Could an Israeli ground invasion of Gaza meet its aims?

- Published

Israel's military has called up a record number of reservists for the war with Hamas

Israel's leaders have declared that Hamas will be wiped off the face of the Earth and Gaza will never go back to what it was.

"We have set two goals for the war: to eliminate Hamas by destroying its military and governing capabilities and to do everything possible to bring our hostages at home," announced Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, as Israel expanded its ground operations in Gaza.

Operation Swords of Iron began in response to the killing of more than 1,400 people by Hamas gunmen in a brutal attack on Israeli communities, and Israel's chief of staff has said the military are fighting "for our right and the right of future generations to live in safety".

That goal of ending Hamas rule has been endorsed by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Defence Minister Yoav Gallant said in October that the final phase of Israel's Gaza plan was for a "new security regime" there, with no Israeli responsibility for daily life. Mr Netanyahu has since said "Israel will, for an indefinite period have the overall security responsibility", to prevent further Hamas attacks.

Israel's aims appear far more ambitious than anything the military has planned in Gaza before. But are they realistic, and how can its commanders possibly fulfil them?

Entering the Gaza Strip involves house-to-house urban fighting and carries immense risks to a civilian population of more than two million. Officials in Hamas-run Gaza say 10,000 people have already been killed, and hundreds of thousands more have fled their homes.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) have the added task of rescuing 240 hostages, held in unknown locations across Gaza.

"I don't think Israel can dismantle every Hamas member, because it's an idea of extremist Islam," says military analyst Amir Bar Shalom of Israel's Army Radio. "But you can weaken it as much as you can so it has no operational capabilities."

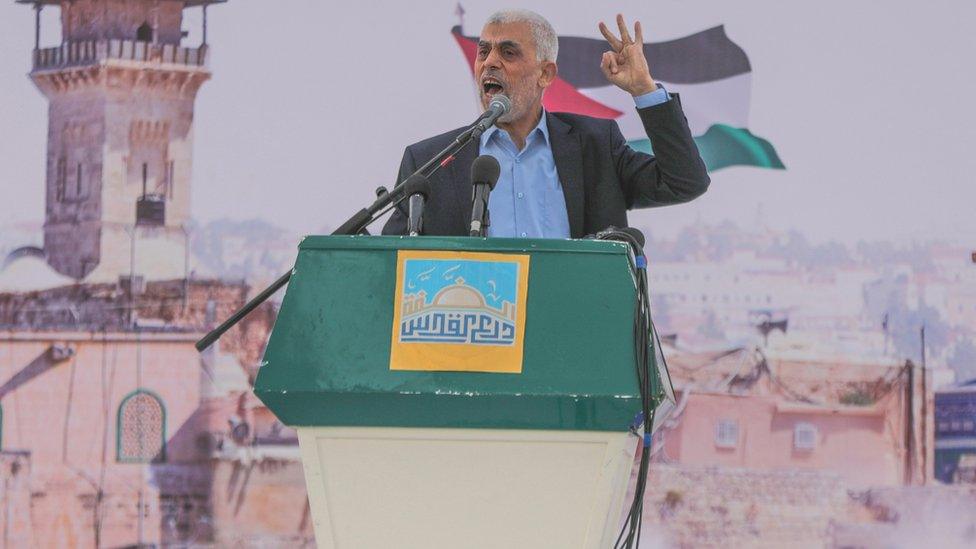

Yahya Sinwar, head of Hamas in Gaza, has been identified as a prime target by Israel

Weakening it so it no longer poses a military threat to Israelis might be a more realistic objective than dismantling it entirely. Israel has already fought four wars with Hamas, and every attempt to halt its rocket attacks has failed.

Michael Milstein, head of the Palestinian studies forum of Tel Aviv University, agrees destroying Hamas would be highly complicated. He says it would be pretentious to believe you could uproot the idea that embodies Hamas - an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood that has influenced Islamist movements around the world.

Quite apart from the 25,000-plus strength of Hamas's military wing, it has 80-90,000 more members who are part of its social welfare infrastructure, or Dawa, he says.

In Antony Blinken's words, Hamas's "perverted idea" has to be combated with a "better idea" and a vision that gives people something to hope for.

Ground invasion fraught with risk

The military operation is at the mercy of several factors that could derail it.

Hamas's armed wing, the Izzedine al-Qassam Brigades, has the use of an extensive network of tunnels and it has targeted Israeli forces with snipers and fighters armed with anti-tank missiles.

The civilian death toll has soared since ground operations expanded on 27 October, and the IDF has lost increasing numbers of soldiers in combat.

Israelis have been warned to prepare for a long war, and a record 360,000 reservists have reported for duty.

The question is how long Israel can continue its campaign as international pressure grows for a ceasefire, with supplies of water, power and fuel cut off, and UN warnings of an unfolding human catastrophe.

"The government and military feel they have the backing of the international community - at least Western leaders," says Yossi Melman, one of Israel's leading security and intelligence journalists.

