Yemen: The children of a forgotten war

- Published

Bader lost part of his right leg after being hit by a shell on his way home from school

If suffering had an address, it might be al-Rasheed Street, in Taiz, a Yemeni city ringed by mountains and rebel Houthi fighters. On this narrow street of rough-hewn homes, the young can't escape a grinding conflict the world tends to forget.

A slight boy with a mop of dark hair leads us down the street, nimbly side-stepping potholes - with his crutches. Bader al-Harbi is seven years old, just a little younger than Yemen's war. His right leg has been amputated above the knee. The slogan on his T-shirt reads "Sport".

In the back yard of his family home, Bader sits on some breeze blocks, his stump exposed. His remaining foot has no shoe. His big brother Hashim is by his side, sharing his trauma and his silence.

Hashim's right foot has been mangled and he is missing a thumb. He fidgets endlessly with his hands as if trying to rub out the scars.

The boys were hit by Houthi shelling on an October morning last year as they came home from school on a break, according to their father, al-Harbi Nasser al-Majnahi. They have not been back to their classes since.

"Everything changed completely," he says, sitting cross-legged on a mattress. "They no longer play outside with other kids. They are disabled. They are scared and have psychological problems."

In a small voice, sounding younger than his nine years, Hashim says he would like to go back to school.

"I want to study and learn," he tells me. I asked Bader if he wants to go too. "Yes," he replies. "But my leg has been cut off, so how can I go?"

Their father says they have not been enrolled for the upcoming school year because he has no money for transport. And he has no way to get his family out of harm's way.

"Even though we are scared, we can't afford to live anywhere else," he tells me, "because the rent would be higher. So, we are forced to stay here, whether we live or die."

