Lebanon: Why the country is in crisis

- Published

Lebanon is in the throes of its worst crisis for many years

The Lebanese government has resigned amid growing public anger following a devastating explosion in Beirut on 4 August that killed at least 200 people and injured about 5,000 others.

The blast came at a difficult time for Lebanon, which is not only trying to curb the spread of the coronavirus but is also mired in an unprecedented economic crisis.

The economic situation has pushed tens of thousands people into poverty and triggered large anti-government protests.

Why did the government resign?

Announcing the move on Monday, outgoing Prime Minister Hassan Diab said his government was taking "a step back... to stand with the people, in order to wage the battle of change with them".

Discontent in Lebanon has been brewing for years. In late 2019, a plan to tax Whatsapp calls spilled over into mass protests against economic turmoil and corruption, which eventually led to the then government's resignation.

Coronavirus had curbed the protests, but the financial situation continued to worsen and last week's deadly explosion was seen by many as the deadly result of years of corruption and mismanagement.

People have taken to the streets again, and there have been clashes between protesters and police.

The government's plans to investigate the cause of the explosion were not enough for most people, who have lost all faith in the political elite. Before the cabinet's resignation, a number of ministers had offered to step down.

But the end of this government does not necessarily mean an end to the anger. Last year's protests led to the formation of the government which has now been forced to step down over the same accusations of corruption.

In his strongly worded speech on Monday, Mr Diab blamed "a system of corruption... deeply-rooted in all the functions of the state".

"One of the many examples of corruption exploded in the port of Beirut, and the calamity befell Lebanon," he said.

"But corruption cases are widespread in the country's political and administrative landscape; other calamities hiding in many minds and warehouses, and which pose a great threat, are protected by the class that controls the fate of the country."

What went wrong with the economy?

Even before the coronavirus pandemic at the start of this year, Lebanon seemed to be headed for a crash.

Its public debt-to-gross domestic product (what a country owes compared to what it produces) was the third highest in the world; unemployment stood at 25%; and nearly a third of the population was living below the poverty line.

The Lebanese pound has lost about 80% of its value over the past 10 months

Late last year also saw the unravelling of what analysts said was effectively a state-sponsored pyramid, or Ponzi, scheme, external run by the central bank, which was borrowing from commercial banks at above-market interest rates to pay back its debts and maintain the Lebanese pound's fixed exchange rate with the US dollar.

At the same time, people were getting increasingly angry and frustrated about the government's failure to provide even basic services. They were having to deal with daily power cuts, a lack of safe drinking water, limited public healthcare, and some of the world's worst internet connections.

Many blamed the ruling elite who have dominated politics for years and amassed their own wealth while failing to carry out the sweeping reforms necessary to solve the country's problems.

Why did protests escalate?

At the start of October 2019, a shortage of foreign currency led to the Lebanese pound losing value against the dollar on a newly emerged black market for the first time in two decades. When importers of wheat and fuel demanded to be paid in dollars, unions called strikes.

Then, unprecedented wildfires in the country's western mountains highlighted how underfunded and underequipped the fire service was.

