Yemen: This doctor saw Covid hospital empty after fake death text

- Published

As war-torn Yemen braces itself for a second wave of Covid-19, one doctor recalls how she battled the pandemic alone after her colleagues fled the hospital, and the dramatic fake news that plagued the assistance when it eventually arrived.

Twenty-nine-year-old Zoha Aidaroos al-Saadi recalls the moment she stood behind a hastily painted red quarantine line down the middle of her hospital. A patient on the other side of the line was all alone, struggling to breathe.

For weeks, the line had not been needed. It was only a quiet warning that the pandemic ravaging other nations would eventually reach Yemen. But now al-Amal hospital, in the southern city of Aden, had its first suspected coronavirus patient.

Zoha hovered at the line, terrified. The rest of the medical staff stood there too. When she asked them what was happening, they said they had given the man oxygen but wanted no further contact with him. The next thing she knew, her colleagues had left the hospital completely.

"There was no response. I kept calling and shouting out… There was nobody left." Management say, however, that they did not leave the hospital.

Find out more

Nawal al-Maghafi was the first reporter to enter Yemen since the outbreak of Covid-19. Watch her documentary Yemen: Coronavirus in a Warzone is on BBC 2 at 23:30 GMT on Monday 18 January and also available on iPlayer

For the next two weeks, Zoha and a single nurse were alone with dozens of patients.

She didn't blame her colleagues. Al-Amal, though designated by the government as the city's official Covid hospital, was completely ill-equipped for that role. It did not have enough PPE, barely any oxygen canisters, and only seven ventilators. During those first two weeks, she was unable to save a single patient.

There has been no social distancing on Yemen's streets

Zoha had been dreading the moment the pandemic would hit Yemen. As she and her mother had watched the news the previous month, glued to the TV as coronavirus tore through the world's most developed nations, her thoughts had immediately turned to home.

Six years of war in Yemen have had a devastating impact. More than half of the country's health facilities have been destroyed and two thirds of the population are reliant on aid to survive.

Yemen's conflict

In 2014, rebels known as Houthis belonging to a branch of Yemen's minority Shia Muslim community seized the capital, Sanaa.

President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi set up a temporary capital in the southern city of Aden before fleeing to neighbouring Saudi Arabia. In 2015, Saudi Arabia and eight other mostly Sunni Arab states began an air campaign against the Houthis, whom they claimed were armed by regional rival Iran. The Saudi-led coalition has received logistical support from the US, UK and France.

There have even been clashes between those ostensibly on the same side. In August 2019 fighting erupted in the south between Saudi-backed government forces and an allied southern separatist movement, the Southern Transitional Council (STC), which has accused President Hadi of mismanagement and links to Islamists.

Militants from al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the local affiliate of the rival Islamic State group (IS) have taken advantage of the chaos by seizing territory in the south and carrying out deadly attacks, particularly in Aden.

But neither the authorities nor the state broadcaster made any mention of Covid. This somehow reassured Zoha. 'If they aren't talking about it,' she told herself, 'perhaps they do have everything under control.'

Even so, when she heard that the World Health Organization was organising a Covid training conference in the country, she decided to sign up. Attendees were taught how to protect themselves and treat Covid patients safely. But although Zoha found the training useful, she was terrified. She knew the real state of the hospitals in Yemen, and particularly the one in Aden where she would be working.

"They were training us but we didn't have the supplies or the infrastructure to apply any of this training."

It was not long before Covid appeared to have spread throughout Aden. As other hospitals in the city found themselves unable to cope, and more than a dozen doctors working in those hospitals themselves died with suspected Covid-19, they shut their doors.

Queuing at the gates

Ambulances and cars driven by patients' relatives flooded al-Amal's hospital car park, all waiting for beds to become available.

There were just nine beds in Zoha's makeshift Covid ward. Each had its own oxygen cylinder, but when they ran out, there was no support staff to refill them. That was down to Zoha and the nurse.

But on many occasions, in the midst of the crisis, they were unable to do so, and patients would suffocate.

Zoha recalls one patient watching her as she desperately tried to keep up with the demands of the ward - his oxygen canister had run out.

"He could see that I was panicking. He held my hand and told me, 'Don't worry my dear, I know my time has come and it is not your fault, you have done all you can.'" He died a few hours later.

Zoha kept reaching out to the government for help, both contacting it directly and posting appeals on Facebook, but got no response.

By May, there were so many international media reports on the effect of coronavirus in Yemen that the government was finally forced to acknowledge the gravity of the situation. It reached out to the NGO Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) for help.

Within days, MSF was in Aden and had taken over the running of al-Amal hospital, bringing both manpower and much-needed supplies. It also set up a makeshift Covid hospital in a wedding hall next door.

MSF arrived in al-Amal hospital in May and quickly made a difference

Zoha was no longer alone.

"I was outside crying, it was all too much," says Zoha. She says an MSF doctor saw her, and uttered the words she says she had been waiting to hear from her own government: "Be strong - we are with you, and the situation will get better, I promise."

With someone now in control and providing guidance and support, the hospital's local staff also returned.

"Patients used to leave the hospital in a white plastic bag, now they [were] walking out. It was like moving from hell to heaven," Zoha told me.

Zoha finally had support when MSF arrived

But this respite was to be short lived. Trouble was brewing. A voice recording shared on WhatsApp went viral in Aden. In the recording, the narrator said MSF staff at al-Amal hospital were killing Covid patients with a lethal injection.

