US children cope with parents behind bars

- Published

This Christmas, more children in America than ever before will have a parent behind bars. The BBC's Zoe Conway visits a women's prison near Baltimore in Maryland to find out how one family is coping with the separation.

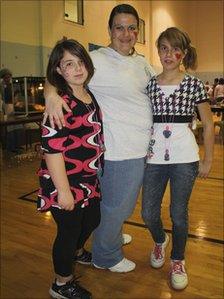

It is family day at Jessup Correctional Institution and the gym is full of women dressed in grey prison uniforms.

They are sitting at tables nervously awaiting the arrival of their children.

Among them is 27-year-old Latasha Shelton, who cannot stay still and keeps looking up at the windows to see any sign of her six-year-old daughter.

"I'm so excited," she says.

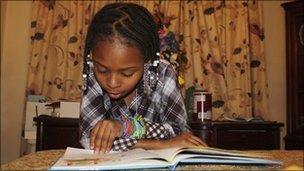

Quite Shelton - her first name pronounced "Cutie" - is dressed in a tartan dress and has beads in her hair.

She runs the entire length of the gym to reach her mother.

Ms Shelton scoops her daughter up and swings her round in the air, while Quite squeals with delight. Once settled on her mother's lap, Quite sings to her.

But Quite has not just come to visit her mother. Her grandmother, Starletta, is also serving time at Jessup, where the two women share a cell.

Drug connection

Ms Shelton and her mother were found guilty of attempted robbery three-and-a-half years ago.

Studies show one in 28 children in the US has a parent behind bars

Starletta was addicted to crack cocaine at the time and tried to steal an elderly woman's purse from a shopping cart.

Latasha was also in the store at the time. She panicked and drove her mother away. Although neither was armed, they each got nine-year prison sentences.

"My drug addiction played a big part in me being incarcerated," says Starletta.

"A lot of women that's in here are addicted to drugs - they suffer from depression. I think that they should get help instead of being incarcerated," she adds.

"When they go home, they are gonna commit the same crime over again - and they just keep coming back. Recidivism, that's what they call it."

Despite the fact that African Americans make up only 30% of the population of Maryland, the overwhelming majority of women at Jessup are black - and so, as is the case nationally, it is black children that suffer most from America's incarceration rate.

One in nine African-American children now has a parent behind bars.

Racial imbalances

America's incarceration rate has quadrupled since 1970, making it five times the level in Britain and 12 times that of Japan.

Becky Pettit, who recently co-authored a study on the impact of incarceration on families, external and economic mobility, says that there is no single explanation for why some groups have higher incarceration rates than others.

But her study, published by the Pew Charitable Trust, indicates racial imbalances are exacerbated by incarceration: more than 35% of all African-American high school drop-outs aged 20 to 34 have served some form of criminal sentence, but that applies to less than 13% of white high school drop-outs in the same age range.

"Sentencing and prosecution politics have contributed to the rise in incarceration rates. And there's a close link between incarceration and social inequality," says Ms Pettit, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Washington.

These trends have been intensified by the disproportionate impact of the "war on drugs", in which three-quarters of those in prison for drug offences are ethnic minorities, according to the Sentencing Project, an advocacy group, external.

Many states have mandatory minimum sentences, which remove judges' discretion to show mercy.

"Three strikes" laws, which were first introduced to lock-up violent repeat offenders for life, have, in several states, been applied to petty criminals.

The war on drugs has often led to harsh sentences not just for dealing illegal drugs, but also for selling prescription drugs illegally.

At the Jessup prison Christmas party, Alfreda Robinson helps hand out presents to the children.

Ms Robinson, who runs the National Women's Prison Project, is worried about the long-term effect the prison sentences are having on the children.

"We've got an angry group of kids - growing up not knowing how to deal with their displaced feelings," she says.

"We've got kids bottling everything up and not talking about it. They're gonna be our adults, and they're gonna explode one day if we don't begin to get them the help they need."

Lasting effects

As Quite sits on her mother's lap and gets her face painted by one of the prison volunteers, she doesn't look like a troubled child, but it is hard to believe that her upbringing will not leave a scar.

Not only has she been separated from her mother and grandmother for more than three years, but she has also lost her father.

He was a Baltimore drug dealer who was imprisoned and then murdered.

One in 100 American adults are now in prison in the US

Without parents to watch over her, it is left to a godmother and Quite's widowed 76-year-old great-grandfather, James Jones, to take care of her.

Mr Jones also looks after three of Starletta's children and appears overwhelmed at his cramped East Baltimore home.

"It takes a toll," he says.

He thinks Quite is smart and that gives him hope. But he admits there are times when she and the other children struggle.

"The younger ones understand their mother's away, they know she did something wrong but they don't fully understand why," Mr Jones says.

"They lash out and there are times when they're really hurting."

At Jessup prison, the children are saying their goodbyes after three precious hours spent with their mothers.

Quite is struggling out the door with a gift bag almost as big as she is.

A moment later, she appears at a window and, with a big grin on her face, she waves to her mother.

Latasha joins the other women to get ready for a strip search.

By the time they get back to their cells, many will be in tears, a prison officer says.

- Published5 July 2010