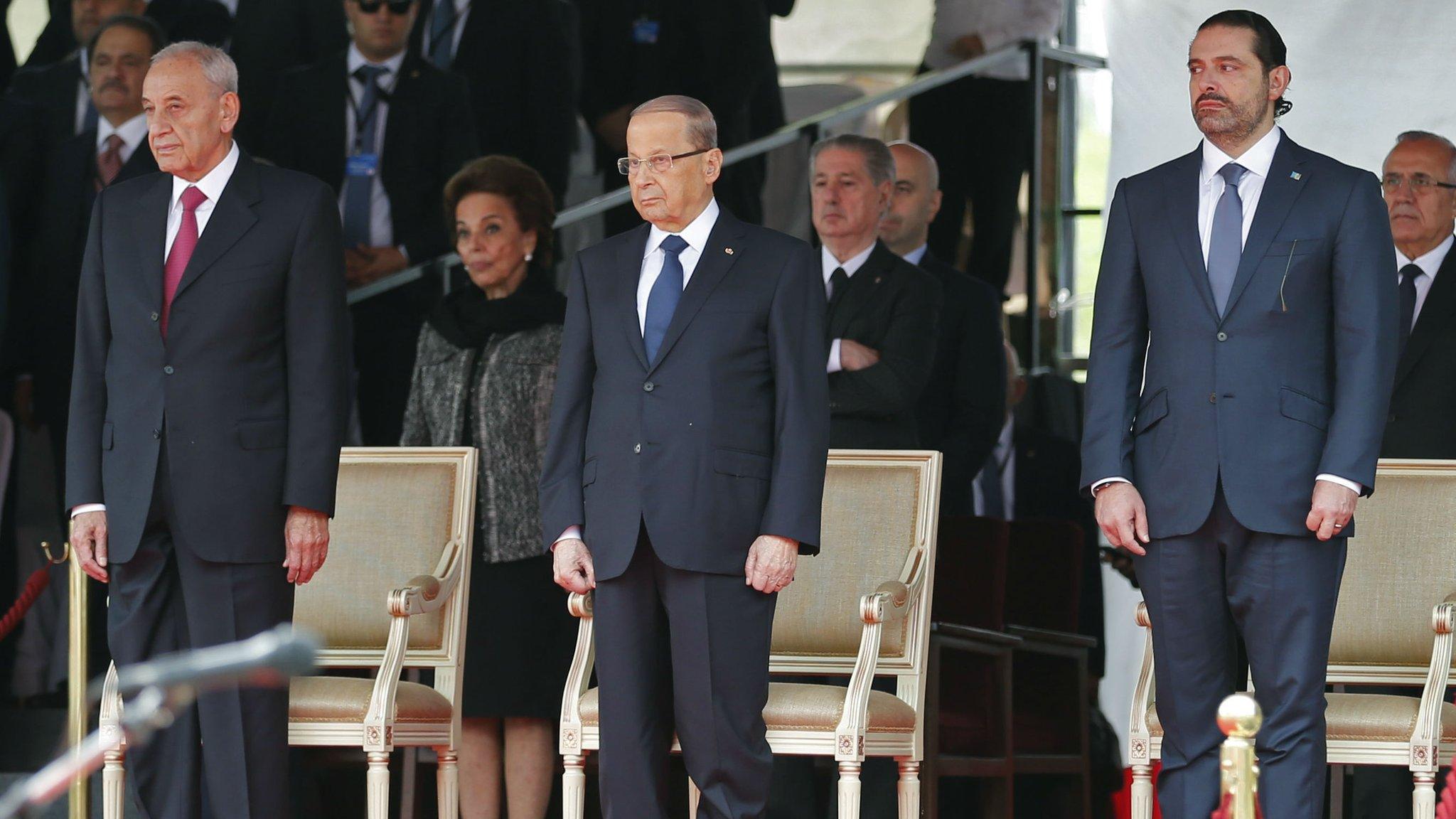

Saad Hariri resigned as prime minister in response to the protests

In mid-October, the government proposed new taxes on tobacco, petrol, and voice calls via messaging services such as WhatsApp to drum up more revenue, but a backlash forced it to cancel the plans.

However, the debacle unleashed a surge of discontent that had been simmering in Lebanon for years.

Tens of thousands of Lebanese took to the streets, leading to the resignation of Western-backed Prime Minister Saad Hariri and his unity government.

The protests have cut across sectarian lines and involved people from all sections of society

Protests cut across sectarian lines - a rare phenomenon since the country's devastating 1975-1989 civil war ended - and brought the country to a virtual standstill.

Newly appointed Prime Minister Hassan Diab subsequently announced that Lebanon would default on its foreign debt for the first time in its history, saying its foreign currency reserves had hit a "critical and dangerous" level and that those remaining were needed to pay for vital imports.

How has the pandemic made matters worse?

In the wake of the first Covid-19 deaths and a surge in infections, a lockdown was imposed in mid-March to curb the spread of the disease.

On the one hand, it forced anti-government protesters off the streets, but on the other, it made the economic crisis much worse and exposed the inadequacies of Lebanon's social welfare system.