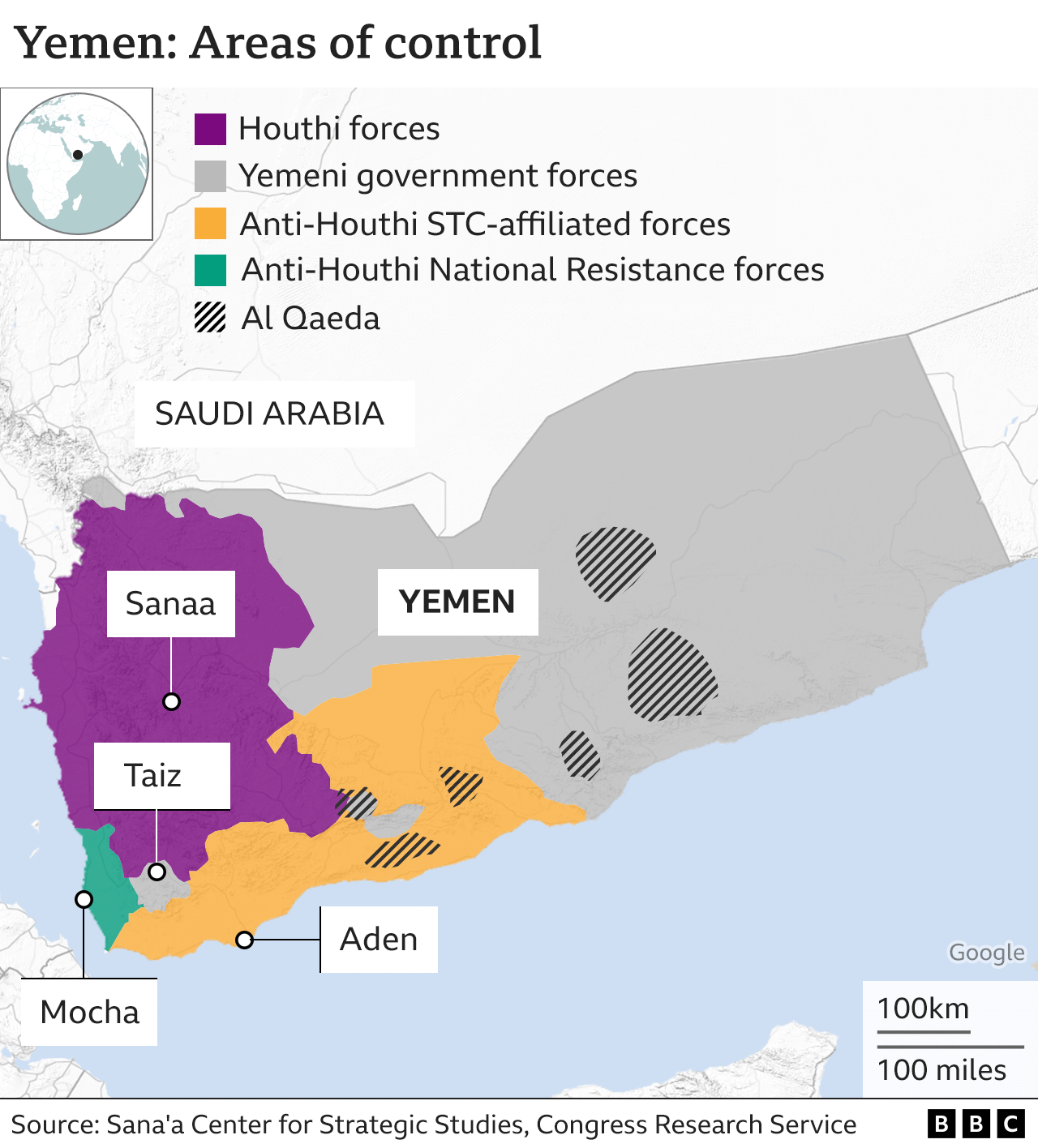

What began as a civil war has been fuelled by regional rivals backing opposing sides. Sunni Saudi Arabia supports Yemen's internationally-recognised government, weak as it is. Shia Iran backs the Houthi movement, formally known as Ansar Allah (or Supporters of God).

Nine years after the conflict began, Taiz bears the scars

In September 2014, the Houthis seized Yemen's capital, Sanaa, driving out the government. The following spring a Saudi-led coalition intervened, backed by the UK and the US.

The Saudis promised a quick operation to restore the government to power. Not quite.

Eight years, and thousands of coalition air strikes later, the Houthis still hold the capital. The Saudis now want a quick exit - militarily at least.

And on the front lines in Taiz, Bader and Hashim still sleep and wake to the sound of warfare.

"I hear explosions," says Bader, "and there are snipers. They shoot everything in the neighbourhood. I feel like there could be an explosion near me, or the house could be blown up."

We walk a few steps to the house next door - where another childhood has been ripped asunder.

Amir appears on the doorstep - a three-year old in a yellow T-shirt, silent and sombre. In place of his right leg there is a metal prosthetic. His father, Sharif al-Amri, helps him to stand, bending often to kiss his forehead.

Amir "remembers every moment" after the shelling that took his leg, his father says

Amir was maimed on the same day as Bader and Hashim - just a few hours later.

He was in a relative's house across the road when it was shelled, killing both his uncle and his six-year-old cousin. Amir survived but has penetrating wounds of memory.

As Sharif puts his son's pain into words, Amir nods off in the stifling heat, cradled in his arms.

"He remembers every moment after the shelling happened until he arrived at hospital. He says, 'This happened to my uncle, and this happened to my cousin.' He talks about the smoke and the blood that he saw. When he sees children playing, he gets very upset and says, 'I don't have a leg.'"

Every house on this street has its measure of fear. Munir's has more than most. The father of four leads me down an alleyway to his family home, which is right in the line of fire. Houthi gunmen are as near as his neighbours - he says about 20-30m away.

"There's a sniper is front of us," says Munir, crouching down by his living room window. "I can see him now if I open the window. If you go outside to the garden, he will shoot.

"We live in fear here in Taiz. People don't know when they will be hit by a missile or a sniper. God willing there will be peace and Yemen will go back to being great."

In the hallway we meet his eldest son Mohammed, an animated 14-year-old who relies on a wheelchair. When his school was shelled the other pupils ran away, leaving him behind. Now he worries that, if his house is hit, his family could be hurt trying to rescue him.

