Deadly protest exposes cracks in Afghan strategy

- Published

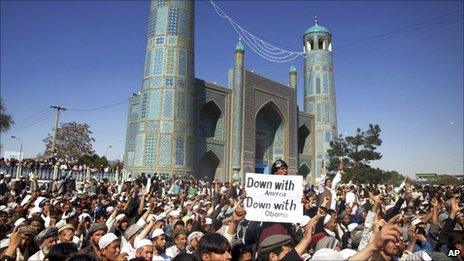

The protest began after Friday prayers in Mazar-e Sharif

After protesters in the normally peaceful Afghan city of Mazar-e Sharif turned their wrath on the UN, killing seven foreign staff, the BBC's Paul Wood in Kabul examines what might have been behind the attack and what it means for Nato's strategy.

No one saw this coming. Not the UN, not Nato, not the Afghan police.

Mazar-e Sharif was the last place in Afghanistan where such an attack might have been expected.

The city usually has a bustling air about it. The local economy is thriving. It is usually quiet and calm. You might even see the odd tourist wandering around the famous Blue Mosque.

Outside the Blue Mosque yesterday, an imam began to harangue the crowd. Hundreds of Korans had been burned in the US, he said, not just one.

He was referring to events at a church in Florida on 20 March, when Pastor Wayne Sapp set light to a copy of the Koran. He was supervised by Pastor Terry Jones, who last year aborted a plan to burn copies of the Koran on the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks.

Taliban "infiltrators"

At the main Friday prayers in Mazar-e Sharif, the worshippers had been told to demonstrate.

But then it was the street sermon, outside, which seemed to inflame them.

What happened next is a matter of dispute. The provincial governor insists that the (so-far) peaceful protesters had not even intended to march on the UN until Taliban "infiltrators" diverted the crowd.

For some Afghan - and international -- officials, this was a pre-planned attack, carried out by the Taliban, using the anti Koran-burning protest as cover.

Officials said the protest had been peaceful before the attack

If that is true, it shows how the insurgency retains the capability to strike even in places where it traditionally has very little support.

Despite some Pashtun-Tajik ethnic tensions in Mazar, the Taliban has never really had a foothold there.

The city was considered so safe, it was among the first seven locations named as ready to be handed over from Nato to Afghan security control in July.

The Afghan police could not protect the UN mission on Friday.

Questions will now, inevitably, be raised about security transition in Mazar-e Sharif, and perhaps elsewhere too.

The Taliban denies it was behind the attack there or the trouble in Kandahar on Saturday. These were "the pure acts of responsible Muslims," said a spokesman - foreigners burning Korans had brought down the wrath of ordinary Afghans upon their heads.

Latent hostility

This is a deeply conservative, deeply religious country. An insult to Islam will inflame passions as no other issue.

If the violence was spontaneous, that is perhaps more worrying for the international community than if there had been a Taliban guiding hand.

It would show how precarious is the position of the international community here; even how much latent hostility there is for the international presence in Afghanistan.

A statement by the Afghan police that some UN workers were beheaded may in fact not be correct. But at least one of the victim's throat may have been cut; others were stabbed, it seemed, rather than shot.

The UN is not, so far, evacuating its personnel. The US military, for its part, is worried not just about Afghanistan but about many other Muslim countries where it has troops.

That is why General Petraeus, who is in charge of US forces in Afghanistan, personally appealed to Pastor Terry Jones last year not to burn a pile of Korans, as he had been threatening to do.

When the Koran was burned in a Florida church two weeks ago, there was little immediate reaction.

But news is getting out and spreading now and the fury - in Afghanistan - seems to be building.

Even if the Taliban did not orchestrate the events in Mazar-e Sharif, it may be strengthened by them.

- Published20 January 2011

- Published1 April 2011

- Published11 September 2010