"It was just words without evidence," a local doctor who wished to remain anonymous told me. "They said if someone was terminally ill and about to die, they were given euthanasia injections. It was crazy but the people believed it."

Zoha and MSF both say that numbers of patients appearing for treatment at the hospital dramatically declined following the recording. One patient, struggling to breathe, told Zoha he had had to beg his brothers to bring him to the hospital because they all believed that, once there, he would be euthanised.

Clashes in the hospital

And the unhelpful rumours kept coming, the doctors say. At one point, a number of armed men forced their way into the hospital. Local staff allege they were threatened. The armed men were led into the hospital - local staff and MSF say - by Zoha's boss, the manager of the hospital.

Dr Zachariyah al-Ko'aity's role had been temporarily suspended while MSF oversaw the running of al-Amal, and now he was alleging that relief agency staff were stealing hospital equipment. He had earlier shared a video on Facebook of supplies being carried out of the hospital and loaded into lorries. MSF told the BBC that it was returning equipment it had borrowed from another facility in Aden.

Al-Ko'aity told the BBC he had entered the hospital to check supplies, and when he was obstructed from doing this, armed security intervened to break up a clash between him and the hospital's own security. He denied that anyone was threatened or attacked.

Such events might seem extraordinary in a country desperate for assistance in the face of a pandemic. But the political vacuum created by Yemen's ongoing war, and a government in exile, has bred a culture of chaos and mistrust, with local officials vying for power.

The situation in Yemen is said to be the world's worst humanitarian crisis

What's more, domestic media networks effectively act as propaganda channels funded by the warring factions, so the public instead relies on social media for news, making it easier for false rumours to flourish.

On 25 July, MSF pulled out of al-Amal hospital, citing security concerns. It moved to another hospital in Aden but there, too, it said it faced problems with the management, and after six weeks withdrew its team from the city altogether. Thousands of people are believed to have died from Covid at home, too afraid to seek healthcare.

Yemen's minister of health declined to give an interview but told the BBC that his government's relationship with MSF was excellent, and that in a large number of governorates MSF fulfils its humanitarian mission.

Counting the dead

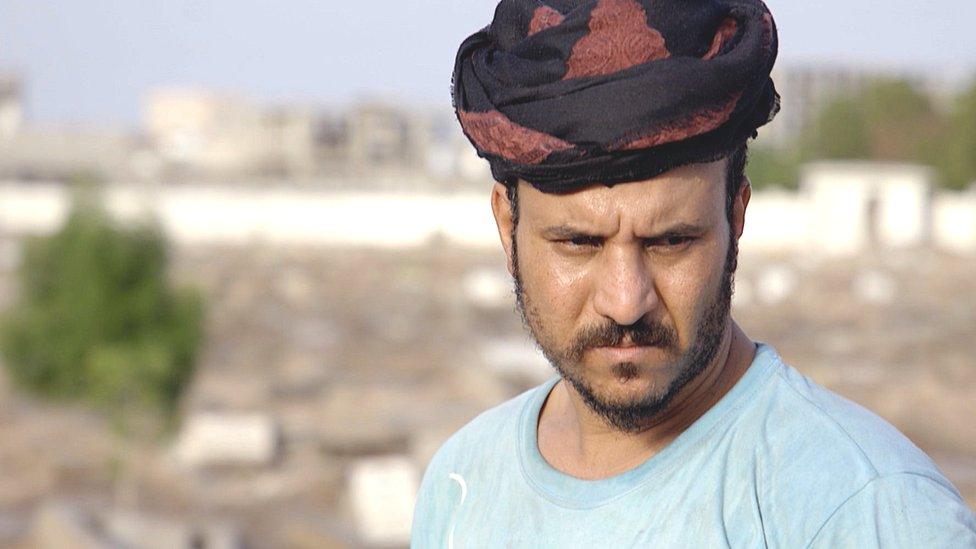

The toll the virus has taken on the city of Aden is stark at al-Radwan cemetery, the nearest functioning graveyard to al-Amal hospital, 10 miles (16km) away. Gravedigger Ghassan soon realised how serious the situation was when bodies arrived faster than he could bury them.

"I asked friends to help, but they also got sick. There were so many deaths, there wasn't even time to eat," he says.

Digging graves in al-Radwan cemetery

Covid death figures in Aden are hard to come by. There's been little-to-no testing, so it's difficult to establish how many of the people who have died during the pandemic suffered from Covid. But Ghassan has been keeping his own records.

The family of the deceased would provide him with a certificate stating cause of death. He noted down the name of every person he buried who had died in al-Amal hospital with Covid-like symptoms. He told me that in May alone - the pandemic's peak in the city - he buried more than 1,500 people. The death rate in the city was six times higher in May when compared with the previous year, according to official death records.

"It was unbelievable," Ghassan told me. "This was the first time I saw such a thing. It was worse than the war."

Ghassan kept note of who he was burying and their cause of death

For now, the Covid situation is relatively stable in Aden, Zoha says. She is working with a different medical facility run by the International Committee for the Red Cross and says very few are testing positive there for the virus at the moment.

"People here think the virus has disappeared, but scientists say that's not true."

Like many countries, Yemen is expected to suffer a second wave.

"We will be as unprepared as we were in the first one. They [the government] have learnt nothing."