returnees.

Experts say motives behind the creation of safe zones are not always humanitarian

"Frequently, and perhaps inevitably, [safe zones] have security problems," says Mr Benchemsi.

He says a large civilian population of a particular ethnic or religious group may be vulnerable to attack along sectarian lines.

There is also the risk, he says, that armed fighters will mingle with civilians, turning the safe zone into a legitimate military target. And thirdly, he says, civilians outside the safe zone may be seen as "fair game".

What happened with other 'safe zones'?

In many cases, safe zones have, ironically, proved distinctly dangerous. While there are some examples of success, they have in some instances been blamed for costing rather than saving lives.

"When we look at history, safe zones created in mass conflicts have rarely been actually safe," Mr Benchemsi says.

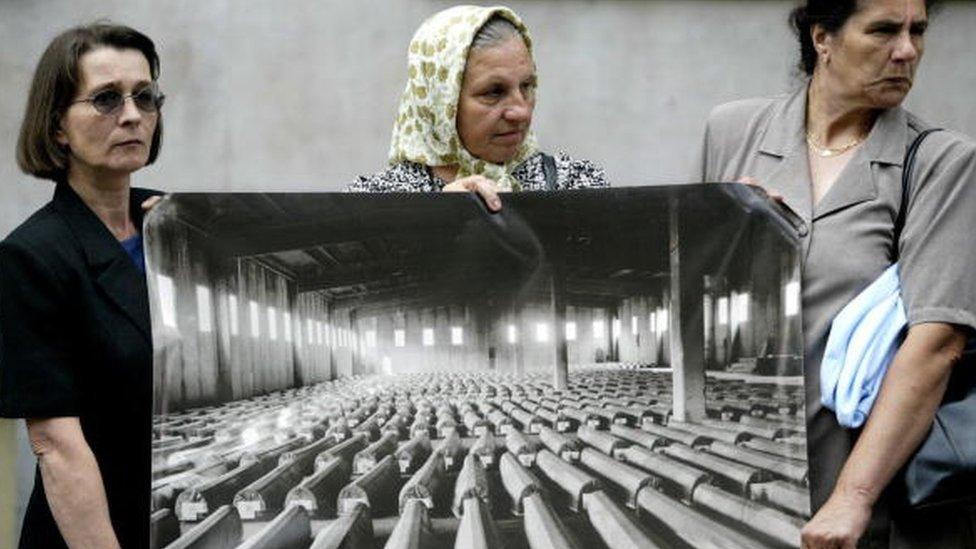

Survivors and relatives of victims of the Srebrenica massacre hold a picture of coffins at a protest in 2004

The most infamous failure happened during the Bosnian War in 1995. The war pitted Bosnian Serbs against the Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) army, which wanted Bosnia-Herzegovina to break away from the former Yugoslavia. At the height of the conflict, in 1993, the UN declared six safe zones, which were put under the protection of peacekeeping forces.

One of the safe zones was in the town of Srebrenica, where thousands of Muslims sought safety at a lightly defended UN compound.

When the town fell during a Bosnian Serb offensive led by Gen Ratko Mladic, the UN peacekeepers surrendered. More than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were subsequently massacred by Bosnian Serb troops in what was later called the deadliest atrocity in Europe since World War Two, external.

"When such zones are created and the protection is not forthcoming, the results can be catastrophic," Lynn Maalouf, Middle East research director for Amnesty International, says.

As in Srebrenica, bloodshed followed the creation of a safe zone during the Rwandan civil war in 1994. The mass slaughter of the Tutsi minority by Hutu extremists prompted a UN-backed intervention by the French military. A safe zone set up by the French was supposed to protect displaced civilians.

When the conflict ended in 1994, the Tutsi-led Rwandan government sent in the army to disperse refugees at one camp in Kibeho, where Hutu militia implicated in the genocide were thought to be hiding.

Troops committed a massacre, killing hundreds of refugees with machine guns and grenades, external. Once again, UN peacekeepers were helpless to stop the killing.

A UN peacekeeper stands at the entrance of the Kibeho refugee camp in Rwanda

There was a similar outcome in Sri Lanka, where the government fought a 26-year civil war against the Tamil Tigers, a rebel group.

In 2009, as the conflict neared its end, the government told civilians to seek shelter from the fighting in designated safe zones. But the UN accused government forces of continuing to bombard civilian areas, including the safe zones. The government denied deliberately targeting the safe zones, saying it was responding to rebel fire.

Thousands died as "a direct consequence of declaring a safe zone", Mr Benchemsi says.

In contrast, the no-fly zones in northern and southern Iraq were considered effective, insofar as they protected Kurds and Shia Muslims from Saddam Hussein's forces.

But without approval from the UN Security Council, they lacked international legitimacy, and the extent to which they saved lives has also been questioned. When the no-fly zones were in force, the US, France and Britain were accused of killing hundreds of Iraqi civilians during bombings.

As these cases show, safe zones have a controversial history. Results have been mixed. Experts agree that good intentions don't always amount to good outcomes.

This is because the motives behind safe zones are complex, Stefanie Kappler, a professor of conflict resolution at Durham University, says.

"The establishment of safe zones is rarely purely altruistic," she contends. "Safe zones often serve to protect powerful states from refugee inflows or as a means to justify sending asylum-seekers back to a zone of alleged safety.

"There is certainly a highly political angle to deciding who qualifies as a victim of war and who is deemed worthy of protection."

- Published18 October 2019

- Published14 October 2019

- Published23 October 2019