Is communism dead in India?

- Published

- comments

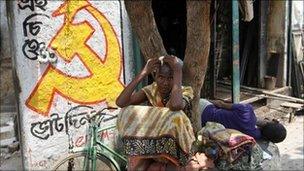

The communists lost the trust of the Bengal voters

Did the communists in West Bengal expect the drubbing they received on Friday at the hands of the upstart Trinamool Congress?

In the gloomy headquarters of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), external in Calcutta, the usually convivial apparatchik, Biman Basu, glumly tells us that the results were "totally unexpected". A collective gasp goes up in the room. A slew of opinion polls, exit polls and reportage had all predicted the rout. But, no, the communists and their allies had not expected it.

So what went so horribly wrong leading to such a debacle for a party which had ruled the state for 34 years, external without a break, and prided itself on reading the pulse of the people like no other party? "The opposition slogan for ushering in parivartan [change] was endorsed by the people. We didn't understand that," Mr Basu says. So are the communists out of touch with the people? "We have grassroots connection with people, but people didn't open their mouths, and we couldn't assess their stirrings for a change," he says.

Does that mean India's communists are losing their touch - with the people, and the fast changing world around them? Have people stopped believing them?

It does appear so. A few months ago, the communists announced two big ticket schemes they promised to implement if were voted to power - cheap rice at two rupees a kilogram for families earning up to 10,000 rupees a month, and free medical insurance for the poor. In many states such welfare schemes, which critics call populist, would have easily fetched votes for the party behind them. No such luck for the communists in Bengal - people simply refused to believe that they could deliver on promises.

Which, many say, is a little tragic in a state where the communists had a few standout achievements after they were swept into power in 1977. The party carried out far-reaching land reforms, ushered in local democracy through village councils and gave the peasants and working class some dignity. There was a sharp decline in poverty and a perceptible rise in living standards of a very politically conscious people. Nobody can take away the credit from the communists here.

Somewhere down the line in a fast-changing world the communists, many believe, began losing their way. After the first wave of farm reforms had exhausted its potential, they needed fresh ideas as governments cut back on spending, and private capital was touted as the main driver of growth and jobs. Land reform had run its course in Bengal, and farm produce prices were falling. Peasants, with enough food in their bellies, now aspired to better lives.

But a largely gerontocratic and hidebound leadership - already stunned into stasis by the break-up of the Soviet Union - "lost its way coping with the pressures of a globalised market", says social scientist Dwaipayan Bhattacharyya.

He continues: "With the growing influences of market forces in the national economy and heightened competition between states to attract private capital, the communists found it increasingly difficult to match its anti-corporate, anti-globalisation rhetoric with the practice of competitive federalism."

So in the past few years, the communist government stumbled and fell flat on its face trying to push through a chemical hub and a car factory by acquiring farming land, external and antagonising the same peasantry which it had empowered by giving them land.

Then there was the party's stranglehold on the people. In what many call a Stalinist streak, Bengal became what Dwaipayan Bhattacharya says was a "party-society". To put it simply, politics in Bengal did not revolve around solidarities based on caste, religion, language or ethnicity. It instead lay in the communist party, which mediated everything you did in your personal and work life, "often transgressing the lines of separation between private and public, civic and political, social and familial".

I remember visiting villages in Bengal in the 1990s where people who had voted for the opposition had been virtually "excommunicated" and deprived of the many benefits that came with being a party supporter.

The decline of the communists possibly means that the "party-society" is now unravelling, and politics in Bengal is entering a new phase. Mamata Banerjee's Trinamool Congress, external which has defeated the communists is largely a regional party, tapping into Bengali nationalism, and seeking to restore the bruised Bengalis' pride and identity.

Identity politics is also now making inroads in Bengal with local parties - like the Gorkha parties demanding a separate state in Darjeeling in eastern India - seeking to address local aspirations. "A one-party-meets-all-aspirations" has become a political anachronism in India, and Bengal may be going the same way.

So does the defeat of the communist party in Bengal and Kerala, their showcase states, mean that communism has lapsed into irrelevance in India? Hardly. Functioning in a democracy, the Communist Party has increasingly resembled social democrats with Stalinist tendencies when it came to forging the party together and packing key institutions with its cadres.

And as I wrote in a previous piece, Ms Banerjee of the Trinamool Congress has basically usurped the communist space with similar rhetoric. "I am not against Communism," she is believed to have said, "but I am against the Communist Party."

With their reserves of dedicated cadres, the communists may well bounce back. But, as Bengal shows, they can no longer take voters for granted. And with mainline Indian parties trying to clothe policy in egalitarian ethics to appeal to the poor majority, the communists have very little new to offer. So will this rout force India's communists to reinvent themselves?, external Going by history, the prospects of them doing so are slim.