The place where crazy inventors create your future

- Published

Is a home computer in the shape of a desk lamp the future of computing?

More and more of our waking hours are spent in spaces sprinkled with electronic devices - a digital camera here, an electronic book reader there and smart phones as far as the eye can see. But what part did the famous Massachusetts Institute of Technology play?

Welcome to MIT's Media Lab - an academic institution that looks for a breed of student who is one part engineer, two parts futurist and three parts tech-savvy brainiac.

The programme has just celebrated its 25th anniversary by drawing together its alumni and others, including Google CEO Eric Schmidt, to MIT to partake in a day chock-full of techno nerd-oriented talks and an open house featuring the students' research projects.

Walk through the hallways of the elite Cambridge institution any day of the week, and one will see students with thick-rimmed glasses scampering past with stacks of paper containing advanced algorithms, meshes of wires attached to robotic heads, the beginnings of self-propelled prosthetic limbs or even blueprints for the first fleet of foldable cars.

The Media Lab has been behind both technological breakthroughs and social campaigns - the electronic ink used in the Amazon Kindle and Sony e-Reader, the educational programming language Scratch, the One Laptop Per Child initiative and even video games Guitar Hero and Rock Band.

Much of the lab's funding comes from roughly 80 corporate sponsors - though those companies are not allowed to support or direct any of the research.

The lab is divided into 23 research groups, including the eyebrow-raising Lifelong Kindergarten and Opera of the Future, which is aimed at revamping musical theatre using robots, among them. They sit alongside more easily digested group concepts, like Biomechatronics and Synthetic Neurobiology.

Electronic wallpaper created at the lab can turn on a lamp, play music or control appliances.

The lab focuses on the ways technology can impact on us at a human level, says programme director, Frank Moss.

"That might mean how we entertain ourselves, how we take care of our health, our finances, how we live, how we socialize, work and play."

And Mr Moss says innovation at the lab is achieved by taking the students, who he calls natural "builders", and teaching them how to "make almost anything" - which is also the name of a six-month class students at the Media Lab take during their first year, How to Make (Almost) Anything.

"By the time they are halfway through their first year, they can build any piece of software, any circuit board, they can use the laser cutter and build any kind of object out of metal or aluminium, foam, wood, you name it."

'Crazy' students

The idea for the Media Lab was conceived in 1980, and it opened its doors five years later under the direction of Greek-American architect and technologist Nicholas Negroponte and Jerome Wiesner, former MIT president and science adviser to President John F Kennedy.

Mr Negroponte, 66, brother of former US Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte, describes the Media Lab's inception as having had "perfect timing". When it opened the PC had recently been developed, telecommunications would soon be deregulated and the internet was just beginning to stretch its legs as a medium.

Mr Negroponte says a person strolling through the doors of the Media Lab in its infant stage would have been quickly encircled by a maze of computer-controlled balloons, holograms and faculty who had been exiled from other departments - what he calls the "real Salon des Refuses", alluding to French 19th century painters whose work was rejected by the establishment of the day.

And although the programme - now bursting with research projects focused on autism, prosthetic limbs, robots and, well, robotic opera singers - is now getting the attention it deserves, Mr Negroponte says it still attracts like-minded individuals.

"If you are considered crazy in your field, you come to the MIT Media Lab," he says of the students today.

"After about 15 years, it morphed into a style of thought, a way of doing research and into a program that was friendly to risk," Mr Negroponte added.

And the themes of risk and creativity are obvious when looking at some of the projects on display during the programme's open house.

Medical Mirror

The Medical Mirror is a project being developed to allow individuals to check their pulse, respiration and heart rate simply by looking at their own reflection.

The prototype of the mirror can already gauge a person's pulse and respiration

Electrical and medical engineering student Ming-Zher Poh implanted a simple web camera into a two-way mirror, which tracks a person's face when he or she peers into the rectangular looking glass.

The camera then analyses the slightest variations in brightness in the person's complexion caused by blood flow from blood vessels and returns figures on what it calculates.

"People look at the mirror everyday, and people pay attention to their outward appearance - but this [Medical Mirror] also reminds them about their physiological information," he adds.

The Cornucopia

Marcelo Coelho and Amit Zoran of the school's Fluid Interfaces group may have also created a product that could one day aid in personal health - a personal, automatic food factory.

Mr Coelho says the Cornucopia is only intended to replace the duller aspects of preparing a meal

Armed with clear tubes containing an array of ingredients, the Cornucopia is a food printer of sorts that mixes elements of a dish together to produce starters, main courses and desserts.

The current Cornucopia prototype can produce a programmable snack from tubes of chocolate and nuts.

Mr Coelho says the machine offers up the potential for a better understanding of what ingredients go into your food and how healthy the foods you put into your body are.

BiDi Screen

Let's be honest for a moment - is it or is it not starting to seem just slightly archaic to use a remote control, a video game controller or even a mouse to manipulate objects on a monitor or television screen?

The BiDi screen can capture both touch and gestures in front of the display

Professor Henry Holtzman and student Matthew Hirsch in the Information Ecology group at the Media Lab have been working in collaboration with the Camera Culture group on a screen that allows you to control objects on a screen using only your hands.

The bi-directional display interface (BiDi) uses embedded optical sensors to capture both touch and hand gestures in front of a screen.

Mr Hirsch says the technology could be helpful in a range of areas but particularly with gadgets like mobile touch-screen mobile phones, on which displays can sometimes appear cramped.

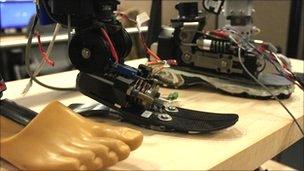

Powered ankle-foot prosthesis

Hugh Herr and his students in the Biomechatronics group have developed a prosthetic ankle capable of propelling a person wearing the device forward in the same way a biological one would.

The Ankle-Foot Prosthesis uses an electric motor to help propel the wearer of the device

The prosthesis uses strings that work like tendons and an electric motor to push the wearer forward and vary the ankle's stiffness, which could help individuals move over varying terrains.

Student Michael Eisenberg says conventional prosthetic limbs, which typically use a passive springs, can make an amputee exert significantly more energy and even cause back problems in the person wearing the ankle.

"Some of the more recent prostheses [on the market] can be in a sense quasi-passive, in that they can move around but cannot provide active energy to the wearer. But it turns out especially in the ankle - that functionality is not sufficient. The ankle is responsible for much more functionality than just that," Mr Eisenberg says.

The Future

Frank Moss feels that during the next 25 years, as Media Lab continues to grow, the public may be hearing more from students like Mr Eisenberg.

"I think we'll see it [technology] around health, around aging, around how we can better control and make decisions in our lives that are in our best long-term interests - it's a level of empowerment that goes beyond shopping, searching, and socializing, to really a deeper agency," Mr Moss says.

And Mr Negroponte says we may even witness significant changes as soon as 10 years from now.

"Every surface will be a display. Everything will be linked to every other thing. Things will know where they are and some may know who they are," he says.

If Mr Negroponte's prediction that technology could soon be conscious of itself proves to be true, it raises one very peculiar but important question: Is the world ready for an opera-singing robot with attitude?

- Published21 September 2010