US election: Gulf Arab leaders face new reality after Biden victory

- Published

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed are close Trump allies

"You'll have to forgive me if I seem a little distracted," said the Saudi ambassador to the UK as his eyes flicked towards his mobile phone. "I'm keeping an eye on the results coming in from Wisconsin."

That was eight days ago, when we still did not know who would be in the White House in January.

When Joe Biden was declared the winner, the Saudi leadership in Riyadh took rather longer to respond than they did when Donald Trump was elected.

This is hardly surprising: they had just lost a friend at the top table.

Mr Biden's victory could now have far-reaching consequences for Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf Arab states.

The US strategic partnership with the region goes back to 1945 and it will likely endure, but changes are coming and they will not all be welcome in Gulf capitals.

Losing a major ally

President Trump was a massive ally and supporter of Saudi Arabia's ruling Saud family.

He chose Riyadh as the destination for his first foreign presidential visit after taking office in 2017.

His son-in-law, Jared Kushner, formed a close working relationship with the all-powerful Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

When every major Western intelligence agency suspected the crown prince of being behind the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018, President Trump refused to blame him outright.

Saudi Arabia was the destination of Donald Trump's first foreign trip as US president

Little wonder that MBS's team told people in the days immediately afterwards: "Don't worry, we've got this."

Mr Trump also resisted strident calls in Congress to curb arms sales to the Saudis.

So Saudi Arabia, and to a lesser extent the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, are about to lose a major ally in the White House.

Plenty of things will not change but here is a look at some of the things that are likely to.

The Yemen war

President Barack Obama, under whom Mr Biden served as vice-president for eight years, was increasingly uncomfortable about Saudi Arabia's conduct of the war against Yemen's Houthi rebels.

By the time he left office, the air war had been going for almost two years with little military success while inflicting enormous damage on civilians and the country's infrastructure.

A Saudi-led coalition of Arab states is backing Yemen pro-government forces

Alert to the war's unpopularity on Capitol Hill, President Obama cut back on US military and intelligence aid to the Saudi war machine.

The Trump administration reversed that move and effectively gave the Saudis a free hand in Yemen.

Now it looks set to flip back again, with Mr Biden recently telling the Council on Foreign Relations that he would "end US support for the disastrous Saudi-led war in Yemen and order a reassessment of our relationship with Saudi Arabia".

Pressure from an incoming Biden administration on the Saudis and their Yemeni allies to settle this conflict is now likely to increase.

The Saudis, and the Emiratis, realised some time ago this was never going to end in a military victory and have themselves been looking for a face-saving exit that does not leave the Houthis in exactly the same place they were when the air war started in March 2015.

Iran

President Obama's one big legacy in the Middle East was the hard-won Iran nuclear deal - the so-called Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

This lifted sanctions on Iran in return for strict compliance with limits on its nuclear activities and inspections of its nuclear facilities.

President Trump called it "the worst deal ever" and pulled the US out of it.

Now, his successor looks set to take the US back into the agreement in some form.

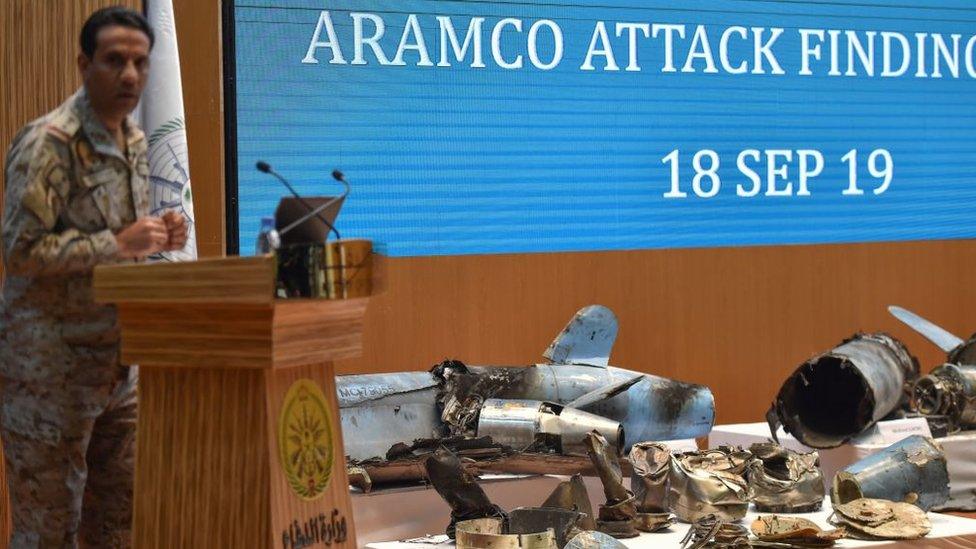

Saudi Arabia accused Iran of drone and cruise missile attacks on two key oil facilities in 2019 - a charge Tehran denied

This appals the Saudis. In Riyadh last autumn, shortly after the mysterious missile attacks on Saudi Arabia's petrochemical plants, I attended a press conference by the kingdom's Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Adel al-Jubeir, who lambasted the Iran nuclear deal.

It was disastrous, he said, as it did not take into account (it was never meant to) Iran's expansive strategic missile programme nor the proliferation of its proxy militias across the Middle East.

The whole deal, he implied, was part of the flawed legacy of an Obama administration that had not appreciated the extent of the danger posed by the Islamic Republic.

The Saudis and some of their Gulf allies quietly applauded when in January this year the US carried out a drone strike in Iraq that assassinated Gen Qasem Soleimani, the commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards' overseas operations arm, the Quds Force.

Now they worry whether the incoming White House team will be tempted to make a bargain with Tehran that undercuts their own interests.

Qatar

Qatar is home to the Pentagon's largest and most strategically important base in the Middle East: Al-Udeid Air Base.

From there, the US directs all its air operations in the Central Command region, from Syria to Afghanistan.

And yet Qatar is still under a damaging boycott from a quartet of Arab states - Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt - who are all furious at its support for political Islamist movements like the Muslim Brotherhood.

Donald Trump invited Qatar's Emir, Sheikh Tamim Al Thani, to the White House last year

The boycott began shortly after President Trump's much-trumpeted visit to Riyadh in 2017, and the quartet clearly thought they had his backing.

In fact, Mr Trump initially and briefly supported it publicly until it was explained to him that Qatar was also a US ally and that Al-Udaid was rather important to the US defence department.

President-elect Biden's administration is likely to push for this inter-Gulf rift to be healed. It has not been in the interest of the US, and it certainly has not been in the interests of the Gulf Arab states themselves.

Human rights

Several of the Gulf states have poor human rights records.

But President Trump never showed much interest in castigating his Arab allies on the issue.

US intelligence services reportedly concluded that Saudi Arabia's crown prince ordered the killing of Jamal Khashoggi

He argued that US strategic interests and business deals overrode any concerns about imprisoned women's rights campaigners; the alleged abuse of foreign labourers in Qatar; or the fact that in October 2018 Saudi government security men flew in official planes to Istanbul to carry out a pre-planned operation to silence Saudi Arabia's most vocal critic, Jamal Khashoggi, disposing of his body which has never been found to this day.

President-elect Biden and his administration are unlikely to be so forgiving.