The lives upended by colonial rule in the Middle East

- Published

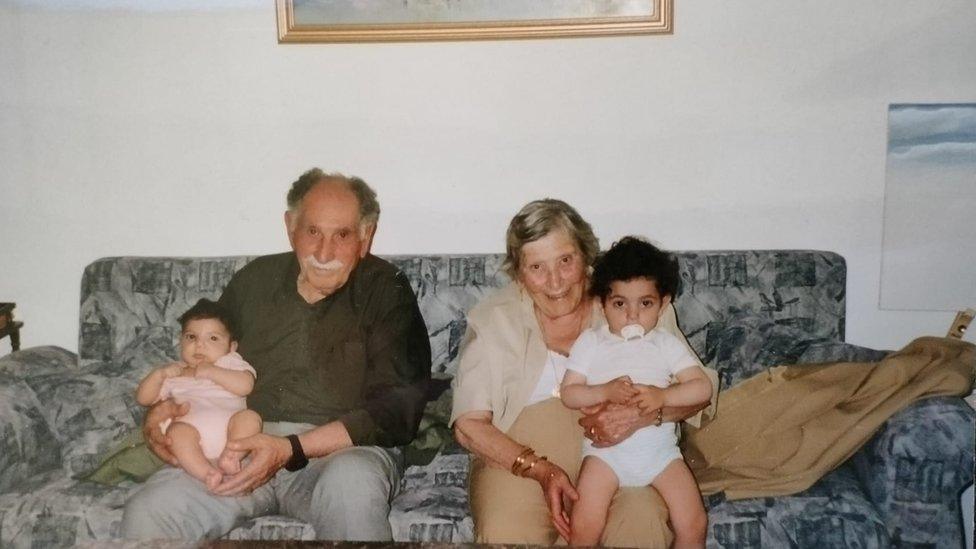

Eid Haddad's parents (pictured with their grandchildren) lived in a village subjected to collective punishment by British forces

Eid Haddad's parents were teenagers when they witnessed the full force of Britain's presence in Palestine in 1938.

"They saw the troops coming in and attacking people. My father told me that one of the men was hit on his head with a wooden hammer used to mince meat called [in Arabic] a modakah, and he died," says Mr Haddad.

"A man and his son were hanging tobacco leaves to dry them. They were just shot in the back."

"It was chaos," he says.

His parents lived in al-Bassa, a Palestinian village subjected to collective punishment by British forces, who called their actions at the time "punitive measures". These would target whole villages if troops faced attacks by armed rebels operating in the hills.

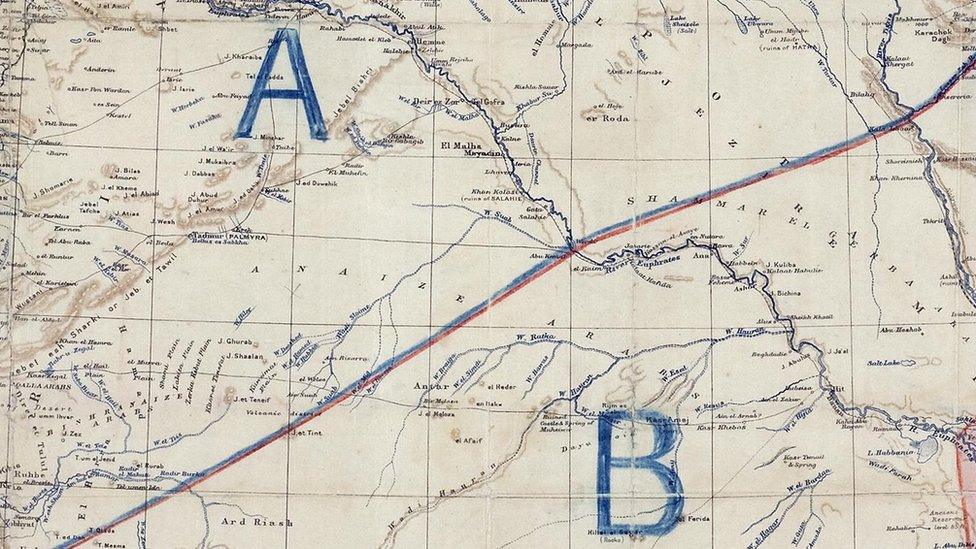

Mr Haddad gave the account of the atrocity for a new BBC Radio 4 series, The Mandates, starting on Tuesday at 1600BST, which examines how British and French control of the Middle East a century ago shaped the region in ways which still reverberate today.

