How the UAE emerged as a regional powerhouse

- Published

A Yemeni fighter stands next to a mural of the UAE's late founder, Sheikh Zayed Al Nahyan

2020 has been quite a year for the United Arab Emirates - the small but super-rich and mega-ambitious Gulf nation.

It has sent a mission to Mars; struck a historic peace deal with Israel; and managed to get sufficiently ahead of the curve on Covid-19 that the former British protectorate has retooled factories and sent Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to the UK by the planeload.

It has also found itself embroiled in a costly strategic struggle for influence with Turkey as it stretches its tentacles as far afield as Libya, Yemen and Somalia.

So with its 50th anniversary since its independence coming up next year, what exactly is the UAE's global game and who's driving it?

Chance meeting

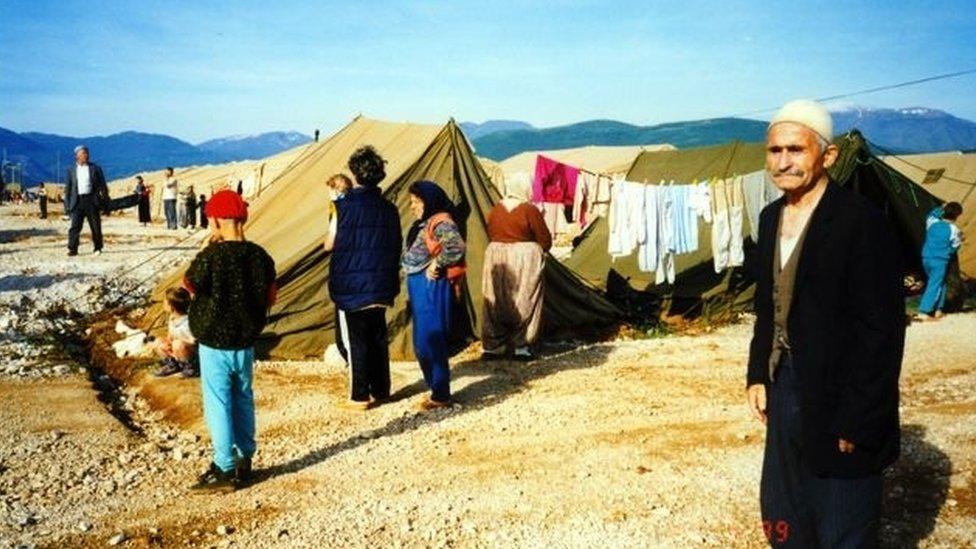

It's May 1999 and the Kosovo war has been raging for over a year. I am standing at a wash basin inside a makeshift hut at a well-defended camp on the Albanian-Kosovo border, a place packed with Kosovar refugees.

The camp has been set up by the Emirates Red Crescent Society and the Emiratis have arrived with a full coterie of cooks, halal butchers, telecoms engineers, an imam, and a contingent of troops who are patrolling the perimeter in desert-camouflage Humvees mounted with heavy machine-guns.

We had flown up the previous day from Tirana in Puma helicopters flown by UAE Air Force pilots through the twisting, rugged ravines of north-east Albania.

The UAE set up a camp for displaced Kosovans on the Kosovo-Albanian border in the late 1990s

The man now brushing his teeth at the basin next to me is tall, bearded, bespectacled. I recognise him as Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, a graduate of Britain's Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and the driving force behind the UAE's expanding military role.

Could we do a TV interview, I ask? He is not keen, but agrees.

The UAE, he explains, has entered into a strategic partnership with France. As part of a deal to buy 400 French Leclerc tanks, the French are taking a brigade of Emirati troops "under their wing", training them up in France to deploy alongside them in Kosovo.

For a country that had only gained its independence less than 30 years earlier it was a bold move. There, in that remote corner of the Balkans, we were more than 2,000 miles (3,200 km) from Abu Dhabi, yet the UAE clearly had ambitions far beyond the shores of the Gulf.

It had become the first modern Arab state to deploy its military in Europe, in support of Nato.

'Little Sparta'

Next came Afghanistan. Unknown to most of the UAE's population, Emirati forces began quietly operating alongside Nato there soon after the fall of the Taliban in a move sanctioned by the now Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Zayed.

In 2008, I visited a contingent of their special forces at Bagram Airbase and saw how they operated.

Travelling in Brazilian and South African armoured vehicles, they would drive into a remote and impoverished Afghan village, distribute free Korans and boxes of sweets, then sit down with the elders.

