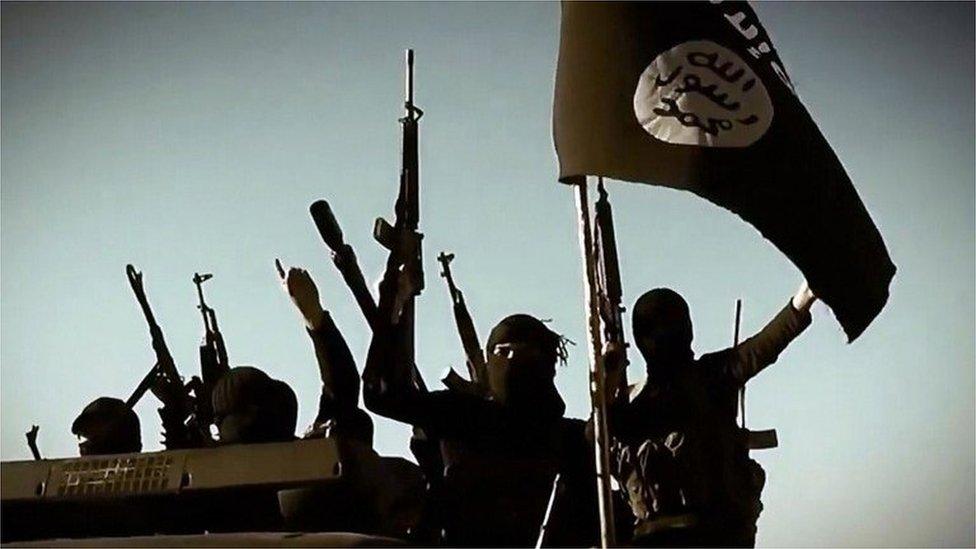

Islamic State tries to shore up relevance with Iraq carnage

- Published

The bombing in Baghdad was the deadliest suicide attack in the city for three years

The Islamic State group (IS) has not gone away. The twin suicide bombing in Baghdad on Thursday was a hideous reminder that the group which once controlled a vast swathe of territory across Syria and Iraq is still capable of mounting high casualty attacks in the heart of a city.

In this case its target was the Shia community, whom Sunni jihadists refer to dismissively as rafidain - rejectionists.

"Suicide bombings in major cities have always been a major part of IS strategy of creating sectarian tension and provoking retribution against Sunni populations," says Peter Neumann, professor of security studies at King's College London.

"IS needs sectarian conflict, in which it can portray itself as a provider of order," he adds.

'Show of force'

The market square that was hit was a target of convenience, the primary aim of the planners being to try to show they are still a force to be reckoned with after the loss of their physical territory in 2019.

The two suicide bombers targeted a busy second-hand clothes market

The attackers took advantage of the inherent good nature of Iraqis who crowded round to help a man who said he was unwell.

He waited until enough people had gathered and then triggered his bomb. A secondary explosion then killed others still on the scene during the aftermath, a tactic similar to one used by the IRA to kill 18 British paratroopers at Warrenpoint in Northern Ireland in 1979.

The Baghdad bombing was "a show of force signalling to supporters and adversaries that IS still exists and has the capacity to launch major attacks", says Prof Neumann.

Guerrilla tactics

But the reality is that IS today, while still dangerous, is a pale shadow of the force it was when it controlled an area of land roughly the size of Belgium.

For nearly five years, when it governed its self-declared "caliphate", it controlled the region's economy, extorting money from businesses, harvesting crops, pumping oil and selling it on the black market. Most importantly, it was able to lure thousands of recruits from the Middle East, Europe and Asia to join its cause.

That all ended with its military defeat by the US-led coalition at Baghuz in Syria. But an estimated 10,000 IS members remain at large in Syria and Iraq, external, mostly hiding in the population and with easy access to weapons and ready to exploit any grievances or grudges held by local Sunni communities.

Despite its territorial defeat, IS is still present in the Middle East and Africa

So complete was the destruction of the IS physical caliphate that it is unlikely to re-emerge in a similar form, wary of presenting itself as a target. Instead, in the Middle East, the group has gone back to doing what its predecessor, the Islamic State in Iraq group, did with maximum effect: carrying out high-impact hit-and-run insurgent attacks, intimidating local populations and trying to disrupt any semblance of normal life.

African battleground

Beyond its core area of Syria and Iraq, IS affiliates have fared better than the centre over the past two years.

In Afghanistan, IS has claimed to be behind some of the worst of the recent attacks. And as many analysts are now pointing out, Africa looks set to become the major battleground for jihad in this decade.

There, IS is in direct competition with groups affiliated to its rival, al-Qaeda, with both groups exploiting poor governance, corruption and porous borders in regions like the Sahel. Almost unthinkable a few years ago, IS now has a sizable foothold in Mozambique's gas-rich northern province of Cabo Delgado, while to the north, the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Shabab group controls much of the rural economy in Somalia.

Both groups - al-Qaeda and IS - have seen their operations curtailed since 2020 by the restrictions imposed globally by the coronavirus pandemic. People are no longer gathering in close proximity in crowded places in the way they were, while travel is heavily restricted.

But their desire to mount attacks, including in the West, is undiminished and they still have a pool of recruits willing to carry them out.

Related topics

- Published3 December 2020

- Published22 January 2021

- Published21 January 2021

- Published30 December 2020

- Published29 June 2020

- Published23 March 2019