Republican divisions on display at conservative summit

- Published

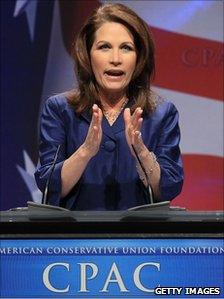

Representative Michele Bachmann called for unity in her CPAC address

Republicans are swarming over Washington DC's Marriott Wardman Park hotel this week, as their biggest annual convention gets under way - the Conservative Political Action Conference, or CPAC.

Conservative activists gather at CPAC to cheer potential 2012 presidential contenders, rub shoulders with rising stars and wander through a carnivalesque convention hall where stall-holders peddle merchandise and promote books, candidates and causes.

Since its humble inaugural meeting in 1973, CPAC has grown exponentially in both attendance and media coverage.

These days, it is almost a necessary pit-stop on the campaign circuit for Republican White House aspirants.

And in the lead-up to presidential contests, throngs of reporters attend, hoping to catch an early glimpse of how candidates' messages resonate with this key block of primary voters and campaign activists.

They are key because CPAC attendees are generally the sort of people who will pound the pavement, burn up telephone lines and donate hard-earned cash to support their preferred presidential hopeful.

In some ways this year will be no different. The focus will be on the numerous possible 2012 contenders who will address the conference - Mitt Romney, Tim Pawlenty, Michele Bachmann, Newt Gingrich and Haley Barbour among them.

The buzz about the next wave of Republican leaders will also mount. Chris Christie, Marco Rubio, Allen West and Kristi Noem are emerging as hotshots to watch.

But this year, what's happening off the main stage may be more revealing about the state of the Republican Party - and what it means to be a Republican - heading into 2012.

Bucking the leader

After deeply demoralising elections for Republicans in 2006 and 2008, Washington's chattering classes declared American conservatives lost at sea, and assumed they would be there for a good long while.

Then, in 2010, Republicans surfed a wave of libertarian, small-government discontent back to political relevance and, more importantly, control of the US House of Representatives.

Figurines of President Barack Obama were among the wares being hawked at CPAC

In doing so, Republicans broadened their conservative tent - a tent that had been dominated during the Bush years by social and religious conservatives and national security hawks.

The ranks of fiscal conservatives swelled thanks to the Tea Party movement, and added an even more libertarian bent to the Republican philosophy: less spending, lower taxes, and an increasingly disparaging view of any form of government intervention. Government with a very, very small g.

Now, the newly-energised and emboldened Republican Party seems to be having growing pains, which are playing out at CPAC.

In the days leading up to the conference, the new conservative wing in the House of Representatives flexed its muscles twice, leaving Speaker John Boehner, a card-carrying member of the Republican establishment, looking as though his fledgling hold on his Congress was tentative at best.

On Tuesday, Mr Boehner's attempt to pass an extension of several provisions of the Patriot Act - the post-9/11 security law which many liberals and libertarians believe is an unacceptable infringement on individual freedom - failed, mostly thanks to newly-elected members.

The following day, a group of Republicans rejected Mr Boehner's planned $40bn (£25bn) in budget cuts, saying they simply did not go far enough. Tea Party representatives, among others, wanted $100bn (£62bn) carved from the US budget.

For some, no spending is sacred - not Medicare, not Social Security and certainly not defence, a department whose massive, sprawling budget Republicans have historically fought vigorously to defend.

Not so proud

This delicate congressional power game sets the scene for CPAC, which has had its fair share of controversy already this year.

Numerous conservative organisations and individuals that usually participate in CPAC - including big names like the Heritage Foundation, the American Principles Project and Senator Jim DeMint - have boycotted the meeting over its decision to allow conservative gay group GOProud to be a sponsor.

The boycott's organisers claim that the inclusion of the gay activists runs counter to conservative values.

GOProud counters that it has solid conservative credentials - a demonstrated commitment to fiscal conservatism and a strong desire for a reduced role for government, particularly in the private lives of individuals.

Some bloggers accused Sarah Palin of skipping the conference because of GOProud's sponsorship. But the former Alaska governor, who has never attended CPAC, suggested the opposite to the Christian Broadcasting Network, indicating that she believes it is a good idea for conservatives of all political stripes to join together in debates.

Possible 2012 candidate Mike Huckabee, former governor of Arkansas, is a no-show for the second year in a row. He has suggested that CPAC has become too libertarian at the expense of its social values.

Too Republican?

The Tea Party Express, one of the largest groups of Tea Party supporters, will not be at CPAC either, after attending last year.

Many Tea Party supporters are conflicted about their relationship with the Republican Party

Even though the movement fielded numerous Republican candidates in 2010, the Tea Party Express doesn't like to define itself as Republican, preferring to keep its distance. Its leadership has deemed CPAC "too Republican".

Elsewhere, some conservative bloggers railed against the inclusion of a panel on faith and religious liberty sponsored by a group called Muslims for America.

Some conservatives continue to harbour a post-9/11 mentality that is deeply suspicion of Muslims.

American Republicans have long enjoyed invoking the "three legs" of the Republican "stool" - social, fiscal and national security conservatism - as a way of describing the breadth of their party.

But as the party grows, those three agendas are becoming awkwardly fractured, sharing less common ground and, in cases like GOProud and defence spending, finding themselves on opposing sides of political debates.

How presidential contenders navigate these fissures - particularly, the growing friction between social and fiscal conservatives - could foreshadow the shape of the race in 2012.

- Published23 November 2010

- Published3 November 2010

- Published16 September 2010