The prime minister has warned that Lebanon is at "risk of a major food crisis"

Many business were forced to lay off staff or put them on furlough without pay; the gap between the Lebanese pound's value on the official and black-market exchange rates widened; and banks tightened capital controls.

As prices rose further, many families were unable to buy even basic necessities.

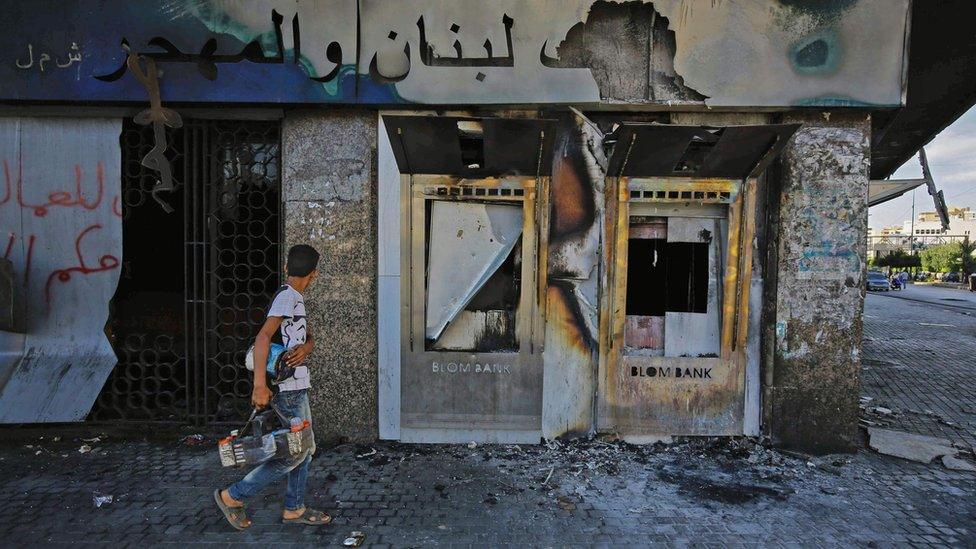

Growing economic hardship triggered fresh unrest. In April a young man was shot dead by soldiers during a violent protest in Tripoli and several banks were set ablaze.

The government, meanwhile, finally approved a recovery plan that it hoped would end the economic crisis and win support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout package worth $10bn.

Banks have been attacked and set on fire by protesters

By the time the coronavirus restrictions began to be lifted in May, the prices of some foodstuffs had doubled and Mr Diab warned that Lebanon was at risk of a "major food crisis".

"Many Lebanese have already stopped buying meat, fruits and vegetables, and may soon find it difficult to afford even bread," he wrote in the Washington Post.

Why is Lebanon struggling to do anything about it?

Most analysts point to one key factor: political sectarianism, or groups looking after their own interests.

Lebanon officially recognises 18 religious communities - four Muslim, 12 Christian, the Druze sect and Judaism.

The three main political offices - president, speaker of parliament and prime minister - are divided among the three biggest communities (Maronite Christian; Shia Muslim; and Sunni Muslim, respectively) under an agreement dating back to 1943.

Parliament's 128 seats are also divided evenly between Christians and Muslims (including Druze).

The seats in parliament are divided between religious communities

It is this religious diversity that makes the country an easy target for interference by external powers, as seen with Iran's backing of the Shia Hezbollah movement, widely seen as the most powerful military and political group in Lebanon

Since the end of the civil war, political leaders from each sect have maintained their power and influence through a system of patronage networks - protecting the interests of the religious communities they represent, and offering - both legal and illegal - financial incentives.

Lebanon ranked 137th out of 180 countries, external (180 being the worst) on Transparency International's 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index.

The watchdog says corruption "permeates all levels of society" in Lebanon, with political parties, parliament and the police perceived as "the most corrupt institutions of the country".

It says it is the very system of sectarian power-sharing which is fuelling these patronage networks and hindering Lebanon's system of governance.

- Published12 June 2020

- Published27 May 2020

- Published13 May 2020

- Published4 May 2020

- Published5 March 2020

- Published13 December 2019

- Published7 November 2019

- Published25 October 2019