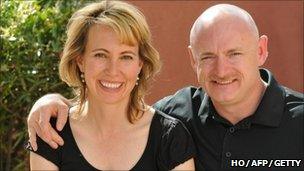

How did Gabrielle Giffords survive a shot in the head?

- Published

Two-thirds of people shot in the head never make it to hospital

Very few people survive being shot in the head at close range, but all indications are that Gabrielle Giffords is one of the lucky few.

Doctors are cautiously optimistic about her condition, but are reluctant to speculate on her recovery.

The swift response of people on the scene - emergency workers and medical staff - has been credited with saving her life in the first instance.

Daniel Hernandez, an intern on her staff, is being called a hero after he rushed to her aid - and closer to the gunman - moments after the shooting.

He applied pressure to the entry wound to staunch the bleeding, pulling her on to his lap so she would not choke on her own blood.

Paramedics then took her to a nearby hospital where trauma surgeon Peter Rhee, a former military doctor who served in Afghanistan, and his team worked with impressive efficiency.

Ms Giffords was in the operating theatre about 38 minutes after she was shot.

The bullet entered at the back of her skull and exited at the front, travelling through the left side of her brain - which controls speech among other things.

Beating the odds

Dr Rhee told reporters that Ms Giffords was fortunate that the bullet had stayed on one side and had not hit areas of the brain that are almost always fatal. Surgeons also did not have to remove much dead brain tissue, another positive sign.

The swift actions of Dr Lemole, Dr Rhee and others helped save Ms Giffords' life

Bone fragments can often travel through the brain with the bullet, causing additional bleeding and damage.

Dr Richard Besser, ABC News' medical editor, said: "She has already beat a lot of odds. Two-thirds of people who are shot in the head never make it to the hospital."

One major concern for Ms Giffords' medical team now is the possibility that her brain will swell.

Neurosurgeon Dr Michael Lemole has removed half of her skull to give the tissue room. The bone is being preserved at a cold temperature and can be reattached when the swelling subsides.

That technique has been used commonly in military injuries, according to Dr Rhee.

Swelling can take several days to peak, and may take more than a week to go down.

Ms Giffords is currently heavily sedated in a coma-like state that helps rest her brain. That requires the assistance of a ventilator, which means she cannot talk.

Doctors have woken her periodically and say she is responding to simple commands like squeezing somebody's hand.

But her medical team is deeply hesitant to speculate on her long-term condition. Dr Lemole said her recovery could take months or even years.

Brain injuries are unpredictable, in part because each individual's neural pathways operate differently.

"The same injury in me and you could have different effects," University of Maryland neurologist Dr Bizhan Aarabi told the Associated Press news agency.