For more than 3,000 days Taiz has been virtually besieged, a battleground between government and Houthi forces. And the young have not been spared.

A local doctor told us that since 2015, he has treated about 100 child amputees - maimed by Houthi shelling, mines and unexploded ordnance.

Most of children maimed and killed in Taiz over the years have been victims of the Houthis. Others died in airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition - in the early war years - and some were killed by government forces. All sides have blood on their hands.

Yemen's conflict is now on a lower flame - since a UN-brokered truce last year that held for six months. It's no longer all-out war, but it's not peace either.

Saudi Arabia and Iran have shaken hands and made up. So far, so good. There have been talks between the Saudis and the Houthis, but sources tell us they have stalled. And there are no talks involving Yemen's own warring factions.

The country is increasingly fragmented, like a broken jigsaw that can't be reassembled. A separatist movement - backed by the United Arab Emirates - wants the south to be independent, as it was from 1967 until 1990. That is one more fissure in a fraying state.

I've been coming to Yemen since the war escalated in March 2015. This is my seventh visit. While the international community talks of peace moves, on the ground there is weariness and despair.

During three weeks on the ground in the south, many conversations felt like a farewell, a requiem to the nation.

Many doubt that Yemen will survive in its current form. Many more doubt that the Houthis will make peace.

"They claim they have a divine right to rule," said a twenty-something professional in Taiz, who preferred not to be named. "They claim the Prophet is their grandfather. I can't see them giving up their guns and going back to democracy and elections."

Or put another way by Gamal Mahmoud Al Masrahi, who is in charge of camps for the displaced in south-west Yemen, "the international community is living an illusion" when it thinks the Houthis will make peace.

We wanted to take the temperature in the Houthi-controlled north, home to most of Yemen's population of 32 million. But after we arrived in the country, the Houthis revoked our permission. Human rights campaigners in Sanaa say the de facto rulers are increasingly repressive.

As we leave al-Rasheed Street, Bader has come outside, but he's sitting alone by the side of road. Amir is being wheeled along on the crossbar of a bicycle by his father. "Don't be scared, my love," Sharif says, "I am beside you."

He asks his son what he wants in the future.

"Buy me a gun," Amir replies haltingly, his words jarring with his babyish voice.

"I will load a bullet in my gun and fire at those who took my leg."

Hunger also threatens Yemen's children

It was a three-hour journey on the back of a motorbike, across rough terrain - part road, part stones - in relentless heat. But this was the only way for Rajah Mohammed to get his desperately ill son, Awam, to a specialist children's hospital in Taiz.

First, he had to spend 10 days earning the money to pay for the trip from their home in the Red Sea port of Mocha. The journey cost 20,000 Yemeni rials, the equivalent of $14 (£10.73).

When Awam arrived at the Yemeni Swedish hospital - still so-called, though its Swedish benefactors are long gone - staff rushed to weigh and measure him. But the charts and scales were not needed to confirm he was severely malnourished. His wizened arms and painfully distended stomach told the story.

Rajah - who has four more children - has been battling to save his son for a year.

Rajah Mohammed travelled three hours by motorbike to take his son to hospital

"He always has a fever," he tells me, standing at Awam's bedside, fanning him with a piece of cardboard.

"We have been to all the hospitals in Mocha. We were told to bring him here. I can barely afford to feed my children. Sometimes all we have is bread and tea. It can be like that for a month or more."

Hunger is part of the bedrock of Yemen, but it has been compounded by the conflict which has destroyed livelihoods, driven up prices, displaced more than four million people and closed half the health facilities in the country.

Rajah is one of those made homeless by the war. "We have been displaced six or seven times," he says. "Every time we must move to a new place because we are scared of landmines."

Hunger has been stalking his child - and many others here - from birth. Nearly 500,000 Yemeni children under the age of five suffer from severe acute malnutrition and are struggling to survive, according to the United Nations (UN).

For Awam, there is one more threat. Tests show he may have leukaemia and could require lengthy treatment.