UAE special forces personnel were deployed to Afghanistan

"What do you need?" they would ask. "A mosque, a school, wells drilled for drinking water?" The UAE would put up the money while the contracts went out to local tender.

The Emiratis' footprint was small, but wherever they went they used money and religion to try to reduce the widespread local suspicion of the often heavy-handed Nato forces.

In Helmand province they also fought alongside British forces in some intense firefights. The former US Defence Secretary, Jim Mattis, later dubbed the UAE "Little Sparta", in reference to this relatively little-known country, with a population of less than 10 million, punching well above its weight.

Yemen: A damaged reputation

Then came Yemen and a military campaign that has been fraught with difficulties.

When Saudi Arabia's Prince Mohammed bin Salman took his country into Yemen's disastrous civil war in 2015, the UAE joined in, sending its F-16 fighters to conduct air strikes against the Houthi rebels and sending its troops to the south.

In the summer of 2018 it landed troops on the strategic Yemeni island of Socotra and amassed an assault force at a leased base at Assab in Eritrea, baulking at the last minute from sending them across the Red Sea to retake the port of Hudaydah from the Houthis.

The war in Yemen has now dragged on for almost six years, there are no clear winners and the Houthis remain firmly entrenched in the capital, Sanaa, and much of the country.

Emirates Red Crescent Society workers hand out aid in Socotra, Yemen

The UAE's forces have taken casualties, including more than 50 in a single missile strike, resulting in three days of national mourning back home.

The UAE's reputation has also been damaged by its association with some unsavoury local militias linked to al-Qaeda and reports from human rights campaigners that UAE associates locked dozens of prisoners inside a shipping container, where they suffocated to death in the heat.

Israel: A new alliance

The UAE has since reduced its involvement in Yemen's inconclusive and destructive conflict, but it continues to stretch its military tentacles far and wide in a controversial bid to push back Turkey's growing influence across the region.

So while Turkey has a substantial presence in the Somali capital Mogadishu, the UAE is supporting the breakaway territory of Somaliland and has built a base at Berbera on the Gulf of Aden.

In war-torn Libya, the UAE has joined Russia and Egypt in supporting the forces of Khalifa Haftar in the East against those in the West who are supported by Turkey, Qatar and others.

"A threat to the viability of the two state solution" brought plans forward, says Anwar Gargash

This September, the UAE sent ships and fighter jets to the island of Crete for joint exercises with Greece, as that country squared up for a possible confrontation with Turkey over drilling rights in the eastern Mediterranean.

And now, after a sudden, dramatic announcement from the White House, there is a wide-reaching UAE-Israel alliance, putting an official seal on years of covert co-operation. (Like Saudi Arabia, the UAE has been quietly acquiring intrusive Israeli-made surveillance software to keep an eye on its citizens).

While the alliance embraces a wide spectrum of healthcare, biotech, cultural and trade initiatives, it also has the potential to create a formidable strategic military and security relationship, harnessing Israel's cutting-edge technology with the UAE's bottomless pockets and global aspirations.

The two countries' common enemy, Iran, has condemned the accord, as have Turkey and the Palestinians, accusing the UAE of betraying Palestinian aspirations for an independent state.

Reaching for the stars

Abu Dhabi's ambitions do not end there. With US help, it has become the first Arab nation to send a mission to Mars.

In a $200m (£156m; 170m euros) programme dubbed "Hope", its spacecraft is already hurtling through space at 126,000km/h (78,000mph) after taking off from a remote Japanese island.

It is due to reach its destination, 495 million km away, in February. Once there, it will map the atmospheric gases that surround the red planet, sending the data back to Earth.

A rocket carrying the UAE's Mars probe lifted off from Japan in July

"We want to be a global player," says the UAE's Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Anwar Gargash. "We want to break barriers and we need to take some strategic risks to break these barriers."

However, there are concerns that by moving so fast and so far, the UAE risks overreaching itself.

"There's little doubt the UAE is the [Arab] region's most effective military power," says Gulf analyst Michael Stephens.

"They are able to deploy forces far overseas in ways that other Arab states simply cannot do. But they are also limited by size and capacity, and taking on so many problems at once is risky, and in the long run could end up backfiring."

- Published15 September 2020

- Published15 September 2020

- Published15 September 2020

- Published2 September 2020

- Published31 August 2020

- Published18 August 2020

- Published16 August 2020

- Published14 August 2020

- Published13 August 2020

- Published2 August 2020

- Published20 July 2020

- Published14 July 2020

- Published18 May 2020

- Published7 September 2023