Kuwait's stateless man who set himself alight

- Published

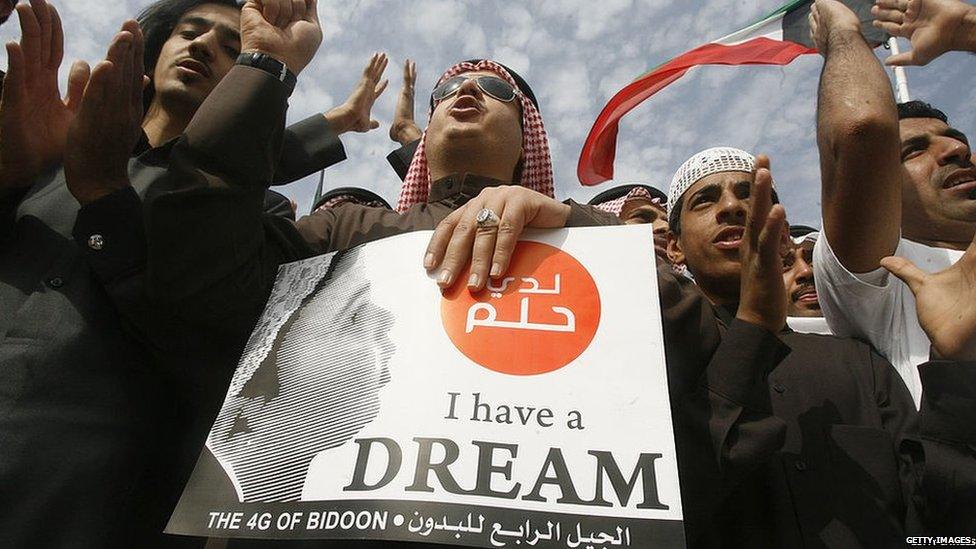

The Bidun have been stateless since Kuwait gained independence in 1961

When 27-year-old Hamad set himself on fire in Kuwait in December, it sent shockwaves across the country.

The tiny, oil-rich Gulf state seems an unlikely setting for the kind of desperate circumstances that would push someone to carry out such an extreme act. But Hamad is a member of Kuwait's stateless Bidun.

Bidun is Arabic for "without" - without nationality, which for members of the community means facing restricted access to wider society; without status, meaning tougher paths to education, medical care and employment. And - tragically for Hamad and his family - without hope.

'Everything had closed in'

Seventeen kilometres (11 miles) outside Kuwait City, Sulaibiya is a world away from the upscale shopping centres and high-rise glass buildings of the capital.

Omar lives there with his parents, his 10 siblings and their families, in a modest five-bedroom house in a run-down housing project where many of the Bidun population have settled.

The 33-year-old is close to his youngest sibling, Hamad.

"He's the kindest person on the face of the Earth, he's quite naive, always smiling," Omar says.

But about a year ago the young man became withdrawn, shutting himself away in his room and refusing his brothers' attempts to take him out of the house.

Omar felt his pain: "Everything had closed in on him."

The Bidun issue in Kuwait dates back to 1961, when some of the families living within its borders did not apply for citizenship following the country's independence from Britain.

Other Gulf Arab states such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE also have stateless residents, who are largely descendants of nomadic tribes who were living in the area but failed to apply for citizenship when the modern state was formed.

Elsewhere in the region others are stateless after the government stripped them of their nationality, such as in Bahrain where a number of dissidents considered a security threat have had their citizenship revoked.

The issue remains a complex one for the Kuwaiti government, which classifies the Biduns as "illegal residents".

It says that only 34,000 of the more than 100,000 stateless people in the country are eligible to apply for nationality and that the rest are natives of other countries or their descendants.

Daily struggle

After Hamad finished primary school, he was unable to register at a public high school due to his Bidun status. His family lacked the means to have him privately educated.