For Rajah, keeping one son in hospital means risking his other children going hungry at home. He takes Awam back to Mocha the following day. He tells doctors he will try to earn more money to bring him back.

Doctors say they are receiving many patients from the city - once famed for its coffee trade, now flooded with displaced families.

We travel there along the same bumpy road that Rajah took with his son, but in the comfort of a four-wheel-drive car.

We arrive at a rural health clinic, teeming with mothers clad head-to-toe in black abayas and face veils, holding up sick children. The air is heavy with the mothers' pleas and the babies' cries.

The three-room clinic is mostly closed these days but local officials decide to open it because we were in the area. The mothers surge forward, thinking we are foreign doctors, begging us to help their children.

A local doctor appears but he tells us staff at the clinic are on strike and will not be treating any cases. "We cannot do anything for them," says Dr Ali bin ali Doberah.

"We have not been paid for four months. Some of us are going to look for jobs that pay because we cannot feed our children."

The clinic is no longer getting support from foreign aid agencies who used to pay some of the salaries. Nine health centres have closed in Mocha and other areas of Yemen's west coast, because of lack of funding.

Across the country, aid agencies are scaling back. The UN World Food Programme has already made deep cuts, north and south. It says it will have to stop food supplies for between three and five million people by mid-September unless more money comes in.

As foreign donors hesitate, Yemeni children fight for life.

Umm Ahmed carries her daughter Safaa

In the middle of the throng there is an 11-month-old called Safaa - whose arms and legs are just skin and bone and whose face is contorted in pain. This fisherman's daughter is wasting away. She also suffers from a liver complaint.

"Sometimes she does not have food while her dad is at sea. We must wait for him to come back so we can buy her food," says her mother, Umm Ahmed.

"I am worried about her. I want to get help for her, but our circumstances are difficult."

Umm Ahmed's head is bent low, her shoulder slumped. Her family history is like a summary of Yemen's war years, written in blood and suffering.

She tells us she has been displaced for seven years, her brother-in-law was killed in an air strike, and her niece was blown up by a landmine. She has buried four of her nine children, because of malnutrition and liver problems. Now hunger is menacing her baby girl.

Umm Ahmed leads us the short distance to her home, which - like her country - has seen better days. The bright blue paint is fading from the walls. There is an ornate wooden door but little furniture and no toys. She puts Safaa in a hammock made from a shawl, swinging her back and forth to keep her cool.

Her husband, Anwar Taleb, looks worried and weary. He's a third-generation fisherman with a bushy beard, who can barely feed his family.

Safaa's parents cannot afford the five-hour journey to the hospital offering specialist treatment

"I go to sea for 15-20 days at a time and get what I can get," he says, "but for the past three months I have not found any work. Sometimes the money we make only covers the cost of the trip."

He tells us he has married off his two daughters - aged 14 and 15 - because he can't afford to feed them. We ask to meet them, but he says that even if he agrees, their husbands will not. Two more childhoods cut short. Two more hidden victims of war.

Now Safaa may be running out of time.

We give her parents a lift to a better-equipped local clinic - this one is functioning. She is admitted immediately, but doctors say she will need specialist treatment in the southern port city of Aden - a journey of about five hours that her parents cannot afford.

After a few days we learn that she too has been taken back home, where there may be little to feed her.

War, hunger, and poverty are intertwined here. Yemen's children may escape one and fall victim to the others.

And they are at risk of international neglect. The horrors of Ukraine are closer to home for many Western nations than distant suffering in the Arabian Peninsula.

Now more than ever Yemenis fear they are easy to overlook.

Who will help the wounded boys of Taiz - Bader, Hashim and Amir - and the starving infants of Mocha - Awam and Safaa?

Additional reporting by Wietske Burema, Ahmed Baider and Goktay Koraltan

If you'd like more information on the background to this story, the BBC World Service programme The Explanation has been speaking to Nawal Al-Maghafi - a BBC correspondent who has been reporting on the Middle East since 2012.

She explained how the complex war began between government-backed forces and Houthi rebels, and how it led to Yemen's current humanitarian crisis.

Listen here: How Yemen has been engulfed by civil war