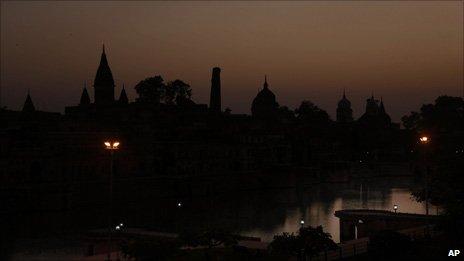

Ayodhya: Has India's flashpoint town moved on?

- Published

Ayodhya is an ancient pilgrim town

VN Arora is a teacher in the only college in India's northern pilgrim town of Ayodhya where Hindu fanatics tore down a mosque and triggered off nationwide religious riots nearly two decades ago.

He does not teach the scriptures or Hindu mythology in this ancient, temple-studded sacred town. Instead, Mr Arora lectures students on defence and strategic studies at Saket College, which has over 18,000 students on its rolls.

In 1992, when the 16th Century Babri mosque was destroyed, the college taught 14 subjects. Today, it offers 29, including diplomas in computer sciences, bio-technology and fashion design.

"I have over 2,000 students and nine teachers in my department. We teach warfare, geopolitics and international relations. All this is very popular with the students of Ayodhya," says Mr Arora, an avuncular and sprightly man of 59.

So has India's flashpoint town moved on? Has it begun to live down its infamy as a place which prised open the country's religious fault lines and triggered off some of the worst rioting since independence?

Moving on

On the surface, it appears so.

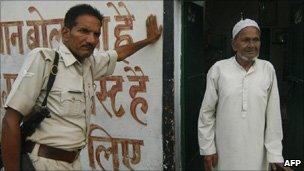

Ayodhya's residents live under the shadow of security

Student numbers at Mr Arora's college have trebled since December 1992, when the mosque was torn down. There are more than a dozen English tutorials in town. The place has a couple of hotels. Two sugar and a paper factories are chugging along.

"The young want to move on and move out. They want to swim with the mainstream. It is no longer 1992," Mr Arora says.

But not everybody is convinced by this argument. Bimalendu Mohan Pratap Mishra, a scion of Ayodhya's princely family, is one of them.

"Ayodhya was and remains a pilgrim town at heart. Change comes slowly to such places," he says, reclining on a shiny blue sofa in his whitewashed palace.

Mr Mishra is possibly right.

In the dank, serpentine lanes of this town of 40,000 mostly Hindu people and several thousand Hindu temples, faith hangs heavy.

Throngs of ochre-robed gurus and mendicants make their way through the town's bustling bazaar, selling risque films, devotional music and videos and kitschy religious bric-a-brac.

"We are going to college and migrating to big cities for work. But Lord Ram resides in our hearts always, he resides in every corner of Ayodhya," says Chetan Pandey, a student.

There is no evidence that the hero of the popular Indian epic Ramayana was a historical character.

But a mixture of faith, sentiment and myth have led many Hindus of Ayodhya - and elsewhere in India - to believe that Ram was born at the very site in Ayodhya where the Babri Mosque was built in the 16th Century.

"But there was no religious tension between Hindus and Muslims here till December 1949 when an official allowed an idol of child Ram [Ram Lalla] to be placed inside the mosque under the cover of darkness," says VN Arora, who was born in the city.

'Inventing a reality'

These moves, in the words of historian Mukul Kesavan, "invented the reality of Ram worship in a mosque" and ensured that a "medieval mosque continuously in use till the mid-1930s was prised open for Hindu worship".

So why did a sleepy pilgrim town and "birthplace of Ram" turn into a religious battleground?

Many locals believe infamy was foisted on Ayodhya by Hindu fanatics who "invaded" it to demolish the mosque on the back of a Hindu nationalist movement whipped up across India by a group of militant Hindu organisations associated with India's main opposition Bharatiya Janata Party.

More than a dozen Muslims were killed by mobs in the aftermath of the demolition in the town, and at least 260 Muslim shops and homes gutted.

The destruction of the mosque also led to riots across India, in which about 2,000 people were killed.

Locals say it was again the handiwork of fanatics from outside, though others say that some locals connived in the killings and pillage.

The transformation of a sleepy pilgrim town into a "Hindu Vatican", as many Hindu nationalists prefer to call it, has been a boon and bane for its residents.

The dispute has hit business in the town

The number of pilgrims and visitors to the town shot up after the demolition of the mosque, boosting the local economy.

At the same time, locals and shop owners suffer when security is tightened after intelligence pours in of an impending terror attack. The pilgrim traffic dries up and Ayodhya slips back into its tense, troubled state.

It has been happening now in the days leading to a judgement by the high court in Allahabad. The court will decide on Thursday who owns land where the mosque stood.

Even the students of Mr Arora's college are suffering: over the last fortnight, security forces have taken over the place, shutting out the students and teachers.

The demolition of the mosque earned Ayodhya a notoriety which locals say they want to bury by embracing the court judgement.

No Answer

The chain smoking 90-year-old Hashim Ansari, the oldest litigant involved in the court cases, insists that he will accept the court's ruling "gracefully" - even if it goes against Muslims.

Sitting in his poky home, the Ayodhya-born former tailor had been blowing hot and cold about the consequences of an adverse judgement against Muslims.

"If we win, we will not celebrate it. If the Hindus win, we will not take to the streets against the verdict," Mr Ansari says.

Mr Ansari is the oldest litigant in the land ownership case

Some distance away, in a narrow lane, the priest of the makeshift temple at the disputed site, Acharya Satindra Kumar Das, says people want a settlement to the dispute.

"Ayodhya is suffering because this impasse lingers on. It has given the place a sad image. But I see no compromise happening, because either the Hindus or the Muslims have to make a sacrifice. And that won't happen," he says.

Ayodhya will have to wait longer to bury its ghosts - Thursday's judgement is certain to be challenged by the losing side in the Supreme Court.

"Then will it continue in the courts for another 60 years?" asks Pradeep Prajapati, who sells bangles near the heavily secured site where the mosque once stood. "How long can we live with this apprehension?"

It is a question that all of India is asking, and nobody has an answer.

- Published23 September 2010

- Published17 September 2010