Kuwait: Murder spurs demands for greater safety for women

- Published

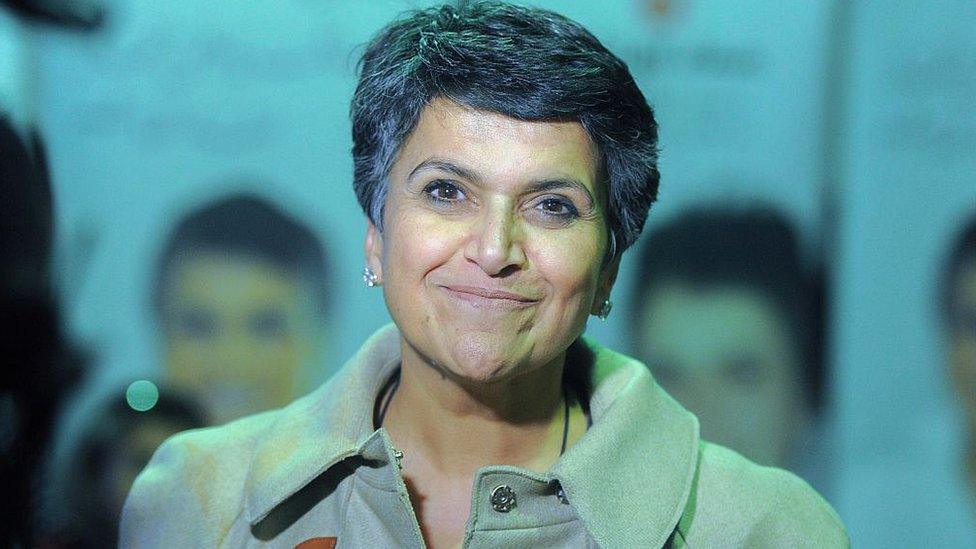

Rights groups in Kuwait have been campaigning for years for better protection for women

"We told you he'd kill her and he killed my sister!.. Where is the government?" Dana Akbar yells in grief after hearing the news.

It was a moment captured on video, external that unleashed a wave of outrage across Kuwait.

Farah Hamza Akbar was murdered in Kuwait last week despite earlier pleas from her family to the authorities to protect her from her harasser.

He reportedly abducted her in front of her daughter and niece.

Dana tweeted a picture of her sister, saying "We will not be silenced"

A statement from the interior ministry reported that a man had seized Farah Akbar from her car and taken her to an unknown location before leaving her outside the hospital where she was pronounced dead. He was arrested shortly afterwards and confessed to stabbing her in the chest, the ministry said.

He has been charged with first degree murder, which in Kuwait is punishable by death.

Farah's family told local media that the man was not known to them but that they had previously reported him for harassment.

Long road ahead

The incident has amplified already growing calls for greater protection for women from violence and harassment in Kuwait. Earlier this year, the social media campaign #Lan_ Asket (I will not be silent) was launched to spotlight the issue of harassment, prompting countless incidents from women.

Reports in recent years of a number of women killed at the hands of family members have also underlined the need for legislation and social change in order for women to feel safe.

A domestic violence law passed last September is seen as a positive step. It includes plans to set up shelters for women and allows for restraining orders to prevent abusers from contacting victims. But there are many reminders of the long road ahead.

No female candidates won seats in the last election, including the sole female incumbent MP

Following the murder of Farah Akbar, women and men gathered to express their condemnation at Irada Square, close to the sweeping white building of the National Assembly where an all-male parliament was elected in December last year.

It was also where Fatima al-Ajami had worked as a guard before she was allegedly murdered by her brother that same month.

Few details emerged of the background to the young woman's murder, as is often the case when it comes to women being killed by family members. But men who kill a female relative for alleged adultery may receive lenient sentences due to an article in the country's penal code that remains in place despite years of campaigning by activists to have it abolished.

Unheard voices

Voices who have until recently been under-represented in the dialogue on women's rights have also begun to emerge in the virtual space, emboldened by the anonymity that social media affords them.

Kuwaiti Feminists is run by a group of women from the country's largely conservative Bedouin tribal majority. The group's members choose to remain anonymous and agreed to speak to the BBC via private messages.

Activists say complaints by women of harassment and violence are often not taken seriously

They began meeting online last year and say that they have grown into a group of intersectional feminists who are concerned with all women living in Kuwait, including those from more vulnerable groups such as the stateless Bidun, foreign domestic workers and transsexual women.

When it comes to better protection from harassment and violence, the group agrees on the need for laws to better protect women. They say that all Kuwaiti women face difficulties in reporting threats and in their cases being taken seriously.

But they add that tribal women are less likely to find support and that their complaints may be dealt with by the authorities as family matters.

"The Bedouin Kuwaiti woman's problem begins inside the family because the tribe is a state within a state," said a member of the group. "The Bedouin woman obeys this state whose laws are enacted by her family and her whole environment."

Added obstacles

Activist Hadeel al-Shammari, who is a member of Kuwait's more than 100,000 stateless Bidun residents, explains that women like her often face added obstacles in seeking help. Members of the Bidun who do not have official identity documents are unable to report abuse or harassment to the authorities.

Many also struggle to access education or legal employment, leaving women with limited means to support themselves if they wish to leave an abusive situation, says Hadeel.

"We share in the suffering of women... but the Bidun woman also suffers from being in a weak position."

Lawyer and activist Omneya Ashraf says that although she has not experienced personal threats, she sees through her work the dangers faced by women in her society.

"Just because me, my female friends and family are living in safety, that doesn't mean that all women are safe. Farah's case began with harassment and ended in murder. So a woman is not safe."

- Published7 December 2020

- Published9 March 2020

- Published30 July 2020

- Published17 February 2021

- Published22 June 2018

- Published12 April 2019

- Published28 December 2020