In the series we hear from a range of historians; experts in the events a century ago on the territory covering modern-day Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. We spoke to women and men directly affected by the convulsions that gripped Europe and the Middle East, and their descendants today.

Eid Haddad shared his account of his childhood in Lebanon and the bloodshed his family endured

I first made contact with Mr Haddad last year when I was covering a Palestinian-led attempt to seek an apology for alleged war crimes carried out by the UK during its control of Palestine from 1917 to 1948.

As I spoke to him this time, during calls from his home in Denmark, he recounted the story of his own childhood in Lebanon amid the further bloodshed his family endured - by then dislocated from their homeland.

Like many other people I interviewed for the series, his parents' early lives unfolded as British and French rule sparked years of conflict and sectarian upheaval in the region.

His childhood encapsulated the bloody instability that gripped the Middle East in the decades after the European powers abandoned their interventions.

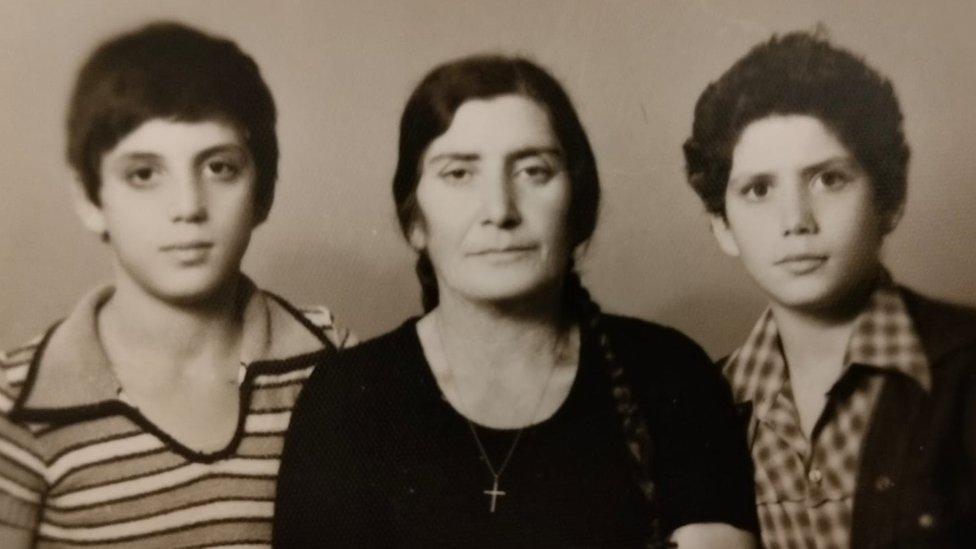

Eid Hadad (left) with his mother and his youngest brother in 1977

One historian we interviewed told us the history of the mandates is so foundational it is effectively "a history of the present".

During the First World War, as Britain invaded and captured the territory from the crumbling Ottoman Empire, it drew on growing forces of national self-determination. It made competing promises over swathes of the territory to Arabs, who sought independence across the region, and to the Zionist movement which sought a Jewish home in Palestine.

The British and French consolidated their control with so-called "mandates" to govern handed to them by the newly founded League of Nations - a body which was dominated by the two imperial powers.

In Palestine, Britain's policies ultimately set rival national movements on a collision course before it launched a brutal crackdown on an Arab uprising in the late 1930s. British forces would later face rebellion from Zionist militias, amid a series of chaotic policy reversals which saw the UK renege on immigration promises and turn back refugee boats of Holocaust survivors who had earlier escaped Nazi-occupied Europe.

"The British didn't know how to manage these things," the Israeli historian Tom Segev told me. "[They] treated Palestine as one would treat a lovable pet. It's nice to have, but it really shouldn't cause us too much trouble," he adds.

Meanwhile the French Mandate hived off Lebanon from Syria to create a strategic beachhead and imposed new boundaries over the whole territory in the early 1920s, before an Arab rebellion which they also ruthlessly suppressed. They split areas by ethnicity and religion in what historian James Barr told us was a "very straightforward and cynical" attempt to divide and rule.