But sooner or later he believes Israel's allies will step in.

"It's very complicated because it needs time and the US administration won't let you stay in Gaza for a year or two," says Michael Milstein.

Saving the hostages

Many of the hostages are Israelis, but there are also a large number of foreign citizens and dual nationals among them, meaning several other governments - including the US, France and the UK - have a stake in this operation and their safe release.

Heart-rending appeals from families of those in Hamas captivity are ramping up pressure on Israel's leaders, and Hamas's political leader in Gaza, Yahya Sinwar, has said they are ready to swap all the hostages for the thousands of Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails.

That kind of deal is unlikely.

In 2011, Israel exchanged more than 1,000 prisoners for the release of a soldier, Gilad Shalit, held by Hamas for five years. Yahya Sinwar was among those freed, and is now their top man in Gaza.

More on Israel-Gaza war

Follow live: Latest updates

Analysis: Jeremy Bowen's five new realities after four weeks of war

From Gaza: Stories of those killed in Gaza

History behind the story: The Israel-Palestinian conflict

Neighbours watching closely

What could also affect the duration and outcome of a ground offensive is how Israel's neighbours react.

Egypt's Rafah border crossing with Gaza has become a humanitarian focal point for supplies getting into Gaza. Hundreds of foreign passport holders and some of the wounded have been allowed to leave but more remain.

"The more Gazans suffer following the Israeli military campaign, the more pressure Egypt will face, to appear as if it has not turned its back on the Palestinians," says Ofir Winter of Israel's Institute for National Security Studies.

But that will not stretch to Cairo allowing a mass crossing of Gazans into northern Sinai. President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi has said Egypt rejects any attempt to move Gazans forcibly into the Sinai peninsula, adding that it would prompt Egyptians to "go out and protest in their millions".

An internal Israeli intelligence ministry policy paper has raised the prospect of the Gaza population being expelled from the territory, but only a handful of far-right politicians have shown interest in the idea.

Jordan's King Abdullah has talked of a "red line" for any possible attempt at pushing Palestinian refugees out of Gaza: "No refugees in Jordan, no refugees in Egypt," he warned.

Israeli air strikes and artillery have bombarded Gaza for days, since Hamas slaughtered Israeli civilians

Israel's northern border with Lebanon is also under close scrutiny. There have already been regular, deadly cross-border attacks involving Islamist militant group Hezbollah, and communities on both sides have been evacuated.

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah has said "all options are open", but for the moment there is no indication of a broader axis against Israel opening up from the north.

Hezbollah's main sponsor, Iran, has threatened "new fronts" against Israel, and Iran-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen have fired missiles and drones towards Israel too.

But US President Joe Biden has issued a stern warning to Iran and its allies: "To any country, any organisation, anyone thinking of taking advantage of this situation, I have one word: Don't!"

Two US aircraft carriers, the USS Gerald Ford and USS Eisenhower, have been sent to the eastern Mediterranean to emphasise that message, and some 2,000 US troops have been placed on alert to respond to unfolding events.

What is Israel's endgame for Gaza?

If Hamas were to be significantly weakened, the question is what would go in its place.

Israel pulled its army and thousands of settlers out of the Gaza Strip in 2005 and government officials have said repeatedly they have "no desire to occupy or reoccupy Gaza". US President Joe Biden has said any move to occupy it again "would be a big mistake".

A month into the war, Benjamin Netanyahu said once the war was over, it would be governed by "those who don't want to continue the way of Hamas", and that Israel would "for an indefinite period" have overall security responsibility. While not the same as re-occupation, it implies Israel would demand a substantial role.

Ofir Winter believes a shift in power could potentially pave the way for the gradual return of the Palestinian Authority (PA), kicked out from Gaza by Hamas in 2007.

The PA currently controls parts of the West Bank, but is weak there, and persuading it to return to Gaza would be highly complicated.

Antony Blinken has said it would make "most sense... for an effective and revitalised" PA to run Gaza, although a number of other countries in the region could take part in "temporary arrangements" that might involve international agencies.

What is clear is that a power vacuum would lead to even more problems.

The United Nations could theoretically fill the gap in running Gaza temporarily, as it did in Kosovo after Serbian forces withdrew in 1999. But that kind of solution would not go down well in Israel, where the UN is widely mistrusted.

Another option might be to create an administration, run by Gaza's mayors, tribes, clans and non-governmental organisations, with involvement from Egypt and the US, the PA and other Arab states, says Michael Milstein.

Egypt's president has himself shown no interest in controlling Gaza but has pointed out that if a "demilitarised Palestinian state had been created long ago in negotiations, there would not be a war now".

Gaza's devastated infrastructure will ultimately have to be rebuilt in the way it was after earlier wars.

Israel will want even tighter restrictions on "dual-use goods" entering Gaza that could have a military and civilian purpose. And there have been calls for an expanded buffer zone along the fence with Gaza to provide greater protection for Israeli communities.

Related topics

- Published13 October 2023

- Published11 October 2023