John Simpson: Afghanistan, its future, and why China matters

- Published

Face off: Taliban fighters and Pakistani soldiers guard the busy Torkham border crossing side by side

The Khyber Pass is one of the world's great invasion routes - forbidding, steep and treacherous, stretching from the Afghan border to the Valley of Peshawar, 20 miles (32 km) below, in Afghanistan.

For three thousand years, armies have struggled through these rocky defiles and camped in its valleys. You can still see the insignia of regiments from the British and British Indian armies, which continue to be carefully maintained, along the sides of the road, overlooked by the forts they once built and guarded. From the rocks above, Pashtun tribesmen armed with ancient jezails, or flintlock rifles, would snipe at passing soldiers with amazing accuracy.

Nowadays trucks laden with agricultural produce from Afghanistan labour round the sharp bends, sometimes with men and boys clinging to the side of them for the ride. On the pathways beside the road, old men trudge along, bent double under boxes of smuggled goods.

'An atmosphere of fear and urgency'

The Khyber Pass ends at Torkham - Afghanistan's busiest border crossing with Pakistan.

Several years ago the Pakistani authorities completely revamped it. Now the crowds waiting there are better marshalled than they used to be, but there's an atmosphere of fear and urgency as people try to escape from Afghanistan's new rulers, the Taliban. You can see them from the Pakistani side, crowding together behind the wire in the midday heat, waving their documents and begging to be allowed through. For the most part, only people who have permission to leave Afghanistan on medical grounds can cross, together with their families.

The long line, cluttered with wheelchairs and suitcases, shuffles slowly forward through the various checkpoints.

Taliban and Pakistani guards may work relatively peacefully at the border - but they are not friends

On the road, where the actual border runs, a couple of Pakistani soldiers stand face to face with Taliban guards wearing makeshift uniforms.

The Taliban had no objection to talking to me. I asked one of them, a big man with a bushy beard covered by a face-mask, why the national green and red flag of Afghanistan wasn't flying over the border post. It has been replaced by the white flag of the Taliban, inscribed with the Shahada, the basic statement of the Muslim faith: "There is no god but God, and Muhammad is His messenger."

"Our country is now an Islamic Caliphate," the border guard answered proudly, "and this is the correct flag for the whole country."

There are occasional moments of tension, but for the most part the Pakistani and Taliban border guards face each other without hostility.

There is no question of fraternising, though. Many Afghans blame Pakistan for the Taliban's success. They believe implicitly that the militants were founded and promoted by Pakistan, and especially by the ISI, its notorious spy agency. In fact Pakistan's relations with the Taliban have not been nearly as close since Imran Khan became Pakistan's prime minister in 2018, and its influence over the Taliban has been noticeably on the decline.

John Simpson and his team interview a Taliban border guard

The power of China

To most governments, a relationship with the Taliban is distinctly embarrassing right now. The militant group has links with Saudi Arabia and some Gulf states, though not close ones.

The country which has the closest relationship with the Taliban is China, which doesn't show the slightest sign of embarrassment at all. With so many ordinary Afghans trying to flee their country, its economy seems certain to crash, as it did when the Taliban were last in power, from 1996 to 2001. Therefore, Chinese economic support will be needed to keep Afghanistan afloat, and that will give Beijing a sizeable degree of control over Taliban policy.

We can also be pretty certain that the Taliban won't challenge China on awkward issues like the treatment of its Muslim and Uighur population.

The Taliban take-over of power has been disastrous for the United States, Britain, Germany, France and other countries which have helped Afghanistan over the past 20 years. It has also brought India's policy to a dead halt. India injected large amounts of money and expertise into Afghanistan, and had a good deal of influence with the governments of Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani - both of whom wanted India as a counter-balance to Pakistan. That is all finished now.

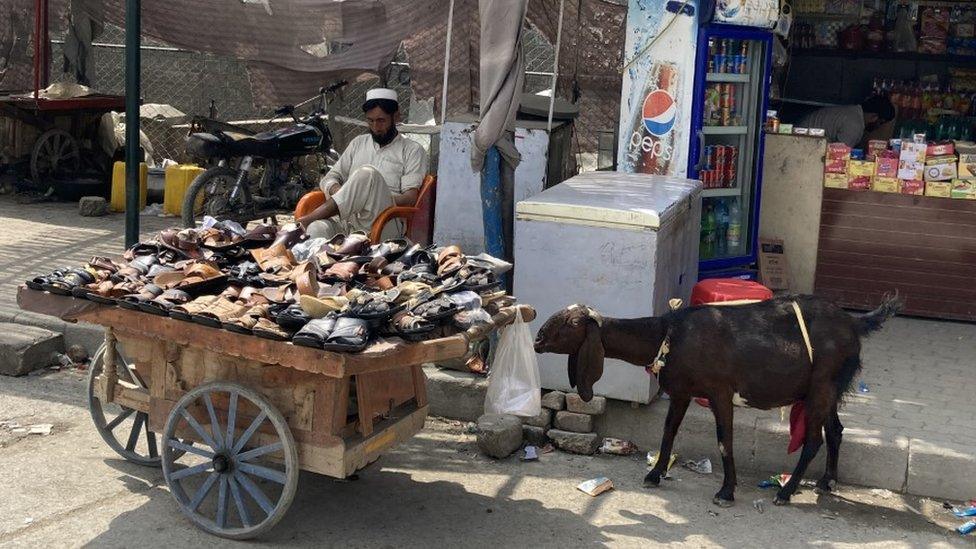

A shop at Torkham in Pakistan, the busiest crossing with Afghanistan

Last time they were in control, the Taliban were treated as international pariahs. The economy got so bad that by 2001 there was no money to buy fuel. The few cars that were left were forced off the road. Most people couldn't afford generators, and power cuts were widespread. The streets were dark and silent at night, and in the daytime most people preferred to stay indoors as much as they could, fearful of the gangs of Taliban vigilantes.

Will it be the same now?

The difference is China. If Beijing decides that it will gain sufficient economic and political advantage, it will save the Taliban from going under. If not, they'll be on their own.

You may be interested in watching:

Taliban parade military equipment through the streets of Kandahar

- Published12 August 2022

- Published29 August 2021

- Published8 September 2021

- Published10 September 2021

- Published7 September 2021