In the years after the Second World War, Britain and France pulled out. In Palestine, London knew its withdrawal would turn an escalating territorial conflict into regional war, as the State of Israel was declared and Arab armies invaded.

Eid Haddad at his first communion at Dbayeh Camp. He was born in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon

Mr Haddad's parents fled al-Bassa as the village was destroyed by Jewish paramilitary forces. During the conflicts of 1947-8 at least 750,000 Palestinians fled or were forced from their homes in what Palestinians call the 'Nakba' or 'catastrophe'. Mr Haddad was born and grew up in a Palestinian refugee camp in neighbouring Lebanon.

The fragile sectarian climate between Christians and Muslims left in the wake of French rule of Lebanon was destabilised with the addition of Palestinian refugees. It was further aggravated during the rise of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), the armed group that launched attacks on Israel. The country also had powerful officials who still favoured regional pan-Arab alliance with Syria and Egypt - a movement which drew its roots back to rebellion against the mandates and earlier.

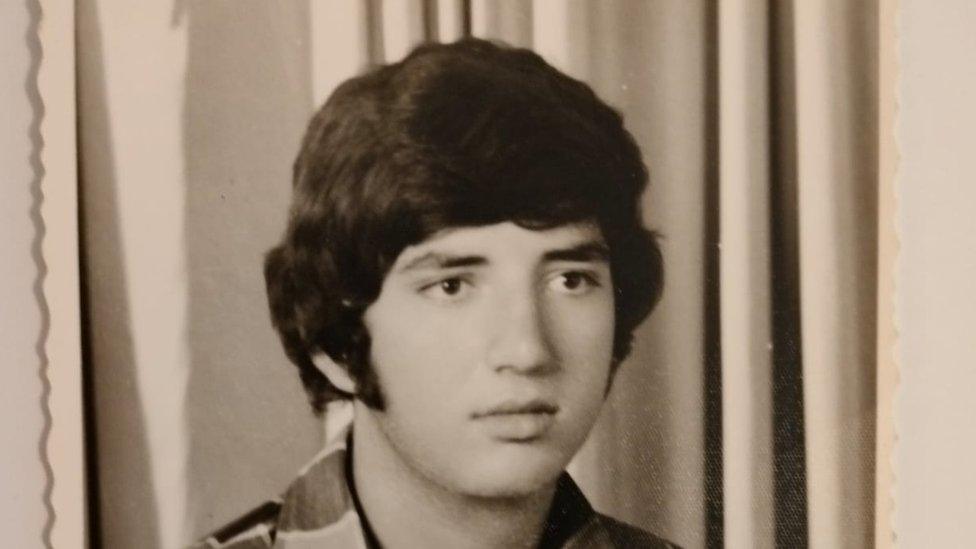

Lebanon later plunged into sectarian civil war. Mr Haddad, whose family are Palestinian Christians, describes how his 16-year-old brother was shot dead by Christian Lebanese ultranationalists - Phalangist militias - who targeted Palestinians and attacked his refugee camp north of Beirut in 1975.

The following year, he survived a mass killing, escaping gunmen by hiding in a wardrobe. He describes appalling and barbaric humiliation of survivors by the militias.

Rashid Haddad was shot dead when he was just 16 years old

Mr Haddad tells me he manages lifelong symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which he traces back to what he experienced as a child.

"My parents - I think they also suffered PTSD because they have seen also lots of things as children. And imagine my father, he was about to be taken by the British troops to be interrogated," he says, explaining that British forces separated women from men who were detained by troops during the atrocity in al-Bassa in 1938.

His father, then a teenage boy, was spirited towards the line of women, says Mr Haddad, by a villager who disguised him as a girl.

"So they just covered him, covered his head with a scarf and gave him a dress. And in this way, they saved him from being tortured," he says.

The UK government has never acknowledged the atrocity in al-Bassa which is believed to have killed more than 30 people.

From Europe, Mr Haddad describes how he has never been able to return home.

He says: "It feels like a big piece of myself is missing. I feel just like an island in an ocean which is totally foreign to me."

- Published7 October 2022

- Published16 May 2016

- Published2 November 2017