Where are India's millions of missing girls?

- Published

- comments

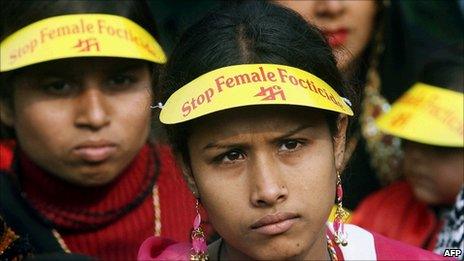

India's 2011 census shows a serious decline in the number of girls under the age of seven - activists fear eight million female foetuses may have been aborted in the past decade. The BBC's Geeta Pandey in Delhi explores what has led to this crisis.

Kulwant has three daughters aged 24, 23 and 20 and a son who is 16.

In the years between the birth of her third daughter and her son, Kulwant became pregnant three times.

Each time, she says, she was forced to abort the foetus by her family after ultrasound tests confirmed that they were girls.

"My mother-in-law taunted me for giving birth to girls. She said her son would divorce me if I didn't bear a son."

Kulwant still has vivid memories of the first abortion. "The baby was nearly five months old. She was beautiful. I miss her, and the others we killed," she says, breaking down, wiping away her tears.

Until her son was born, Kulwant's daily life consisted of beatings and abuse from her husband, mother-in-law and brother-in-law. Once, she says, they even attempted to set her on fire.

"They were angry. They didn't want girls in the family. They wanted boys so they could get fat dowries," she says.

India outlawed dowries in 1961, but the practice remains rampant and the value of dowries is constantly growing, affecting rich and poor alike.

Kulwant's husband died three years after the birth of their son. "It was the curse of the daughters we killed. That's why he died so young," she says.

Common attitude

Her neighbour Rekha is mother of a chubby three-year-old girl.

Last September, when she became pregnant again, her mother-in-law forced her to undergo an abortion after an ultrasound showed that she was pregnant with twin girls.

"I said there's no difference between girls and boys. But here they think differently. There's no happiness when a girl is born. They say the son will carry forward our lineage, but the daughter will get married and go off to another family."

Kulwant and Rekha live in Sagarpur, a lower middle-class area in south-west Delhi.

Here, narrow minds live in homes separated by narrow lanes.

The women's story is common and repeated in millions of homes across India, and it has been getting worse.

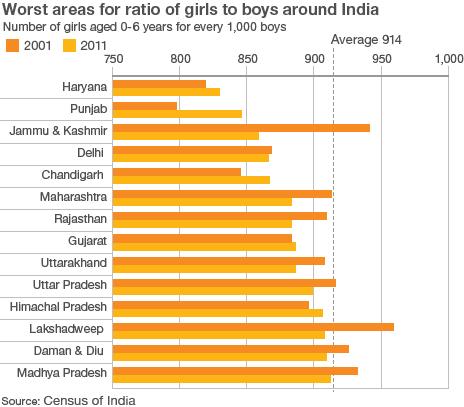

In 1961, for every 1,000 boys under the age of seven, there were 976 girls. Today, the figure has dropped to a dismal 914 girls.

Although the number of women overall is improving (due to factors such as life expectancy), India's ratio of young girls to boys is one of the worst in the world after China.

Many factors come into play to explain this: infanticide, abuse and neglect of girl children.

But campaigners say the decline is largely due to the increased availability of antenatal sex screening, and they talk of a genocide.

The government has been forced to admit that its strategy has failed to put an end to female foeticide.

'National shame'

"Whatever measures have been put in over the past 40 years have not had any impact on the child sex ratio," Home Secretary GK Pillai said when the census report was released.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh described female foeticide and infanticide as a "national shame" and called for a "crusade" to save girl babies.

But Sabu George, India's best-known campaigner on the issue, says the government has so far shown little determination to stop the practices.

Campaigners say India's strategy to protect female babies is not working

Until 30 years ago, he says, India's sex ratio was "reasonable". Then in 1974, Delhi's prestigious All India Institute of Medical Sciences came out with a study which said sex-determination tests were a boon for Indian women.

It said they no longer needed to produce endless children to have the right number of sons, and it encouraged the determination and elimination of female foetuses as an effective tool of population control.

"By late 80s, every newspaper in Delhi was advertising for ultrasound sex determination," said Mr George.

"Clinics from Punjab were boasting that they had 10 years' experience in eliminating girl children and inviting parents to come to them."

In 1994, the Pre-Natal Determination Test (PNDT) Act outlawed sex-selective abortion. In 2004, it was amended to include gender selection even at the pre-conception stage.

Abortion is generally legal up to 12 weeks' gestation. Sex can be determined by a scan from about 14 weeks.

"What is needed is a strict implementation of the law," says Varsha Joshi, director of census operations for Delhi. "I find there's absolutely no will on the part of the government to stop this."

Today, there are 40,000 registered ultrasound clinics in the country, and many more exist without any record.

'Really sad'

Ms Joshi, a former district commissioner of south-west Delhi, says there are dozens of ultrasound clinics in the area. It has the worst child sex ratio in the capital - 836 girls under seven for every 1,000 boys.

Delhi's overall ratio is not much better at 866 girls under seven for every 1,000 boys.

"It's really sad. We are the capital of the country and we have such a poor ratio," Ms Joshi says.

The south-west district shares its boundary with Punjab and Haryana, the two Indian states with the worst sex ratios.

Since the last census, Punjab and Haryana have shown a slight improvement. But Delhi has registered a decline.

"Something's really wrong here and something has to be done to put things right," Ms Joshi says.

Almost all the ultrasound clinics in the area have the mandatory board outside, proclaiming that they do not carry out illegal sex-determination tests.

But the women in Sagarpur say most people here know where to go when they need an ultrasound or an abortion.

They say anyone who wants to get a foetal ultrasound done, gets it done. In the five-star clinics of south Delhi it costs 10,000-plus rupees ($222; £135), In the remote peripheral areas of Delhi's border, it costs a few hundred rupees.

Similarly, the costs vary for those wanting an illegal abortion.

Delhi is not alone in its anti-girl bias. Sex ratios have declined in 17 states in the past decade, with the biggest falls registered in Jammu and Kashmir.

Ms Joshi says most offenders are members of the growing middle-class and affluent Indians - they are aware that the technology exists and have the means to pay to find out the sex of their baby and abort if they choose.

"We have to take effective steps to control the promotion of sex determination by the medical community. And file cases against doctors who do it," Mr George says.

"Otherwise by 2021, we are frightened to think what it will be like."

- Published23 May 2011

- Published23 May 2011

- Published23 May 2011