India's coalition woes: Where did it all go wrong?

- Published

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh reshuffled his cabinet on Wednesday, hoping it would restore confidence in his beleaguered government

Not very long ago, India's Prime Minister Manmohan Singh could do no wrong - or so it seemed.

Long considered a man of unimpeachable integrity, Mr Singh coasted to a second term as the prime minister of the world's second most populous nation in May last year.

From 145 seats in the lower house of parliament, Lok Sabha, in 2004, his Congress party increased its share of seats to 206 in the May 2009 polls.

By current Indian electoral standards, it was an impressive performance.

With the opposition in disarray, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government appeared to be on a roll.

An unshakeable understanding between Mr Singh and Congress President Sonia Gandhi ensured political stability in the country. Frequent meetings between the two suggested a neat division of responsibility between party and government.

'Mind-boggling'

In the past few months, the personal equation may have continued, but things have begun going horribly wrong for the Congress-led coalition.

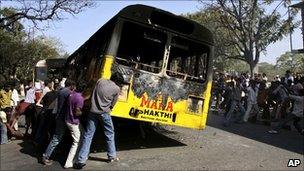

Regular protests by Telangana activists are just one of the government's worries at the moment

Inflation, corruption scandals, a massive and ongoing agitation for a separate state of Telangana in southern India, apparent favours in the allocation of land, the abuse of discretionary powers by state leaders: everything seemed to go wrong at the same time for Mr Singh and his government.

A spate of court cases has given the government a headache.

The Supreme Court made some sharp observations of official decisions in what has come to be known as the 2G scandal - where the government is said to have incurred losses of billions of dollars in the sale of mobile phone spectrum.

And on Wednesday, hearing a case of unaccounted money being held by Indians in foreign banks, the court criticised the coalition for its reluctance to provide more information.

"It is a pure and simple theft of national money," said Justices B Sudershan Reddy and S S Nijjar. "We are talking about mind-boggling crime. We are not on the niceties of treaties."

Such comments have become a near-daily affair for the government in one case or the other.

And so far it has not been able to come up with convincing answers.

Government 'rudderless'

In what the Indian media has dismissed as a lame effort to energise his government, Mr Singh changed the portfolios of as many as 36 ministers on Wednesday, terming it a "minor reshuffle" and promising a more "expansive exercise" in the next few months.

But analysts believe that this may not help the image of the government as a performing entity.

Neena Vyas, associate editor of The Hindu newspaper, told the BBC: "More important is whether the government is able to break the logjam with the opposition, which prevented parliament from conducting any business in the recent session of parliament."

Ms Vyas was referring to the impasse in parliament, in which all sections of an often-divided opposition came together to demand a parliamentary inquiry into the 2G scandal.

Several officials who chose to remain anonymous told this writer that a sense of paralysis had gripped the government.

"No-one wants to take decisions in such an environment where everything is suddenly under question. The government appears rudderless," one of them said.

"It's sad, but this is true," confirmed a junior minister in Mr Singh's government, who told me he believed the prime minister had been extremely hurt by the personal allegations levelled against him by some opposition leaders.

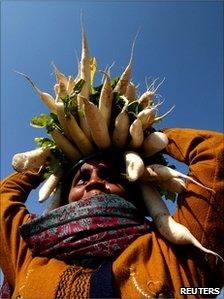

The government is also struggling with spiralling food and fuel prices

Challenges ahead

It is an open question whether the reshuffle carried out by Mr Singh will mean anything in real terms.

There also appear to be divergences on key issues like a new Food Security Bill between the government and the National Advisory Council, a powerful lobby group within the establishment headed by Mrs Gandhi.

Mrs Gandhi has said publicly there should be "no tolerance" for corruption or misconduct.

At a Congress party conference in December, she suggested fast-tracking corruption cases against public servants, providing full transparency in public procurements and contracts, and reviewing the discretionary powers of state chief ministers.

She also called for an open and competitive system of exploiting natural resources.

Analysts are comparing Mr Singh's second tenure to the political crisis, linked to a corruption scandal, that former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi faced back in the mid-1980s, despite having a huge majority in parliament.

Eventually, Mr Gandhi lost the 1989 elections and a motley coalition of parties took power.

While there are similarities between then and now, Mr Singh and Mrs Gandhi still have the opportunity to retrieve lost ground.

A lot will depend on whether or not the government can check spiralling food inflation. Also, whether the Congress and its allies are able to blunt the opposition attack during next month's budget session of parliament will be critical.

Mr Singh and his government still have a little over three years to go before the May 2014 elections.

But the prime minister, Mrs Gandhi and the government have a tough job ahead if they fancy a return to power in Delhi.

- Published13 January 2011

- Published7 January 2011