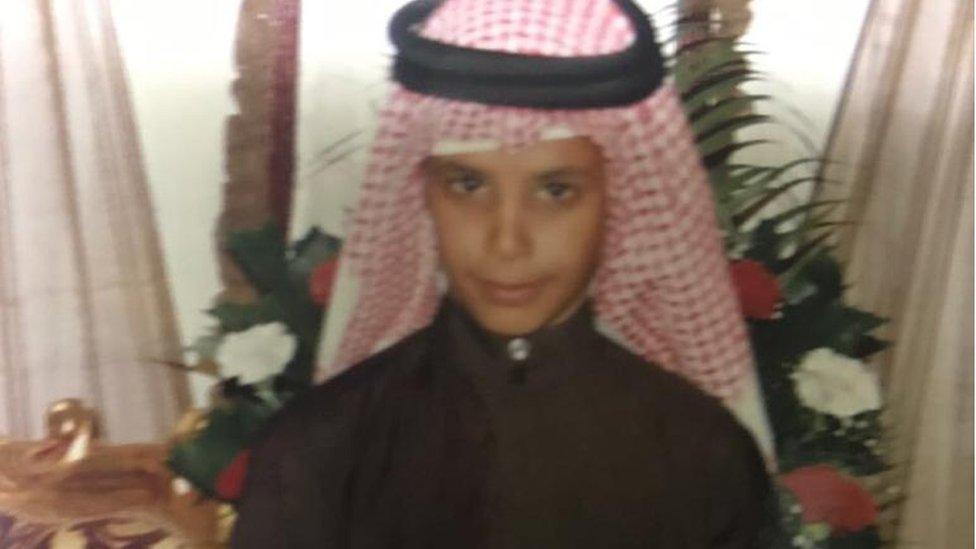

Hamad’s Bidun status meant that he left education at a young age

The boy grew up watching his father and brothers earn a precarious living buying and selling cars; they would sell a car one month and struggle for another four.

He seemed to decide that was not the life he wanted. His brother says that his dream was to join the military.

But faced with limited opportunities, Hamad did what he could to get by, at first selling watermelon on the street until the local municipality caught him.

He then tried breeding pigeons that he would buy for half a Kuwaiti dinar ($1.65; £1.21) but quit when he found himself selling them at a loss.

Kuwait classes Bidun as illegal residents

After Hamad completed an eight-month prison sentence for stealing sheep to sell, another brother, Jasem, managed to get him a travel document and took him on a trip to Morocco.

Omar says the holiday offered his brother a glimpse of another life.

"He saw the world, he saw life, he was happy. He was there for three weeks but it was as if he'd spent three years there. He spent the next five years talking about his trip to Morocco."

Spate of suicides

Recently, Hamad began telling his mother that he wanted to build a life, to get married and settle down. But with the family's finances already strained, she had little support to offer other than to remind him that "God will provide".

Omar said he had talked about taking his own life but that the family had not expected him to act on his words until one morning, in a fit of despair, he set himself alight.

Following the incident, MP Marzouq al-Khalifah called on the government to form a committee to look into the causes of a spate of suicides among members of the Bidun community.

"We live in a country of blessings... and yet we have people killing themselves because of difficult living circumstances and restrictions on their everyday lives."

MP al-Khalifah called on the government to look into suicides in the Bidun community

Bidun activist Abdullah al-Rabah says he would like to see the 34,000 Biduns identified as eligible be given citizenship and for the remaining to be granted civil rights, which would enable them to live their lives.

The 35-year-old adds that he and others like him feel a sense of loyalty to the country they were born in but that he understands the frustration of his community's youths.

"This is the third generation without a solution to the issue, how long are they going to wait? Of course it affects them."

For Omar, all he wants now is to be by his brother's side.

Normally, he would head out of Sulaibiya at every opportunity, to forget his worries and spend time by the sea alone. But now every day, he visits the hospital to look in on Hamad through the window of his room in the intensive care unit.

And he waits, hoping for the doctors to bring him good news.

All names in this report have been changed to protect individuals' identities.

You may also be interested in:

BBC News Arabic’s undercover investigation exposed the buying and selling of domestic workers in the Gulf

Related topics

- Published5 June 2015

- Published10 November 2014

- Published20 March 2013

- Published19 July 2011