Idlib before the war: Carpets, olives and handcrafts

- Published

Idlib was especially famous for its olive groves

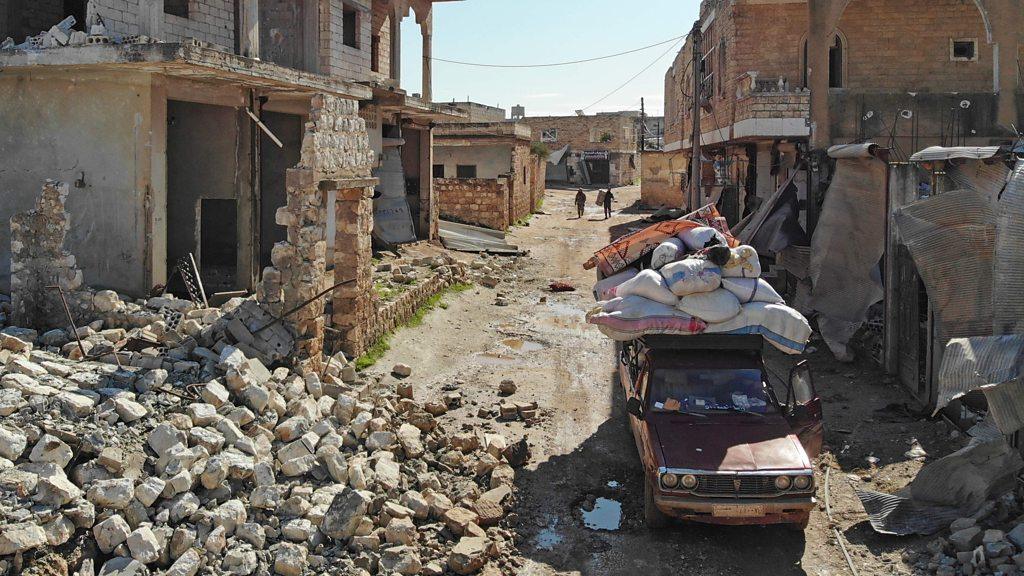

The last rebel-held province in Syria - Idlib - has been devastated by years of war and the displacement of millions of people.

Here two residents recall what Idlib was like as a place to live when Syria was at peace.

Saad

Before the revolution, Idlib was famous for olive trees and olive oil - lots of Syrian provinces got their olive oil from Idlib.

Citizens here used to work in agriculture and in planting olive trees. They would pickle olives and sell them locally and to Arab states such as Iraq.

We also had lots of people who made carpets, glass and other handcrafts.

Syria War: Why is Idlib back in the news?

The city was famous for the ruins of [the ancient city of] Ebla in the east. Tourists and archaeologists from all over the world visited them.

We remember our schools and our friends who have died or emigrated. Every person here still has some of their old friends but most memories have been destroyed by the war and we have lost a lot of dear people.

A lot of things have changed for us. The biggest difference is in the state of our lives. We only have electricity for about three hours a day now. We live on generators which provide power.

There is a lack of water and there is no cleanliness or rubbish disposal. The streets are always dirty and there are no street lights.

We miss hanging out at night, being able to walk in a well-lit street and spend the whole night there with friends, laughing and eating. We can't do any of this anymore.

The moment the revolution started [in 2011], I knew that things would change in the country, but I didn't expect it to change for the worse.

Idlib has lost its people, lost the children playing outside, the families that lived here for generations. A lot of people came here to escape other parts of the country where there was fighting, but the city misses its sons and daughters who were born and bred here.

Salwa

One of the most memorable moments for me growing up in Idlib was when former President Hafez al-Assad came to power [in 1971] and visited Idlib. He was attacked by people who threw tomatoes at him. In retribution, the city was excluded from many things such as infrastructure projects, social development and even political participation.

What it's like inside the last rebel stronghold in Syria

We were never able to speak about politics. Elders used to tell us to shut up and that politics was not our business, every time we tried to voice our concerns.

During school, we were forced to join the Baath [ruling party] scouts. We could not refuse, we had to do this, everyone had to. They used to treat us as if we were an army. We were punished for every mistake. It might have been good to make us stricter and tougher in life, but in my opinion the negatives outweighed the benefits.

Idlib was one of the first cities to start the revolution. Most of the city's people are known for their opposition to [President Bashar al-] Assad and that's why we were scared. We all know how Idlib's people welcomed his father.

At the beginning of the revolution, I lived in Aleppo and I watched on TV what was happening. There were a lot of images which portrayed the rebels as criminals. But when I came into the city, I saw that those were lies from the government media. Therefore, I started to become an activist but without revealing it to anyone.

In 2012, there were attacks on the area where I was living in in Aleppo, so I moved back to Idlib and then I started to participate more in the activities. When the rebels took over the city, my participation in the revolution became public.

Idlib has changed between my childhood and now. Now we are free, before we lived in fear and said "the walls have ears". We used to be afraid to speak and now there is more expression and freedom.

Even though we are subjected to death, air strikes and murder, the revolution still lives with us.

I have changed dramatically since the revolution. I know all about politics. We used to only study about the Baath party and its rule, but now I know about elections, about running in elections, the duties of the president, democracy.

I don't have any pictures or anything left of my younger days and this is because I took them with me to Aleppo and I had to flee from the war and couldn't bring them back with me to Idlib. This hurts so much.

What hurts me most is that I didn't expect not to be able to go back. I had pictures of my kids and my husband, and I will never get any of them back.

Interviews by Abd Alkader Habak, BBC.

- Published28 February 2020

- Published24 February 2020

- Published11 February 2020

- Published8 February 2020

- Published18 February 2020

- Published18 February 2020

- Published30 January 2020